Somaliland Presidential Election 2017

Report on the Somaliland Presidential Election, 13th November 2017

This report presents the findings of the International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) to Somaliland’s third presidential election, held on November 13th 2017. The election saw three candidates competing to replace the incumbent, Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud ‘Silanyo’ of the Kulmiye (‘Peace, Unity and Development’) party: Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi ‘Irro’ for the Waddani (‘National’) party; Faisal Ali Warabe for the UCID (‘Jus- tice and Welfare’) party; and Muse Bihi Abdi for Kulmiye. Each ticket also included a vice-presidential candidate.

The Development Planning Unit (DPU) at University College London (UCL) and Somaliland Focus (UK) were invited by Somaliland’s National Electoral Commission (NEC) to act as coordinators of the mission, which was funded by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and project-managed by UCL Consultants Ltd (UCLC). The mission followed previous election observation missions by DPU and Somaliland Focus (UK) in 2005, 2010 and 2012, as well as observation of the voter registration process that preceded the 2017 poll.

Somaliland’s success in establishing a viable political system that combines customary structures with the representative electoral mechanisms of the nation-state has been impressive, especially given the lack of inter- national recognition of Somaliland as an independent nation. The 2017 election took place after considerable delay caused by technical and political challenges and drought and was preceded by the rolling out of a new voter registration system utilising biometric iris scan technology, designed to combat multiple voting issues that had compromised past elections.

The IEOM observed the elections in line with relevant regional and international benchmarks for observation of elections, including the African Charter on Democra- cy, Elections and Governance, and in line with the legal framework for the conduct of elections in Somaliland. The mission was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation and the Code of Conduct for International Election Observers, ratified by the United Nations in 2005.

The mandate of the IEOM was to observe, gather in- formation and report on the election, whilst maintaining strict independence, impartiality and professionalism. Observers were trained to avoid interfering in the electoral process, but to report accurately and methodically. Press releases and public statements were carefully worded to ensure impartiality and to reduce scope for misinterpretation.

The mission assembled a team of 60 observers from 27 countries, selected to balance gender, nationality and relevant experience. This included a five-member Coordination Team (Chief Observer, Election Analyst, Legal Analyst, Media Coordinator, Logistical Manager), which made logistical arrangements and observed pre- and post-election activities as well as election day itself and including campaigning activity.

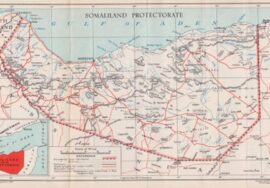

After intensive training in Hargeisa, the observation team deployed across Somaliland for election day, covering all six regions of Somaliland and 17 of the 21 districts, observing in 355 polling stations (22% of the 1,642 in operation), covering a mix of urban and rural locations as far west as the town of Seylac and surrounding rural areas and as far east as Erigavo, Las Anod, Xudun, and surrounds.

Opening procedures were observed in 27 polling stations, closing and counting in 30 stations and tabulation in 12 tallying centres. The mission was able to report a largely peaceful and well-organised polling day in areas observed, albeit with some concerns, including around inconsistencies in polling station management, some ir- regularities in the voting process, such as the issuing of unstamped ballot papers, and the prevalence of under- age voting.

The mission noted delays in tabulation and collation of results, which contributed to a tense situation in the days following the election, as rumours about results and allegations of electoral malpractice circulated, de- spite a ban on access to social media networks. The situation led to some violence, tragically including fatalities. At one stage, opposition party Waddani suspended its cooperation with the NEC and demanded that votes be recounted. Ultimately, Waddani’s leadership agreed to accept the results for the sake of Somaliland, while still maintaining they were incorrect, and on November 21st the NEC announced that Muse Bihi Abdi of Kulmiye had won the election.

The IEOM concluded that irregularities observed were not of sufficient scale or pattern to have impacted the final result and notes that no complaints were presented formally to Somaliland’s Supreme Court, despite the many grievances aired. Throughout the election period, Somalilanders demonstrated their support for the rule of law and constitutional process, voting peacefully and in significant numbers and the mission applauds this on- going commitment to peaceful participation in an impressively open electoral system.

However, the post-poll problems were deeply disappointing, and tension remains, with continued deep rifts emphasising the challenges still ahead in negotiating the transition from customary structures to representative nation-state politics.

