The Archaeological Mission in Somaliland

The Spanish Archaeological Mission in Somaliland

I. Introduction

Historically, the archaeology of the Somali region has faced two main challenges that have hindered its development, in contrast with the Ethiopian Highlands where archaeology was already consolidated as a discipline as early as in the 1920s (Torres 2018). The first one is the colonial partition of this territory into five different entities, each of them developing distinctive control, which led to equally different research traditions published in four main languages (French, Italian, English and German). For decades, the scientific fragmentation of the Horn of Africa paralleled its lack of political integration, without cross-border or collaborative projects to integrate the information that has progressively increased over time. The second challenge is the political instability that recurrently affects the region: successive crises—especially after the collapse of the Somali Democratic Republic in 1991—have discouraged long-term investigations, destroyed incipient research institutions, and limited the dissemination of the results of those projects conducted in the region. The result is the perception of the archaeology of the Somali region as a disconnected series of short-lived initiatives that could be gathered, but not integrated in a coherent narrative. In a recent article (Torres 2018), I have partially contested this perception by providing a joint analysis of the history of the Archaeology of Somalia and Somaliland. The objective was to challenge the idea of a non-existent Somali archaeology, but also to underscore the positive transformations that are taking place in the Somali region (Torres 2018: 294-300). These positive changes are especially visible in Somaliland, a territory that became independent in 1991 and, despite its lack of recognition, has enjoyed remarkable stability since then. This article presents an overview of the Incipit-CSIC archaeological project, the longest initiative of this type ever launched in Somaliland. It situates it within the history of research in the region, and then summarizes its main achievements over these last seven years. It also outlines the project’s contributions to some of the key themes in the historiography of the region, opening debates about topics widely recognized as fundamental, but where data has usually been scarce. Finally, the paper analyzes the future of the project as a tool to build supranational approaches to knowledge, from the perspective of both linking ongoing research projects and acting as a bridge for local institutions in Ethiopia, Somaliland/Somalia, and Djibouti.

