The Role of Business in Maintaining Peace in Somaliland

The Role of Business in Maintaining Peace in Somaliland

Somaliland has been peaceful for the last four decades, though this peace remains fragile. Analysts have accredited Somaliland’s relative stability to its bottom- up peacebuilding approach. Politicians, elders, business people and religious leaders complement each other to restore and maintain peace in Somaliland’s hybrid governance system. While these actors constantly contest influence and resources, when peace is threatened they have held each other into account, assisted by civil society and the media. In this brief, we ask what the role of local and foreign private sector actors is in maintaining peace and stability in Somaliland. We argue that foreign private actors are important to attract capital, skills and knowledge, and could boost the local economy. They could also assist in improving the state’s autonomy from domestic business elites. At the same time, considering the political culture and weak institutional capacity in Somaliland, foreign actors may threaten the peace by affecting the delicate power balance between local actors and by introducing transnational interests.

Introduction

In the past four decades, Somaliland has experienced major political and economic changes, including impressive levels of economic growth and transition from clan-based representation to multiparty democracy. At the same time, the conceptual gap between the Western values and principles on which these reforms are based and the Somali system of governance is substantial. Despite not being internation- ally recognized as an independent state, Somaliland has an elected government and a modern judiciary system, even though these formal government structures are regarded weak. Instead, a plural system is in place where those who hold political and/or economic power include the Somali clan structure, national and local formal governance structures, religious authorities, Somaliland civil society, international humanitarian and development actors, and the corporate sector, including local and foreign actors. This has been described as a hybrid political order, where basic functions of security, representation and social services are provided by a combination of modern state institutions and a range of traditional and non- traditional non-state actors.

The political and economic growth has been realized largely through an informal and pluralistic approach. The system relies, firstly, on intricate informal collaboration between the government and the private sector and, secondly, on legal pluralism that dominantly draws on the xeer system in the absence of strong formal legal institutions. The xeer is the traditional customary law system that developed over the centuries and consists of cooperation contracts between clans. This system forms the most important source of laws and regulations, operating in parallel with modern institutions of politics and civil society.

Within this context, a range of small, medium and large business firms operate, and a number of those play an important role not just economically but also politically. In this brief, we ask what the role of local and foreign private sector actors is in maintaining peace in Somaliland. Our analysis draws on 25 in-depth interviews with stakeholders in the private sector, government, and civil society, as well as 5 focus group discussions. Data was collected in Hargeisa, Berbera, Lasanod and Erigavo from October 2015 to August 2016.

Basic Characteristics of Somaliland’s economy

Somaliland’s economy is private-sector led. According to a recent World Bank report (2016), the government’s contribution amounts to under 10 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). As Hagmann and Stepputat (2016) explain, livestock, telecommunications and remittances are among the key pillars of the Somali economy, and these are private-sector led and regulated only to a limited extent.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is very scarce, as Somaliland remains a high-risk context for such investments and is not internationally recognized. The few foreign Multi-National Corporations (MNCs) in Somaliland are present under special arrangements. These may involve the state, for example donor fund administrators like Mott McDonald, or private arrangements involving Somaliland entrepreneurs, such as Western Union, DHL and Coca-Cola.

Somali-owned MNCs, as well as domestic medium and large businesses have contributed to and shaped Somaliland’s post-1991 economy and state formation. These firms are mainly in the telecommunication, finance, energy and import-export sectors of the economy. Most are privately owned, while the few shareholder companies are labeled and identified with the clan of their top leadership.

The labeling of a business according to clan presents both opportunities and challenges for its operation. On the one hand, it gives the business protection. For example, if the business is targeted by government decisions that impact profits or restrict its operations, the company uses the clan structures to prevent such new measures from taking place. On the other hand, companies can be understood by locals to represent a specific clan, and this can cost them lucrative projects. There are cases where companies miss investment opportuni- ties simply because another clan resists such investment plans, since they perceive this as a rival clan expanding into their geographical or business-territory.

Because Somaliland is not internationally recognized, it does not have access to financial international institutions such as the World Bank and IMF, and thus cannot directly get loans from these financial institutions.

Considering both the de facto political status of Somaliland and its post-conflict reality, characterized by a weak economy and state, the local business elite has great influence on the process of state formation and stabilization. The main corporate players in the country lend the state money during periods of deficit, provide major contributions during emergencies such as droughts, and also contribute to a range of infrastructural and social projects. At the same time, because of the state’s dependence on such financial support, reciprocal relationships exist between the state and the dominant business class, where the former is unable to regulate the latter or introduce policies and practices that are unfavorable for these businesses. This may hinder Somaliland’s development and stability in the long run, for example leading to protectionist measures that close the Somaliland market to new economic players.