As Somaliland continues its political journey, the IEOM makes a number of recommendations, including that the NEC and Somaliland government strengthen the legal bodies supervising campaigns and elections (especially formal dispute procedures); improvements to civic education and training for polling staff, political parties and voters; better transparency around the electoral process; that political parties use formal dispute resolution structures, improve female representation and refrain from inflammatory campaigning; that legislation be improved to ensure freedom of expression; and that campaign spending limits be introduced to improve the fairness of the contest. While underage voting remains a significant problem, the most obvious means of effectively addressing that lies in maintain- ing and updating the voter register so that its role as a comprehensive register of eligible voters improves with each future election.

On 13th November 2017, Somaliland held a presidential election, its third since declaring independence from Somalia in 1991. This latest election saw three candidates competing to replace the incumbent, Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud ‘Silanyo’ of the Kulmiye (‘Peace, Unity and Development’) party, who had chosen not to stand: Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi ‘Irro’ for the Waddani (‘National’) party; Faisal Ali Warabe for the UCID (‘Jus- tice and Welfare’) party; and Muse Bihi Abdi for Kulmiye. Each ticket also included a vice-presidential candidate: Abdirahman Abdullahi Ismail ‘Saylici’ stood for Kulmiye; Mohamed Ali Aw Abdi for Waddani; and Ahmed Abdi Muse Abyan for UCID.

The Development Planning Unit (DPU) at University College London (UCL) and Somaliland Focus (UK) were invited by Somaliland’s National Electoral Commission (NEC) to act as coordinators of the international election observation mission (IEOM). The mission was funded by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and was contracted and project-managed by UCL’s consultancy company, UCL Consultants Ltd (UCLC).

The involvement of both DPU and Somaliland Focus (UK) followed their participation in previous observation missions to parliamentary elections in 2005, the presidential election in 2010, district and council elections in 2012 and the voter registration process in 2016 and 2017. These missions were led by Progressio, a UK-based non-governmental organisation (NGO) working in Somaliland, which ceased operations in early 2017. Thus, DPU stepped into the leading role for the 2017 mission, joined by UCLC for the first time. Ultimately, the IEOM saw 60 members from 27 countries observe polling stations across all six of Somaliland’s regions.

Reports of the previous missions are available on the Somaliland Focus (UK) website (www.somalilandfocus.org.uk).

1.1 The Development Planning Unit (DPU) at UCL and Somaliland Focus (UK)

The Development Planning Unit (DPU) is an inter-disciplinary unit operating within University College London (UCL). It offers taught postgraduate courses and research programmes and undertakes consultancy work in inter- national development. The DPU’s mission is to build the capacity of professionals and institutions to design and implement innovative, sustainable and inclusive strategies at the local, national and global levels, that enable those people who are generally excluded from decision- making by poverty or by their social and cultural identity, to play a full and rewarding role in their own development.

Over the past years, DPU staff, particularly Dr Michael Walls, have maintained a strong involvement in development-related interventions in the Horn of Africa, and most specifically in the Somali areas.

Somaliland Focus (UK) was established in 2005 to raise awareness of the democratic achievements of Somali- land. Its members are individuals with personal and/or professional interests in Somaliland, including those from the Somaliland diaspora in the UK.

DPU and Somaliland Focus (UK) do not take a position on the international recognition of Somaliland, as we regard this issue as beyond our mandate. At the same time, we welcome the increased stability, security, and account- ability to citizens, which has in part been supported by the development of institutions of representative democracy in Somaliland. Democracy is about more than just elections – but elections are a vital part in establishing a legitimate system of representation.

1.2 International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) and elections

International election observation missions seek to pro- vide as comprehensive, independent and impartial an assessment of electoral processes as is possible given the context in which they operate.

Elections provide a means for the citizens of a country to participate in the selection of their government, on a ba- sis that is established by law. Governing institutions have democratic legitimacy when they have been granted authority by such a process to govern in the name of that population, who in turn hold them accountable for the exercise of their authority through genuine and periodic elections. That is the essence of legitimate, democratic, representative government. The right of eligible citizens to stand for election and to vote in accordance with their genuine preference in periodic elections, under reason-

able laws governing that eligibility to vote, is therefore an internationally recognised human right.

All observers on the mission signed a contract that explicitly committed them to adhering to this UN-mandated set of principles and code of conduct (see Appendix 2).

It is simultaneously the responsibility of voters, political candidates and party activists and officials to exercise the right to stand for election, to campaign and to vote within the reasonable restrictions of the law and in a peaceful Figure 1.1. IEOM training. © Michael Walls manner in which the best interests of the population as a whole are respected.