II. The History of Archaeological Research in Somaliland

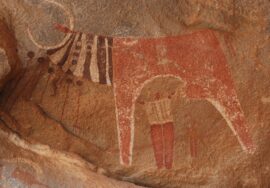

The first references to archaeological remains in Somaliland are as old as the first trip of a European traveler throughout the region: Richard Burton described with some detail medieval settlements during his 1854 trip from Zeila to Harar (Burton 1894: 92-93). Later travelers (Revoil 1882) identified important coastal sites and gathered important collections of lithic tools that would set the foundations for Late Stone Age (LSA) studies in the region (Clark 1954: 22–23). This incipient research was disturbed by the rebellion of Sayyid Muhammad ‘Abdille Hassan, and only in the mid-1920s were investigations resumed and the bases for a scientific archaeology were properly established. Two important works were published in the following decades. The first one was the surveys of A.T. Curle on the medieval towns of western Somaliland (1937) in the context of the British–Ethiopian Boundary commission, which was delimiting the border between both territories. The second one was the book “The Prehistoric Cultures of the Horn of Africa,” by J. D. Clark (1954). He combined his own excavations and surveys with the study of the previous collections and presented the only synthesis of the earlier stages of the prehistory of the Horn of Africa, including a chapter on rock art, which had been documented in the region for the first time (Burkitt and Glover 1946). After the independence and the Union with the Italian Somalia, research was halted in Somaliland. Only in the early 1970s was research resumed, consisting mostly of brief expeditions which identified important archaeological sites, but didn’t evolve into proper research (Warsame, Nikiforov, and Galkin 1974, Chittick 1976, 1979). In general, these trips focused on the region around Mogadishu and the important site of Ras Hafun; Somaliland was visited only episodically. This situation changed in the 1980s, a period that saw a boost in the archaeology of Somalia with the beginning of the first long-term archaeological projects in the country. One of these projects—directed by Steven Brandt between 1980 and 1982—was based in north-eastern Somaliland and combined a revision of sites described by Clark with new surveys in the area between Las Khoreh and Erigavo (Brandt, Brook, and Gresham 1984, 8). During this project, three sites were excavated and the first systematic series of radiocarbon dates in the country was obtained (Brandt, Brook, and Gresham 1984, 15–16; Brandt and Brook 1984, 10). The important rock art paintings of Karin Hegaan published by Clark (1954, 303) were thoroughly documented (Brandt and Carder 1987). Despite these promising results, the next projects of Steve Brandt would be to the south, either in the Buur Heybe Inselberg or in the Jubba Valley (Torres 2018: 280-281). Like in the 1970s, most of the archaeological research took place in the south of Somalia, and, besides Brandt, only two other archaeologists worked in the region in the eighties. The first one was Neville Chittick, who, shortly before his death, visited Biyo Guure, close to Berbera, briefly (Chittick 1984, 17; Dualeh 1996, 39). The second was Sune Jönsson, who worked in Somalia as the director of the project, run by the Swedish Agency for Research Cooperation with Developing Countries (SAREC), to train local archaeologists and to set up an organization responsible for the supervision and protection of the country’s archaeological heritage (Jönsson 1983: 283, Torres 2018: 282-285). Jönsson’s work included some visits to sites in Somaliland, including Maduuna (Torres 2018: 283-284). Unfortunately, after the mid-80’s, archaeological work disappeared from the territory of Somaliland, and progressively concentrated around Mogadishu and the southern part of the country. It is not clear why this move took place: the increasing insecurity and conflict in the northern regions of Somalia, a turn of research interests, or a combination of factors. The Isaaq genocide, the outbreak of the civil war, the collapse of the Somali state structures, and the final breakdown of Siad Barre’s regime in 1991 made any archaeological research in the region unconceivable for two decades. The slow recovery of archaeology in Somaliland started in 2001, when the French archaeologists and historians François Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar and Bertrand Hirsch briefly visited western Somaliland as part of wider research on Islam in the Horn of Africa (Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch 2011). They undertook several test pits in Zeila; however, the largest boost to archaeology in Somaliland came from the rock art site of Las Geel. Thanks to the information provided by Mohamed Ali Abdi, a member of the Department of Tourism of Somaliland, Xavier Gurtherz of the Paul Valéry University of Toulouse (Gutherz, Cros, and Lesur 2003) studied the area. The study and dissemination of this cluster of shelters during the first decade of the 2000s (Gutherz and Jallot 2011, Gutherz et al. 2014) and the interest they raised worldwide led to a debate about Somaliland’s heritage and the need for proper strategies and structures to preserve and use it as a touristic resource in the country (Torres 2018: 291). This debate led to the establishment of a Department of Archaeology directed by Sada Mire, a UK trained Somali archaeologist, who, since the mid-2000s, has been actively working in media to promote Somaliland’s heritage (Mire 2007) and who published new archaeological sites she discovered with local staff and population (Mire 2008, 2015). As a response to this increased interest, a small museum/storage room was prepared to keep the archaeological materials; an incipient tourism industry started in Somaliland around rock art and Laas Geel, in particular. Despite these efforts and the growing interest of local authorities and many Somalis both in the region and abroad, by 2012, archaeological fieldwork in Somaliland stopped completely due to a combination of factors (Torres 2018: 291). In this context, the Spanish Archaeological Project in Somaliland was launched in 2015.