Maintaining the Peace: A Delicate Balance

After peace was restored in Somaliland, many powerholders – including business elites, politicians and religious leaders – accumulated wealth and enjoyed freedom and leverages that they did not have under the former regime and during the civil war. These powerholders play complementary roles to keep peace, but at the same time have no interest in state institutions that are powerful enough to regulate their gains. As such, this elite is involved in strenuous efforts to balance peace keeping with keeping the status quo in order to guard and advance their own interests. As a manager in a remittance company in Hargeisa put it:

After 1991, things have gotten better in Somaliland. We have increased living standards, business and political influence. It is in the interest of every- one, including the business people, to guard their gains as they do not want the country to relapse into conflict.

Business people play a key role in maintaining stability. At times, they are more legitimate and trusted than the state apparatus as they solve high profile disputes, including political stalemates and investment-related disagreements. They also contribute to infrastructure and are engaged in philanthropic activities, such as during droughts. The National Drought

Commission that was established in 2016 to address the consequences of a serious drought in the region largely comprises members from the business community. As a political analyst in Hargeisa states:

When there are stalemates – whether political, such as the stalemate be- tween the political parties or conflicts over presidential office term extensions, or business-related conflict […]

– an ad hoc committee is established, which mostly comprises of business people, civil society and elders.

At the same time as the business elite contributes to stability, larger companies have also been involved in investment and privatization-related conflicts. These conflicts are often triggered by clan and territory-related issues and further exacerbated by the absence of privatization laws.

Our informants emphasized that local companies affect state autonomy. For example, the private sector is largely unregulated because local businesses successfully lobbied against such regulations. This has led to loss of potential tax revenues and an unfavorable investment climate for foreign investors. In order for Somaliland to attract foreign investors – in particular MNCs– the necessary basic laws and regulations need to be in place and political decision making needs to be predictable. As argued by a senior consultant:

These investors need to know that their business is not at the mercy of the incumbent authority but that existing laws give protection to their business irrespective of whether the current government is in office or not.

An Unfavorable Investment Climate

Both domestic and foreign actors face challenges when investing in Somaliland, though the risks they face differ. As a consequence of such challenges, local investors have neglected the industrial sector. There are few business people who have for example invested in beverages, water bottling and detergents, leading to a situation where over 85% percent of all inputs used by firms are imported from outside Somaliland (World Bank 2016). Due to its geographical location and taxation practices, imports are relatively easy. Other factors that limit local investment include the unregulated market; unreliable security; the absence of technical skills locally; traditional businesses management practices; high costs of inputs such as electricity and land; and the lack of enforceable government policy. As highlighted by a development researcher:

The government does not guide private sector investment; this is the reason why the private sector lacks diversification. There are many water bottlers in Somaliland. All of them import the bottles, labels, and boxes from Dubai. The government could have created incentives for some investors to locally produce the packages, while others process the water.

Similarly, a combination of factors explains the limited number of foreign multi-national companies operating in Somaliland. The country’s investment climate is judged unfavorable because of low income levels and fragile security.

Other reasons for limited foreign investments include the absence of commercial banks and proper regulations, as well as the informal system of governance and decision making. Locally-owned private actors tend to contribute to creating market entry barriers in order to avoid competition and to enable themselves to continue their current capital accumulation.

Thus, the behavior of the large domestic companies risks impeding economic growth, as this incapacitates the state from regulating the business sector in ways that can attract foreign investors and increase competition.

Without foreign capital input, economic development opportunities will be limited. One important factor contributing to this situation is the lack of competition in the finance sector.

This leads to a situation where local businesses only have access to local Islamic banks, and those local banks do not provide sufficiently long-term business loans, while the conditions are not favorable to less connected potential borrowers. As a former employee of a large remittance company argues:

The longest period attained in investment that banks make is 36 months, if they make an extra effort their investment period will not exceed 48 months. No one knows whether political instability or conflict will take place, there are uncertainties, and this has led to short-term investments and a higher rate of profit that banks accumulate from their transactions.

Foreign Investment in Somaliland: Mixed Blessings

Foreign investment is necessary in Somaliland to improve the quality and choice of products and services, and boost the local economy by bringing in capital, job opportunities and other resources. The few foreign private actors that currently operate in Somaliland are seen to have that potential. For example, the foreign consultancy firms that administer donor funds have started to operate in Somaliland under the new ‘Somaliland Special Arrangement’, which gave birth to the Somaliland Development Fund (SDF). Foreign donors increasingly see these foreign corporate actors as alternatives to traditional ways of providing assistance.