Election observation seeks to enhance transparency and accountability and, therefore, to promote public confidence in electoral processes. In so doing, it can also pro- mote electoral participation. This in turn should mitigate the potential for election-related conflicts. The converse is that election observation can reveal flaws in the electoral process and reveal scope for improvement. As such, an IEOM seeks to make a positive contribution to a given electoral process, without interfering in its conduct and without purporting to validate a specific result.

Missions operate under the remit of the Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation and the Code of Conduct for International Election Observers. These were ratified by the United Nations in October 2005, and are endorsed by 52 intergovernmental and international organisations, which are engaged in the pro- cess of supporting and constantly improving the practices associated with international election observation.

The Declaration of Principles represents an internation- ally respected commitment to assuring the integrity and transparency of international election observation missions. The 2017 International Election Observation Mission in Somaliland was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Principles.

1.2.1 Mandate

The IEOM was deployed to observe Somaliland’s presidential election on 13th November 2017 at the invitation of the National Electoral Commission of Somaliland (NEC). Under this mandate, DPU partnered with UCLC to organise deployment. The IEOM was and remains fully independent of the Somaliland authorities.

The Declaration of Principles defines international election observation as:

- the systematic, comprehensive and accurate gathering of information concerning the laws, pro- cesses and institutions related to the conduct of elections and other factors concerning the overall electoral environment;

Core funding for the IEOM was provided by the UK Government, through the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, although the mission was international in character, rather than a British mission as such.

- the impartial and professional analysis of such in- formation;

- the drawing of conclusions about the character of electoral processes based on the highest standards for accuracy of information and impartiality of analysis; and

The mandate of the IEOM was to observe, gather information and report, whilst maintaining strict independence, impartiality and professionalism. Observers were trained to avoid interfering in the electoral process, but to report accurately and methodically.

1.2.2 Structure

- the provision of recommendations for improving the integrity and effectiveness of electoral and related processes, while not interfering in, and thus hindering, such processes (see UN, 2005: 2).

The IEOM (which deployed a team of 60 observers from 27 countries) was led by Dr Michael Walls of DPU in the role of Chief Observer.

The limits of consensus. Report on the Somaliland Presidential Election, 13th November 2017 9

A five-member Coordination Team was in place ahead assembled in Hargeisa on 8th November. There, the IEOM of the arrival of the STO team, comprising: team underwent intensive training prior to deployment, including briefings on the pre-election context provided

- Chief Observer, Dr Michael Walls (New Zealand/UK); by Coordination Team members, and by other electoral stakeholders, including civil society members and party

- Election Analyst, Susan Mwape (Zambia); representatives.

- Legal Analyst, Ahmed Farag (Egypt);

- Media and Communications Coordinator, Conrad Heine (New Zealand/UK); and

- Logistical Manager, Andrea Klingel (Germany).

Support was provided by Carrie Goggin (USA) as Project Manager through UCLC, largely in London but also as part of the team in Hargeisa.

The responsibilities of the Coordination Team encompassed two main areas:

- making logistical arrangements for deployments of observers (usually described on IEOMs as ‘core team’ responsibilities); and

- holding meetings with election stakeholders and observing pre-election and post-election activities.

These latter activities are generally referred to on IEOMs as ‘long-term observation’, carried out by long-term ob- servers (LTOs); the compressed nature of this mission and team meant that the Coordination Team carried out both core team and LTO responsibilities. Stakeholders met and consulted with in gathering the material necessary for pre-election and post-election assessments included the NEC, relevant government agencies, civil society, media and political parties.

The Coordination Team assembled in Addis Ababa on 18th October and relocated to Hargeisa two days later. The bulk of the IEOM, namely the 55 members who made up the Short-Term Observer (STO) team, as-

The IEOM membership achieved near-gender parity, with 47% women and 53% men. Observers were drawn from 27 countries across six continents and offered a wide mix of election observation experience and knowledge of Somaliland and the region. Countries represent- ed included:

Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Egypt, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, Malaysia, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Senegal, South Africa, Spain, Sudan, Uganda, UK, USA, Swe- den, Switzerland and Zambia.