III. The Incipit Project

A. The Fieldwork

The Incipit-CSIC Archaeological project in Somaliland is was launched in 2014 as a part of a two-leg project aimed to study the characteristics of the international trade at both sides of the Indian Ocean (the second project was based in Mozambique), and, especially, the interactions between local communities and foreign traders in both regions. Given its strategic position at a crossroads between Africa, Arabia, and the Indian Ocean, Somaliland seemed an excellent place to analyze these topics and compare the information gathered with those from Ethio pia, a region where the members of the project had been working since 2002. The first campaign took place in 2015, and since then, archaeological campaigns have been conducted on annual bases. The first field campaign consisted of a short trip to the country to gather first-hand information about Somaliland and evaluate the possibilities of conducting research there. Berbera, Dubar, Zeila, Fardowsa and Qorgab were visited (González- Ruibal et al. 2017) and contacts were established with the local authorities in charge of the Somaliland heritage. The second campaign (2016) combined coastal surveys around the Berbera area (Berbera, Bulhar, Bender Abbas) and work in the interior, documenting a wide range of towns, caravan stations, and nomadic meeting sites (González-Ruibal and Torres 2018). In 2017, research focused on the town of Bulhar, where a four-week excavation was conducted, complemented with surveys near Berbera and Borama (Torres et al 2017). The fourth campaign (2018) focused on two main geographic areas: the coastal sites of Xiis and Maydh in Sanaag region and the area around the village of Boon, to the north of Borama, in the Awdal region. In Xiis, a preliminary survey of this important site was conducted, while in the Borama region five medieval sites were documented (Torres et al 2018). That same year, a short trip was made to the site of Kabab, to the west of Berbera, with participation from some members of the team in the Somali Studies International Association conference held in Hargeisa. The importance of the remains documented in Xiis led to the 2019 launch of a comprehensive campaign of surveys and excavations at the site and its surroundings to more in-depth analysis. Four cairns at Xiis were excavated (Torres et al 2019), the whole area was systematically surveyed, and the neighbouring site of Shalaw was also visited. The town of Maduuna, close to El Afweyn, was also briefly visited on the way back to Hargeisa. Finally, the 2020 campaign focused on the axis between Berbera and Burao and combined a long-term excavation in the medieval town of Fardowsa (Torres et al 2020) with intensive surveys in the area of Berbera (González-Ruibal et al 2021). In Berbera, the sites of Ceel Gerdi, Siyara, and Bandar Abbas were re-visited, and the site of Biyo Gure was documented for the first time. Around Fardowsa (in the village of Sheikh), several other sites like Galoley and Gugux were surveyed and documented. Finally, in the hinterland of Burao, two archaeological sites were also identified (Jirow and Ceel Dheere), being the first sites archaeologically documented in the region. In general, the methodology of the Spanish team has mixed selective surveys combined with small test pits when possible. Only in the later years the increase of available funding has allowed larger excavations in sites like Fardowsa. Given the scant information about the archaeological sites of Somaliland, it was decided to evaluate the potential of known places rather than start intensive surveys from the very beginning. In that sense, the support and help of the staff of the Department of Tourism has been invaluable, especially that of Mr. Abdisallam Mohamed Shabelle and Mr. Mohamed Ali Abdi, who have an extensive knowledge of most of the archaeological sites discovered so far in Somaliland. Mr. Mohamed Ali Abdi specifically, despite not having professional training, has gathered an astonishing amount of data and prepared a number of hand-made maps which have been extremely useful for our research. Their advice and suggestions have been fundamental for the success of the project, and they have played a (not always well) recognized role in the protection of Somaliland’s heritage. In addition, the project has relied on the bibliography available (Curle 1937, Fauvelle-Aymar 2011, Mire 2015) and the excellent cartography made during the British colonial period, which has preserved a significant number of toponyms very useful in finding archaeological sites. There are several reasons for this methodology of documenting many sites instead of focusing on some promising ones. The first one was the need to understand the characteristics and variability of Somaliland archaeological record, which has been scarcely investigated and published. The second one was to approach trade networks from a global perspective, not only at the contact points by the coast, but also inland, where the role of local communities could be better understood. Finally, we consider that a more extensive documentation of sites could benefit their management and preservation, as most of them lacked any prior information about their characteristics and chronology.

B. The Outcomes of the Project

So far, the project has documented 36 main archaeological sites and hundreds of minor archaeological structures, such as isolated cairns. The main sites have been surveyed, mapped, and documented through a combination of topographical techniques, 3D modeling, drone flights, photographs, and GPS referencing. Samples of archaeological materials have been collected during the surveys, usually pottery and glass, but also shells, bones, or charcoals, when possible. In the test pits and larger excavations, an exhaustive collection of archaeological materials and samples was made, along with the documentation of structures and archaeological layers. Special attention was given—when funding was available—to the collection of samples for radiocarbon dating, dramatically absent from Somaliland’s archaeology. Post-processing of materials included the photographing and drawing of thousands of items in what is the first systematic documentation of archaeological objects in Somaliland. When possible, samples were exported for analysis in Spain: usually animal bones, but also pottery fragments, metal objects, and organic materials. The results of this work to this day represent the most consistent archaeological program in the history of all the Somali region, with 36 sites documented, ten sites tested, and one excavated on a larger scale (Figure 3). Most of the sites correspond to the Medieval period, although the project has documented from the Late Stone Age to contemporary sites. About ten thousand archaeological items have been collected, of which about 1,700 have been drawn. Fifteen carbon-14 dates have been obtained, and collections of animal bones, shells, pollen, charcoals, seeds, and other archaeological materials have been collected and stored for future research. In addition to this, an intensive remote-sensing survey of the territory of Somaliland has identified about 70,000 archaeological structures (cairns, mosques, etc.) using tools such as Google Earth, which are providing another perspective— less detailed, but more systematic—on the impressive archaeological heritage of Somaliland. Although much more research is still needed, the information gathered during these years, once fully published, will allow the integration of Somaliland’s archaeology within the wider interpretative frameworks of the Red Sea, Horn of Africa, and Indian Ocean archaeologies.

C. A Collaborative Project

As mentioned above, the collaboration with Somaliland authorities and researchers has been fundamental since the beginning of the project. Members of the Department of Tourism (and since 2018, the Department of Archaeology) have actively participated in the fieldwork and the post-processing of materials, including the publication of scientific results. The Spanish Archaeological project has trained staff from the Departments of Tourism and Archaeology both in archaeological techniques and the inventorying, management, and preservation of archaeological objects and has supported the acquisition of storage equipment as the collections has grown throughout the years. Public lectures and talks at the Ministry of Trade Industry and Tourism have been given on regular basis and full reports of every campaign have been delivered to the Department of Archaeology every year, making sure that all the information collected during the fieldwork remains in Somaliland. The collaboration with Somaliland institutions acquired a new dimension with the construction of the National Museum of Somaliland, the institution that will protect and display the rich archaeological, historical, ethnographic, and artistic heritage of the country. As the future destination of the archaeological collections of Somaliland, the Spanish Archaeological project has shown its commitment to this project and has launched a plan to support the Museum in the training of staff in curation and conservation practices, the acquisition of equipment, and the design of its future exhibition. The launch of the National Museum, expected in 2023, will open a new stage in the relationship between the Incipit-CSIC project and the Somaliland Heritage institutions and will hopefully help to increase the awareness of the Somaliland population about their history and heritage.