The stated aims of such organizations are to transfer technical skills to Somaliland in order to build the capacity of the state and guarantee sustainability of development programs.

Similarly, foreign MNCs may provide resources such as jobs to the locals based on merit, something which young people we interviewed applaud:

We know that Somaliland is a young country which is not capable of creating jobs for the youth. Also, we are a clan-based society […]. If more investors arrive in Somaliland, they would recruit on skill and merit basis, and the current culture where educated youth need elders who can fix them a job, will stop.

Yet the Somaliland context is still a delicate one: local powerholders give precedence to pragmatic approaches and informal governance over the internationally-supported formal governance and decision-making structures. While such informal arrangements may benefit their business interests, local powerholders have also shown to subordinate their individual interests to state interests in situations where peace is really at stake. If pursuing their own interests can cause risks of violent conflict to the country, these local business elites have retreated in the past. Such actors are very aware of Somaliland’s history, and function within deep-rooted power and resource-sharing dynamics in which no actor holds the monopoly.

But do foreign investors fit into this context? Are they likely to disrupt these delicate power- and resource-sharing dynamics in a context where even innocent decisions can have serious repercussions for clan dynamics? What would be the effect of the transnational interests that such companies may introduce to this context? And how can foreign investors avoid that local powerholders are involve them in dubious deals which threaten to destabilize clan relations and raise questions of accountability and transparency?

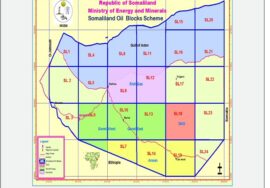

Our research participants caution against welcoming foreign corporate actors before political and economic realities in Somaliland change. They suggest that foreign investors do not understand local realities, and cite several cases where projects that involved foreign MNCs caused public and political outcry. They quote recent conflicts where the government tried to enforce agreements with foreign MNCs while local people resisted. Examples include seismic operations in the Eastern regions and the leasing of key economic infrastructures to MNCs.One development practitioner stated:

Many foreign investments such as the oil exploration in the East and transferring port facilities caused resistance. While the government wanted to enforce the agreements, at one point in 2014, the government established the controversial Oil Protection Unit (OPU), but withdrew after criticism.

Informants argue that the source of the resistance against development projects is not that people are against economic investments, but that the approach to these projects is not transparent. They argue that individuals have invested interests in these investments. In the absence of foreign investment laws, it is difficult to formally challenge the lack of transparency. An experienced lawyer and former government staff member argued:

Regulations and acts that would govern the investment should be developed before the investment is implemented. This would answer questions such as: Who should be involved in such agreements? How would parties benefit from the investments? How would local people benefit from the investments? Which act would govern the employees’ rights?

Conclusion and Recommendations

Since 1991, the dominant local business class in Somaliland has established and accumulated capital while having great influence on state building, economic development and peacebuilding. In recent years, however, there has been an increasing perception of exploitation by the business elite. The rapid increases of wealth amongst a small elite, combined with high unemployment rates amongst the youth, can easily lead to instability. One of the consequences of this reality has been an out-migration of young Somalilanders, at times through dangerous routes, towards Europe. As such, it is essential that Somaliland stimulates and guides its local economy, formulates the necessary regulations, and improves government capacity and integrity to lead economic transformation in the country.

The absence of regulatory frameworks for business and finance poses a challenge to local and foreign investments and can risk the fragile peace. Both the formulation and implementation of viable economic and investment policies and regulations in Somaliland require an increase in state capacity and autonomy from influential domestic actors. As such, this is likely to take time. It would require institutional coordination, harmonization and transparency of state decisions, and political leaders would need to build state capacity through recruitment based on merit. State autonomy requires increased tax revenues and reduced dependency on ad-hoc and informal forms of support from non-state powerholders, in particular the business elite.

While consensus-based and clan-based approaches have been central in regaining and maintaining stability and peace in Somaliland, existing approaches pose a challenge to transparency, accountability, economic development, state capacity and autonomy.

Foreign investments cannot be made without threatening the fragile peace if legal structures and institutions to regulate business and its financing are not in place. If Somaliland is to continue its economic growth, it will require successive governments to engage in deliberate and gradual economic and social transformation towards a long-term economic vision that promotes job creation, innovation and investment for all its citizens.

By Ahmed M. Musa, Uni Kenya