Initially the IEOM team included observers from the Somaliland diaspora, as had been the practice in previous election observations in Somaliland. However, on 16th October 2017, the NEC requested that no diaspora members be included, in order to avoid the potential for individual observers to be identified as allied with one or other of the parties contesting the poll. The late nature of this request, which the IEOM felt obliged to accept, as the invitation to observe was issued by the NEC, caused difficulties for the mission; financial loss as non-refund- able flights had been booked and insurance had been paid; loss of interpreters as diaspora members assisted in previous IEOMs with interpreting; from a recruitment point of view as these observers had to be replaced at short notice; negative media coverage; and disappointment for diaspora observers who had previously worked on EOMs and had been trusted supporters of democratic elections in Somaliland.

1.2.3 Methodology

Once deployed in-country from 20th October 2017, the Coordination Team undertook an analysis of the political context, the electoral environment, the media environment and the legal framework through desk research, consultations with key stakeholders and direct observation. In the process of pre-election observation, the team met with the NEC (on many occasions), the three main political parties, government ministries and agencies, the police and national security and intelligence, the judiciary, civil society organisations (CSOs), media organisations, academia and other stakeholders. The team also observed campaigning from all three parties.

Ahead of the IEOM, all mission members were required to complete an online international election observation training course (designed by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights) and to read an STO Handbook specifically assembled for the Somaliland IEOM. Observer training in Hargeisa was delivered over three days and covered aspects including the political his- tory of Somaliland, cultural background, the legal frame- work, pre-election findings and the role of the media, as well as practical aspects of deployment, logistics and security. A mock polling station role-play allowed observers to test their understanding of election day processes. External presenters, including representatives from the political parties, domestic observer organisation SONSAF (Somaliland Non-State Actors Forum), other civil society organisations and the Electoral Monitoring Committee of the NEC provided further insight.

Observers were dispatched in pairs across the six regions of Somaliland, thus working in 30 two-person teams, with each team accompanied by Special Protection Unit (SPU) personnel in all areas apart from Hargeisa city. In order to cover polling day and post-poll processes fully, observers stayed between one and four days in the field, depending on their area of observation and the time it took to observe district and regional level tabulation, before returning to Hargeisa. While in the field, observers met with local stakeholders, including the NEC Commissioner assigned to each region, the SONSAF Regional Coordinator, police commander and village elders as far as possible prior to election day.

The focus of the IEOM on election day itself was to observe all activities and processes, including the opening of polling stations, the voting process, the closing of polling stations and counting process. Following the conclusion of polling, IEOM activities continued with observation of district and regional aggregation procedures at district and regional tally centres across Somaliland.

Observations during election day were reported back with the help of four different evaluation forms: one for opening of the polling stations, one for each poll- ing station where voting was observed, one for closing of polling stations and the counting process, and the final one for the tabulation of results. In addition to the quantitative data, qualitative data was collected through comments entered onto the same forms, and through debrief sessions after election day, as well as through election day communications.

The IEOM issued a series of press statements during its observation of the elections (see Appendix 1). A press release on 27th October 2017 announced the arrival of the first observers in Somaliland. This was followed by a press release on 11th November 2017 to confirm the start of deployment of observers across Somaliland. The day after, an initial assessment of election day observations was issued congratulating the Somaliland people on a peaceful poll. In a further press release on 16th November 2017 the IEOM asked all parties to urge their supporters to accept the results once released and pursue complaints through legal channels. This request was reaffirmed in a further press statement on 17th November following post-poll unrest that led to the tragic loss of life. On 29th November 2017 the IEOM congratulated the new president in a press statement following the announcement of results by the Supreme Court.

A confidential preliminary report was submitted to the NEC on 20th November 2017 including preliminary findings of the IEOM, recommendations and conclusions relating to the election. It was issued while the process was still ongoing, and therefore reflected only the mission’s observations up to the conclusion of the counting process at polling station and district level on 17th November.

1.2.4 Observation coverage

The IEOM covered all six regions of Somaliland, and 17 of the 21 districts, despite limitations in terms of the size of the team and lack of infrastructure in remote areas combined with vagueness of maps, which prolonged some journeys between polling stations. The IEOM reached as far west as the town of Seylac and surrounding rural areas and, with the first participation in a Somaliland election of some in the easternmost regions, as far east as Erigavo, Las Anod, Xudun, and surrounds.

For the first time in the electoral history of Somaliland, maps were available indicating polling station locations. However, the maps were not very precise and, especially in urban areas, the concentration of polling stations was too high to identify individual locations. Nevertheless, their very existence marked an advance that can be built on in future elections.