IV. The Scientific Themes

As usually happens with scientific projects, the Spanish Archaeological project has evolved throughout the years, expanding its scope and interests. Although the study of trade has remained one of the key themes, other topics have been incorporated or have developed their own research trends. Parallel to this diversification, the Incipit-CSIC project has broadened its geographical scope and, from the original Somaliland-based project, has expanded to approach wider geographical contexts. At this moment, the Spanish Archaeological project in Somaliland is an umbrella term that includes several initiatives and projects, including the ERC Starting Grant StateHorn1 and the project IAPATHA (focused on the study of the trade in the Horn of Africa in the Antiquity). As our knowledge of Somaliland’s archaeological record has increased after each campaign, new research questions have arisen and new relationships with nearby regions have been established.

A. The Antiquity of Somaliland

The study of the connections between the Horn of Africa and the rest of the world during the first millennium BC/AD have historically been a major topic in Somali studies, based on the description of the Periplus of the Eritrean Sea, the main source of information for the 1st century AD Western Indian Ocean trade (Casson, 1989). The Peryplus describes several trading posts along the Somali coast—Avalites, Malaô, Mudu and several others—and the identification of these toponyms with archaeological sites started as early as 1882, when the French traveler Georges Revoil identified Xiis with Mosyllon (Desanges 1993, 28), although the description fits more adequately with that of Mundus (González-Ruibal González-Ruibal et al 2022). In the 1970s, the first comprehensive attempt to document these early trading posts (Chittick 1980) led to the discovery of the important site of Ras Hafun, identified with the Opone of the classical texts, as well as short visits to Daamo and Xiis. Unfortunately, this project was short-lived, and the results of the excavations have never been fully published (Smith and Wright 1988, 1990). Since Chittick’s initiative, sites like Xiis, Ras Hafun, and Daamo have been recurrently included in studies of the Indian Ocean Trade during the Antiquity (Horton 1996, Seland 2014), although no more work has been done on this period besides a short reference to a Sabaic (1st millenium BC) inscription found in Shalaw, about 30 kilometers west of Xiis (Mire 2015, 127). In 2018, the Incipit-CSIC project visited briefly Xiis to evaluate the interest of this archaeological site and assess the possibility of conducting a campaign there. The finding of archaeological materials similar to those found by Georges Revoil in the 19th century (Desanges 1993) and the state of preservation of the structures led to the launch of a much larger campaign in 2019, when the site was fully surveyed and mapped and four cairns were excavated, in what was the first systematic excavation of this type of sites in the history of Somaliland (Torres et al 2019). In addition, all the hinterland of Xiis was also surveyed, which led to the identification of two more archaeological sites in the small island in front of the site and on the top of the Majilin Hill. To the north of the site, more than two hundred cairns and other funerary structures were documented, raising the total number of tumuli to more than 500. Numerous materials were collected during both the surveys and the excavations, which have provided a chronology of the 1st to the 3rd centuries AD (Fernández et al 2022). Unfortunately, the radiocarbon samples collected didn’t yield any results due to the poor state of preservation of the bones. Finally, a short visit was paid to the nearby village of Shalaw to document the Sabaic inscription and the funerary structures. The survey of the whole area led to the discovery of a second, undisturbed graveyard, likely of the same 1st millennium chronology. The importance of the Xiis results led to the launch of a specific project—IAPATHA—aimed to study the trade in the Horn of Africa in the Antiquity. Unfortunately, the typhoon Pawan, which hit Somaliland later during the winter, prevented a second campaign in Xiis, but research continued, this time in the coast of central Somaliland, where evidence of trade during the first millennium has been found in the site of Ceel Gerdi, some 20 kilometers east of Berbera (González-Ruibal and Torres 2018, 25). The surveys conducted in this area in 2020 led to the discovery of a series of shell middens, some of which had yielded imported pottery and a fragment of glass dated in the mid-1st millennium AD. The origin of these objects is varied, but Axumite items are predominant with some examples of Arabian and Mediterranean wares. Although less spectacular than the objects found at Xiis, the materials found at Ceel Gerdi are key to understand a chronological period—the second half of the 1st millennium AD—which so far had not been identified in Somaliland. During the same campaign, the first inland site with pre-Islamic imported materials was found near Burao. The survey of the cairnfield of Jirow led to the identification of several green glazed pottery fragments similar to those found in Xiis, which could then date the site in the first half of the 1st millennium AD (González Ruibal et al. 2022). The results of the Incipit-CSIC research on the trade in Somaliland during the Antiquity are improving significantly our understanding of the involvement of this region during the 1st millennium AD and the extent, intensity and origin of its contacts with other regions. The excavation of Xiis is providing, for the first time, systematic information about the funerary practices, graveyard organization patterns, and international relationships of the nomadic populations of the first through third centuries AD, while the surveys around Berbera complete the information about the pre-Islamic period of Somaliland. The study of the archaeological materials found in both regions is providing a better insight of the long-distance trade that connected Somaliland with the Mediterranean Sea, the Arabian Peninsula, Middle East and the Ethiopian Highlands. Moreover, the research conducted in Xiis and other sites has begun to shed light on the role of the nomadic societies in the Western Indian Ocean system. Despite being the dominant type of society in the southern shore of the Red Sea and having the control of highly valued resources, nomads have seldom been in the focus of research (González Ruibal et al.2022, 132). The Incipit-CSIC study of nomadic sites and their hinterlands is helping to present a more balanced perception these communities and their participation in one of the key economic activities during the Antiquity.