The IEOM team observed 355 polling stations on election day, which represents 22% of the 1,642 in operation. Observers covered urban, rural and urban/rural boundary (peri-urban) locations in balanced proportion, with a split of 57% urban, 41% rural and 2% peri-urban locations. It must be noted that the greater distance between rural polling stations necessitates a trade-off between the objective of maximising the number of polling stations visited and that of visiting the widest geographical spread possible. Selection of polling stations for observation deliberately attempted to ensure the widest reasonable distribution in the knowledge that this would result in a lower total number observed.

thorough analysis of Somaliland’s media landscape and an integral part of the IEOM. The Somaliland media’s election coverage. coverage of the election, and the relative balance it gave to the respective political campaigns, was monitoring

There were three main aspects to the IEOM’s media optored on a daily basis for one month from the start of eration: the campaign on 21st October 2017 through to final results. As for past missions, a locally-based media

- Generating and coordinating media coverage of analyst (who also translated IEOM media material into the IEOM; Somali) was engaged for this task.

- Supervising the IEOM’s own relationship with the media (ensuring mission members adhered to media policy and did not compromise impartiality); and

- Monitoring coverage of the election campaign and the post-election period by media in Somaliland and elsewhere.

In addition, the Media Coordinator used the pre-poll period to gain a clear understanding of Somaliland’s media landscape and to network with media stakeholders.

Monitoring covered the scope of Somaliland’s media: newspapers, television, radio and online, including social media. The IEOM also notes the separate media monitoring project carried out by the Somaliland Journalists Association (SOLJA) and the NEC, which assessed media compliance with the media code of conduct that had been put in place by the NEC for the duration of the election campaign, but which was not connected with the IEOM monitoring function.

Mission media policy

In order to preserve the integrity and impartiality of the mission, the IEOM implemented a strict media policy. This sought to ensure that mission communication with the media was conducted via the Media Coordinator, who acted as media spokesperson and facilitated interviews with other team members (mostly, but not exclusively, Coordination Team members).

Team members were briefed on the importance of ensuring that mission media guidelines extended to per- sonal media, including social media, for the duration of the mission through to publication of the final report. In training, talking points (generally facts of the mission) and areas to avoid (especially political opinions about Somaliland and prejudging election conduct or result) were fully explained. Team members respected the policy, while continuing to speak to and write in the media, to the benefit of the IEOM.

IEOM media coverage

The mission’s message was communicated primarily via regular press statements over the mission’s duration on the ground and since, including for the launch of this final report. Four press conferences were held in Hargeisa, including an introductory press conference in conjunction with the National Electoral Commission (NEC) some days after the Coordination Team’s arrival. Social media (especially Facebook and Twitter via @ SomalilandFocus) was utilised to a greater extent than in past missions, with an STO team member also serving as social media editor, reflecting the particular local importance of social media. An extensive media mailing list was developed (building upon the list developed for previous missions), personal contacts made, and team members were encouraged to use their own contacts, for example in countries of origin.

International Election Observation Mission

Consequently, the IEOM was well covered in both local and international media, with Voice of America and BBC Somali (two international agencies very important locally) to the fore. Press statements were reproduced, mission members interviewed, and mission activities covered. International media also covered the mission directly, with the mission featured on (to name a few) BBC, Financial Times, Le Monde, RFI, Al-Jazeera, Radio New Zealand, Deutsche Welle, Bloomberg, the Finnish media, and more. Outside the mainstream media, the specialist publication Biometric Update also took an interest, thanks to the new voter registration system. Post-poll, team members have continued to ensure a regular stream of IEOM coverage.

With the press statements being (along with the press conferences) the first public indication of the IEOM’s viewpoint at the various stages of the mission, particular care was taken in formulating their wording, which tended to be collaborative efforts between the members of the Coordination Team. Press conferences were open affairs, with good and lively scope for questions and interviews from media present. Several press releases were made in the days following polling day, reflecting the need to strike a balance between timely release of initial findings from polling day (which, by election observation convention, needed to be before results were declared), conclusions based on later information, and in reaction to events.

Despite these efforts, the IEOM was at times subject to reporting that did not accurately reflect its findings; an ex- ample being a piece in the Financial Times, authored by the elected president, that described the election as having been “certified as free and fair by a 60-strong team of international observers” (Muse Bihi Abdi, 2017). The IEOM does not purport to ‘certify’ elections, and the term ‘free and fair’ is avoided in order to offer a more nuanced and constructive assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the campaign, voting procedures, tallying and reactions of media and other stakeholders.