B. Somaliland and the Western Indian Ocean Trade System During the Medieval Period

As we have seen in the previous section, trade is one of the oldest and most important activities in the Horn of Africa, and has acted as an invaluable tool to integrate and open the region to historical dynamics, cultural and economic changes, and new ideas. The participation of Somaliland in the so-called Western Indian Ocean trade system has always been recognized (Chittick 1980, Horton 1996, Seland 2014), but when the Incipit-CSIC projects were launched in 2015, there were remarkable gaps in our knowledge in most of the practical aspects of this trade. There was an almost total absence of archaeological sites identified as trading places, the study of imported materials was scant and there were very few data about the origins, mechanisms and rhythms of the commercial exchanges. Moreover, there was no information about how local communities engaged in trade, despite being one of the fundamental agents in the control of strategic resources such as frankincense, and the receptors and distributors of imported goods inland. During the six years of work in Somaliland, the Incipit-CSIC project has launched a very ambitious research plan to overcome these difficulties. A significant number of places related to trade activities has been documented both by the coast and inland, and a huge effort has been made to identify and ascribe chronologically the abundant and varied imported materials found in surveys and excavations. What is more important, the ethnographic study of nomadic seasonal displacements and economic strategies has helped to set a realistic interpretation for the sites found in Somaliland. Although more research is arguably needed, the work of the last six years has set a general framework for the commercial strategies, dynamics, and chronologies the region went through in the last two millennia. This information is especially relevant in the case of central Somaliland, where a significant number of trade-oriented archaeological sites have been documented in different campaigns. Regardless of the period and well into the 19th century, trade has always been conducted in Somaliland following the monsoon regime and coordinated nomadic movements. The latter move south from April onwards, concentrated along the coast from October to the beginning of the rains in April (González-Ruibal and Torres 2018, 25-26). This seasonal trading system was already noticed by the early 19th century travelers (Cruttenden 1849, 54-55), and has prevented the emergence of urban centers in Somaliland, contrary to what happened in the East Africa coast. Only Zeila, and to a lesser extent, Berbera and Maydh, seem to have held permanent population, at least until the 16th century. During the end of the 1st millennium, the tradition of open, temporary places for trading detected in Xiis and Ceel Gerdi continued with coastal fairs like Bandar Abbas and Siyaara. These were important sites where nomads met to trade and celebrate social and religious meetings (González-Ruibal 2018: 29-34). It was in Bandar Abbas where the first evidence of contact with Islam could be detected, in a context of ritualized exchanges with people probably coming from the Arabian Peninsula. During the 11th through 14th centuries, materials from Yemen were dominant, but objects from East Asia, India, Persia and Middle East are also documented (González-Ruibal et al 2021: 3).

In a second period (15th-16th centuries), trade saw a sharp increase both in quantity and variety, as can be seen in the samples recovered from sites like Siyaara and Farhad. Yemeni imports diminish, while the number of East Asian wares grows significantly. In general, the predominance of materials from Asia (in contrast to the Mediterranean, Persia, or Middle East) was always overwhelming (González-Ruibal et al 2021, 24). By the 16th century, imports suffered a dramatic decline throughout Somaliland. Materials from the 17th century AD are very scarce and concentrated in few places along the coast. The reasons for this collapse are manifold: the disturbance of trade routes by the Portuguese, the disappearance of the Sultanate of the Adal due to military defeats, and the Oromo migrations. This generalized political instability implied the end of trade at large scale, but the dismantling of a network of permanent settlements that had grown in Somaliland between the 13th and 16th centuries (Torres 2020: 188).

These permanent settlements are characteristic of the medieval period of Somaliland, and are undoubtedly related to the growth and expansion of the trade routes and the increasing role of medieval states across the region. Many of them were situated at strategic mountain passes along the main routes and were actively involved in trade, as has been documented in sites like Fardowsa or Biyo Gure. The excavation of around 600 square meters in Fardowsa has documented two large houses with abundant imports from Asia and Middle East, in what seems the household of wealthy family involved in trade (Torres et al. 2020). In the case of Biyo Gure, about 15 kilometers southeast of Berbera, significant amounts of imported materials have been found in a small village that was destroyed in a violent event in the 16th century (González-Ruibal et al. 2021, 23). Not all the trade-related sites were actually settlements; in 2016, a caravan station following a Middle East design was located in Qalcadda (González-Ruibal et al 2017, 149-152). The buildings, dated by radiocarbon in the 15th-16th centuries, constitute at the same time a testimony of the growing impact of trade in the interior of the nomadic territory and the interest of the Sultanate of Adal in controlling and securing the trade routes across Somaliland (Torres 2020, 183).

As happens with the Antiquity of Somaliland, trade during the medieval period still requires more systematic research in terms of excavations, surveys and analyses that reinforce or nuance the framework provided by the Incipit-CSIC team. Beyond the chronologies and the material evidences of exchanges, the analysis of the trading dynamics in Somaliland is helping to identify the 14th-16th centuries as one of the most important periods in the history of Somaliland. A period that saw dramatic changes such as the development of permanent settle ments in nomadic territory, the beginning of economic inequality, the arrival and consolidation of a new religion—Islam—and the increasing pressure of states from the west. Throughout all these transformations, trade—as the longest and most important collaborative activity in Somaliland—acted as a common ground for different actors and stakeholders, easing interactions and preventing conflicts. It also reinforced the role of the nomads as the only dynamic agent within a network of coastal fairs, towns, and caravan stations (Torres et al. 2022).

C. States and Communities: The Medieval Period in Somaliland

One of the least known aspects of the history and the archaeology of Somaliland is the relationship between this territory with the states that, at least since the 13th century, controlled wide areas of what is now south-eastern Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Somaliland. It is generally assumed that areas of Somaliland were under control of the Sultanate of Adal (1415-1577), and written texts describe how the Somali were progressively involved in the struggle between Adal and the Christian kingdom of Abyssinia. However, there are many doubts about the question of control. That is, if it was direct or through alliances or proxies, what were the material expressions of statehood in Somaliland, and which were the tools for legitimacy and authority used by the sultans of Adal. So far, the only material expression of state control in central Somaliland is the caravan station of Qalcadda, which makes very explicit the interest of Adal on the control of the trade routes that connected the coast with the interior of the Horn of Africa. In 2020, a new project—StateHorn—was launched by the Incipit-CSIC team to investigate the Muslim medieval states in the Horn of Africa, in order to better understand their territorial, political, social, and economic organization.

Regardless of the influence of states, it is clear that Somaliland went through significant social and economic transformations during the medieval period. The most perceptible was the emergence of a network of permanent settlements that dotted western and central Somaliland, in what had previously been nomadic territory (Torres et al 2022). Although these permanent settlements were identified as early as the mid-19th century, and have been the object of recurrent visits and publications (Curle 1937, Huntingford 1978, Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch 2011), little has been made in terms of their proper documentation. A cluster of sites at both sides of the western Ethiopia-Somaliland border was surveyed and described by Alexander T. Curle in the 1930’s, and a number of sites were listed or visited in the region between Berbera, Burao, and Hargeisa. However, before the arrival of the Incipit-CSIC, the archaeological information about these sites was extremely scarce. Since 2015, the Incipit-CSIC team has progressively documented these sites: those in western side of Somaliland were visited in 2015, 2017 and 2018 (González-Ruibal et al 2017, Torres et al 2018), while those in the central part of Somaliland were surveyed in 2016 and 2020 (González Ruibal et al 2017, Torres et al 2020). As a result of these surveys and excavations, a total of 17 medieval settlements have been documented, five of them tested, and a long-term excavation has been launched in Fardowsa (Sheikh) in 2020 (Torres et al 2020).