The Financial Times article appears to have been the source for further inaccurate representation of the IEOM’s findings. The Media Coordinator addressed this and similar issues through social media posts, which pointed to the mission’s press releases, and has continued to monitor media and social media following polling day and the declaration of results.

- International election observation in Somaliland

The 2017 presidential election was the sixth poll held in Somaliland since 2002, following the two previous presidential elections in 2003 and 2010; one parliamentary election (lower house) in 2005; and two local council elections in 2002 and 2012. Each election was observed by members of the international community. Their assessments have been largely positive, albe- it with significant caveats (Adan Yusuf Abokor et al., 2006; Kibble and Walls, 2013; Lindeman and Hansen, 2003; Rip and de Wit, 2003; Simkin and Crook, 2002; Walls and Kibble, 2011).

The most recent of these observation missions were funded by the British government and required close partnerships with civil society organisations and net- works with Somaliland-specific expertise. For the 2005 parliamentary, 2010 presidential and 2012 local council elections, Progressio was invited by the NEC to facili- tate and organise the IEOM and to report their findings. In 2010 and 2012, Progressio was joined by DPU and Somaliland Focus (UK) in forming an observation team, and with Progressio ceasing to operate in 2017, responsibility for organisation of observers for the presidential election observation passed to DPU and Somaliland Focus (UK).

At the presidential election held on 26th June 2010, the IEOM saw 59 observers from four continents and 16 different countries cover 33% of polling stations across Somaliland’s six regions. The elections were found to be reasonably free and fair, although some problems were also noted in recommendations offered to the NEC and others in the final report.

On 28th November 2012, Somaliland held local district and council elections, with 2,368 candidates contest- ing 379 positions across the country. The IEOM covered the pre-electoral period, polling and counting on election day, as well as immediate and medium-term post-electoral processes. The outcome of the 2012 elections was determined to be peaceful; however, the team were unable to declare the election satisfactory as a result of significant and widespread irregularities (most significantly, including extensive multiple voting). Nonetheless, on balance, irregularities were assessed to have benefitted all parties, and the election was deemed to have represented a credible process in ex- pressing the will of Somalilanders in electing the offices of local government and for party selection.

Election campaigning was competitive and pluralistic, with seven different parties and associations fielding candidates. Furthermore, with the age of candidacy lowered to 26, an unprecedented number of youth participated, with a significant increase in female candidates standing: while in the previous local elections in 2002, only five women stood, 140 did so in 2012, although only 10 were actually elected (For more detail on Somaliland political history and elections to 2012, see Walls, 2014).

On election day in 2012, most polling station procedures and staff were positively evaluated by observers. The NEC was responsive and effective in addressing problems and concerns effectively. However, the absence of a voter registry and weaknesses in related safeguards – primarily the inadequacy of the indelible ink used on voters’ fingers to indicate their vote had been cast – made polling vulnerable to multiple voting. In advance of the next elections, the IEOM recommended that Somaliland adopt a robust system for voter/citizen registration, in order to deter fraud and improve confidence in the electoral process. We are delighted to note that such a register was completed prior to the 2017 election; a point which we address in more detail below and in a separate assessment (Schueller and Walls, 2017).

Political background and elections

In May 1991, Somalilanders unilaterally declared the resto- ration of the sovereignty they briefly enjoyed between 26th June and 1st July 1960, and have sought international recognition of that sovereignty since. From 2001, a series of elections and electoral processes, including a constitutional referendum in 2001, have taken place in generally peaceful fashion. Notably, that succession of elections saw the orderly transfer of power following the 2010 presidential election, when the incumbent accepted defeat, and at- tended the ceremony in which he relinquished power to the victor. A rare event on any continent.

Somaliland’s hybrid system of governance combines clan leadership with a representative democratic system. Parliament is bicameral, consisting of a lower House of Representatives and an upper house called the Guurti (council of elders). The House of Representatives and the Guurti each have 82 seats, with MPs in the lower house elected by popular vote, and Guurti members appointed by kinship groups. The Guurti has often been instrumental in consensus building and settling disputes.