The results of this work have allowed a better understanding of the organization of these sites, their functionality, and their material culture. Despite significant differences in size—from towns of more than 200 houses to small hamlets—all the settlements share a remarkable spatial and architectural uniformity, regardless of their emplacement, function, or size. The sites do not present a clear urbanism, with the dwellings being typically scattered throughout the area. None of them are walled, in contrast to what happens with most of the Ethiopian settlements of the same chronology. The most important buildings are the mosques, which, in the larger settlements, have some degree of monumentality. The local pottery shows a high degree of uniformity, too, suggesting a shared identity regardless of the region or the characteristics of the site (Torres 2020, 176).

Although the sites are usually described generically as settlements or towns, the research conducted by the Incipit-CSIC has documented a far more varied typology, with some sites being identified as strongholds, religious settlements, or caravan stations. Moreover, only a few of the sites can actually be considered proper tows, such as Fardowsa, Abasa, and Amud. The rest can be considered villages, holding between 5 and 30 houses. Although it has generally been assumed that these settlements were involved in trade, the research of the last years has shown a different, more complex situation. The percentages of imported materials are very low in most of the sites documented so far, and the presence of objects related to agricultural works and crops processing suggest that the economy of many of these settlements was actually based on agriculture (Torres et al 2018, 34). These sites coexisted with other settlements which were undoubtedly involved in long-distance trade, such as the already mentioned cases of Fardowsa, Biyo Gure, and Qalcaada.The research conducted at the medieval settlements of Somaliland is raising a number of key questions about the parameters in which these communities interacted with the nomadic population and with the states that controlled the territory (Torres et al 2022). From the data available, the western settlements could be included in the territory directly controlled by the sultanates of Ifat and Adal. In central Somaliland, the situation is not so clear; the presence of caravan stations and other data point to the influence, but not control, of the state of Adal. In this region, some settlements like Fardowsa seem to have been founded at an earlier period and be deeply involved with trade. Farther to the east it was nomadic territory: eastern Somaliland is described as “the Land of the Somali” (Faqih 2003), and the influence of Adal was minimal and reduced to punitive expeditions. Regardless of their function, location, and size, all the known inland settlements disappear by the end of the 16th century. The reasons are manifold: the defeats of the Sultanate of Adal against the Christians, the Oromo migrations, and the blockage by the Portuguese of the Indian Ocean routes led to a general collapse of the Muslim state and the abandonment of most of these sites, with the exception of Harar. This abandonment has been perfectly documented in the archaeological sites investigated by the Incipit-CSIC team, which has confirmed the violent end of some sites such as Biyo Gure (González-Ruibal et al 2021: 23). In other cases, like Fardowsa, the end seems to have been progressive and peaceful. By the 17th century, the vast majority of the Somali had returned to nomadism, embracing a lifestyle which has lasted until our days.

D. The Archaeology of the Nomads

The majority of the population, until very recently, has been nomadic.

For those urbanized in Somaliland, the nomadic folkways are overwhelmingly recognized and praised. Their material remains—mostly funerary structures—are ever present in the landscape along the wadis, the mountain passes, and the coast. And yet, we know very little about their archaeology, their past materiality, and their interactions with other groups throughout time. The study of the archaeology of the nomads was at the center of the Incipit-CSIC project since its design, but our interpretation of their material evidence has grown, parallel to our understanding of their lifestyle and displacements throughout the territory.

Archaeological studies of the nomads in Somaliland have traditionally been focused on the study of their funerary structures (Chittick 1992, Cros et al 2017, Lewis 1961), very abundant throughout the territory of Somaliland. The Incipit-CSIC team has also documented several hundreds of these structures during its surveys, and a remote sensing survey made through satellite images have documented several thousands more. In addition, other nomadic structures—camel pens, mosques, etc.—have also been registered, offering a much more sophisticated overview of the nomadic occupation of the territory. The main problem of these approaches is to establish a proper chronology for these funerary structures—a challenge that requires a specific attention.