In line with the Constitution of Somaliland, passed in 2001, only three political parties can be registered at any one time, and to contest parliamentary and presidential elections. Local council elections are used to determine the identity of those three parties, with those elections open to political associations and previously qualified parties, provided that each contesting organisation meets the rules established in relevant legislation, including payment of a substantial deposit. The three political entities that receive the greatest number of votes across all regions are deemed to be eligible to register as full parties and to compete in presidential and parliamentary elections. That system is intended to promote inter-clan dialogue and alliance.

In the 2010 presidential election, Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud ‘Silanyo’, the candidate for Kulmiye, defeated the incumbent president, Dahir Riyale Kahin of UDUB and Faisal Ali Warabe of UCID (in the 2003 presidential election, Silanyo had been narrowly defeated by Riyale). The subsequent local council elections, which took place in 2012, ushered in Waddani, a new player (at the expense of UDUB) while retaining Kulmiye and UCID for the 2017 presidential election.

This latest presidential election was originally scheduled for June 2015. However, in March of that year the NEC called for a nine-month delay in those polls, in order to allow time for significant political and technical chal- lenges to be addressed, including compilation of a voter register. Against this backdrop, the Guurti intervened by extending the tenure of the incumbent president by two years – to March 2017 – amidst protests from many

who viewed the nine months requested by the NEC as sufficient. The incumbent president was himself widely understood to be keen to see elections take place as early as possible.

In January 2017, the three political parties agreed to postpone the elections by a further three months. Al- though the NEC was technically prepared to hold the elections, the serious drought situation in Somaliland had displaced many citizens and would have had ad- verse effects on the issuance of voter cards and on voting itself, exacerbated by the policy requiring voters to vote at the locations at which they are registered. In March 2017, the NEC announced 13th November 2017 as the new date for the presidential election.

The November 2017 election constituted an important step in the consolidation of Somaliland’s representative democratic institutions. The fact that the incumbent president was not contesting meant that there was certain to be a change in leader, which heightened political tensions, and two of the three candidates were con- testing for the first time. The stiff competition between Kulmiye and Waddani was epitomised in the intensity of clan-based politicking, character assassination and isolated incidences of violence in the midst of the campaign. Yet the elections accorded Somaliland an opportunity to strengthen democracy and to demonstrate a culture of peaceful political transition.

2.1.1 Presidential candidates and political parties

Three political parties contested as follows:

Of the three candidates, only Faisal Ali ‘Warabe’ had con- tested a presidential election before, although all three were well-known public figures. Abdirahman Mohamed ‘Irro’ had been Speaker of the House of Representatives for some years, and formed Waddani as a result of a split with Faisal Ali’s UCID party. Muse Bihi Abdi is well known as a military commander from the days of the insurgent struggle against Siyaad Barre, and in relation to civil con- flicts that erupted in Somaliland in the early 1990s, after the collapse of the Siyaad government.

Legislative framework for elections

The IEOM’s aim was to provide an objective, impartial and balanced assessment of the electoral process in Somaliland. To achieve this, the mission assessed the constitutional and legal framework governing the election and its consistency with the international bench- marks for democratic and credible elections, which Somaliland has domesticated.

- The regional and international instruments referenced include:

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) 1948;

- The African Charter on Human and People’s Rights; and

- The African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance.

Central to the legal framework that governs democratic elections in Somaliland is the 2001 Constitution. That framework further includes subsidiary legislation as follows:

- The Presidential and Local District Council Elections Law 2001 (as amended);

- The Voter Registration Law 2007, as amended in 2014 and renamed the Civil and Voter Registration Law (Law No: 37/2007);

- Somaliland Voter Registration & Election Regulations, Voter Registration & Election Code of Con- ducts; and

- The Political Parties/Associations Law (Law No. 14/2001) and its Amendments in 2011.

It was noted that the legal framework is generally compatible and in compliance with sub-regional, regional and international standards. However, the areas of party and campaign finance, and the rights of persons to vote were noted as needing attention.

The IEOM recommends consolidation of all the election-related laws (Presidential, Local, House of Elders (once issued), House of Representatives elections) in one comprehensive legislative package to facilitate accessibility to stakeholders and researchers.

Citizenship

Article 4 of the Constitution of the Republic of Somali- land states:

Any person who is a patrial of Somaliland who is a descendent of a person residing in Somaliland on 26 June 1960 or earlier shall be recognized as a citizen of Somaliland…

Although the Constitution and Law No. 22/2002 lay down the grounds for Somaliland citizenship, there is no mention of specific ethnicity required for eligibility for citizenship. The legal framework only sets the date of independence as the main criteria to determine who is a citizen and who is not.