Although the documentation of cairns and other tombs is important, the Incipit-CSIC tried to move forward in order to understand how nomads organized their territory in the past. The identification of a series of archaeological sites in central Somaliland (González-Ruibal and Torres 2018), dated in the medieval period, helped us to propose a model based on nodes of contact in the form of gathering places. These provided a temporal and spatial framework for the population through the recurrent activities—economic, social, and religious activities. We called these nodes of contact interfaces, and made a dis tinction between those that articulated relations between communities with the same cultural background (internal), and those that regulated interactions between nomads and other groups with different cultural parameters—interfaces of exteriority (González-Ruibal and Torres 2018: 24–25). On the coast, the gathering places were the coastal fairs that we know have been running at least since the beginning of the 1st millennium AD. Inland, the gathering places acted as meeting points for different nomadic groups that would meet to trade, exchange news, establish truces or alliances, or arrange marriages. These gathering places seem to have been related to the worship of ancestors, as the two archaeological sites found so far—Iskudar and Ceel Dheere—seem to have been organized around clusters of cairns and other tombs. Excavations at Iskudar have documented evidences of banquets among the tombs, following a long, pre-Islamic tradition that has been documented in other nearby groups like the Afar (Thesiger 19996: 123-127). Interestingly, radiocarbon dating in Iskudar has provided a chronology of the 12th-13th centuries (1101 to 1300), showing the resistance of the nomadic populations to embrace Islam well into the 2nd millennium AD (González Ruibal and Torres 2018, 34-37). The interpretation of nomadic archaeology as a combination of fixed nodes and seasonal displacements has provided a more dynamic framework to understand the history of these communities, challenging the perception of the nomads as an immutable collective. The changes detected in the different archaeological sites—either by the coast or inland—show that the Somali nomads went through a significant number of deep transformations since Antiquity and especially in the 2nd millennium AD. Between the 11th and the 16th centuries, Somaliland nomads saw the arrival, expansion, and consolidation of a new religion (Islam), the emergence of a network of permanent settlements with a radically different materiality, an increase in trade that triggered processes of economic inequality, and the mounting presence of the sultanates to the west. The outcome of these deep transformations could have been widespread conflict. However, there are many hints that suggest that the nomads were able to adapt to these changes, to establish common grounds with other communities and stakeholders, and to keep a remarkable stability throughout the medieval period (Torres 2020, Torres et al 2022).

Our research suggests that this balance was achieved through the development of areas of common interest around which nomads and other communities could meet and work together. One of them was obviously trade, the longest collaborative project in Somaliland, around which different agents reorganized as the trading system grew in sophistication. The second one was Islam, which provided a shared set of beliefs and a materiality recognizable by nomads, sedentary and traders alike (Torres 2020, 183-188). The Sufi Islam that rooted in Somaliland was very efficient in integrating previous beliefs and traditions, and eased the tensions inherent to religious change (Lewis 1956). Combined, these and other “spheres of interest” helped to structure the relationships and interactions of all the communities inhabiting the region, and allowed the nomads not only to endure these changes, but to cooperate and even thrive.

In fact, it’s likely that the importance of nomads increased through time, as the only mobile group connecting the fixed nodes that were towns, coastal fairs, and caravan stations. This adaptability was challenged by the pressure exerted by the Sultanate of Adal in the mid16th century, but the collapse of this state proved the extraordinary resilience and adaptability of the Somali nomads. States disappeared, trade dwindled, and the network of permanent settlements was dismantled, but the nomads adapted to the new situations so successfully that nomadic culture has ultimately been identified as the traditional Somali lifestyle until today (Torres et al 2022). This acknowledgment of the Somali nomads as a community with a long and dynamic history, full of transformations, was one of the main objectives of the Incipit-CSIC since its beginning in 2015. Although far from complete, the research of these past six years has renewed the ways nomadic archaeology is understood in Somaliland.

V. Moving forward: the future of the project

During the past six years of work, the Incipit-CSIC has conducted the first long-term project in Somaliland, gathered a remarkable amount of data, and started to build interpretative frameworks for some of the key historical periods of the region. Future fieldwork and the publication of the information that is still being processed will serve to increase our knowledge, reinforce nuance, or refute current hypotheses. The Incipit-CSIC project has proved to be highly adaptive and flexible in order to integrate new data and interests, and given the incipient state of the archaeology in Somaliland, it is likely that these interests will change in the future. At this moment, one of the objectives of the project is to challenge the fragmentation of the Somali archaeology in the Horn of Africa—one of the main obstacles for a proper understanding of the history of the region. To do so, the effort aims to start projects in nearby countries like Djibouti or Ethiopia, with similar archaeological record, but very different research trajectories. This trans-border approach tries to achieve a more balanced vision of territories that for many centuries shared a common history and still share many cultural traits. It will also require a close relationship with local and national institutions from these different countries, with the Incipit-CSIC research acting as a bridge to facilitate communication and work between local institutions.

This supra-national research will also benefit from the coordination with two other large projects working on similar interests: Becoming Muslim—focused on the archaeological site of Harla and the area around Harar (Insoll 2021, Insoll et al 2017)—and HornEast, a project which analyses the interactions between Christians and Muslims between the Horn of Africa and Middle East. Combined with previous research and other projects throughout the region, our understanding of the history of the eastern and south-eastern areas of the Horn of Africa can go through a real revolution in the next decade. In that sense, and at the same time, recent discoveries like the recently published Saabaic inscriptions from Puntland (Shiettecatte, Prioletta and Robin 2021) show how much work is still ahead and the extraordinary potential of the Somali region to change the ways we conceive the history of the Horn of Africa.

By Jorge de Torres