There are notable differences between men and women when it comes to citizenship rights. These differences are apparent in the law giving citizenship to any descendants of a male Somalilander resident in the territory of Somaliland on or before 26th June 1960, but not to the descendants of a comparable female Somali- lander. Other differences in treatment of males and females under law exist in how the law treats marriage to a foreigner and the conditions for acquiring and losing citizenship.

Inclusivity and equal suffrage are two important pillars of the democratic process. Although Somaliland is not a signatory (yet) to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) or the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which forbid any discrimination on the basis of gender, the IEOM suggests the citizenship law be amended in order to be consistent with the obligations Somaliland has committed itself to in Article 10 (2), and Article 8 (1) of the Constitution.

- Electoral institutions and stakeholders

3.1 National Electoral Commission (NEC)

Article 17(1) of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG) recognises the critical role of a competent, efficient and capable election management body, for the successful conduct or management of elections, which in Somaliland are conducted under the Plurality Majority System (First Past the Post), where a candidate with the highest number of votes is declared the winner.

The National Electoral Commission of Somaliland (NEC) is the body charged with the responsibility of managing and supervising elections in Somaliland. It is established under Article 11 of the Presidential and Local Council Elections Law No. 20.

The NEC is responsible for managing all the crucial aspects of the elections including: registration of voters, delimitation of electoral boundaries, conducting voter education, setting a specific election date in line with the Upper House (Guurti) decision on the term of the incum- bent. The NEC draws its own budget and is accorded financial and administrative autonomy in the discharge of its mandate.

The NEC is supervised by its commissioners who are nominated, and subsequently appointed, through consensus from the political parties, legislature and executive. Nominations of the seven commissioners are made in the following proportions: the Somaliland President nominates two; the Guurti nominates two and each of the three registered political parties nominates one. Nominated commissioners are then ratified by parliament using an absolute majority system, which ensures transparency in the nomination process. The commissioners are given a five-year term.

The current commission was inaugurated in 2014 just be- fore the commencement of the voter registration exercise, which was to be followed by the originally scheduled presidential election in June 2015.

Stakeholders expressed concerns over the tenure of office for the commissioners. It was pointed out that the legal provision of a five-year term is insufficient as it results in a loss of institutional memory, exacerbated by the practice of replacing most or all commissioners at once. The commission responsible for the 2017 election had only one member who had served in the previous commission.

The NEC has a decentralised structure which runs at polling station, district, regional and national levels. The NEC employs temporary staff to work in the polling station. Recruitment of polling staff is largely drawn from universities and institutions of higher learning competitively.

By and large, most stakeholders expressed confidence in the NEC. They described the NEC prior to the election as professional, impartial and capable of conducting credible elections. However, that consensus was lost in the post-election period, when the Waddani party in particular attacked the NEC, alleging procedural inconsistencies and ballot stuffing.

3.2 Legal bodies

In order to allow a communication channel between the NEC and the political parties, the Political Parties’ Code of Conduct established an Election Task Force (ETF), comprised of representatives from the three political parties. The ETF also has an advisory role to NEC and an alternative dispute resolution function, whereby the ETF was intended to work closely to mitigate any potential conflict between political parties to resolve such conflicts through dialogue before escalation.

Given the importance of the ETF role, the IEOM noted the potential benefit of making the body a permanent entity and also in enhancing its legal status, providing it with more powers, including the right to issue decisions that are binding on political parties and backed with enforcement ability.

At the start of the IEOM, an Electoral Monitoring Committee (EMC) was already in existence, having been formed for the voter registration process. Although some personnel changed prior to the election, the EMC’s functional and operational procedures remained similar throughout its existence. Chaired by Suad Abdi Ibrahim, previous Country Director for the NGO Progres- sio, the EMC was empowered to receive and assess for- mal complaints and to issue binding decisions, including the imposition of penalties. The EMC was based inside the NEC compound, and operated as a part of the NEC.

In our view, it would be advantageous if criteria were established for the selection of members of the EMC, ensuring the presence of different stakeholder representatives,

including representation from the judiciary, Public Prosecutor’s office, media, CSOs, lawyers, religious leaders and customary elders. The IEOM also recommends that the EMC’s role be enshrined in law, confirming its independence and its right to make and enforce binding decisions. Additionally, we see advantage in establishing the EMC as a permanent committee of the NEC.

Another potentially important alternative dispute resolution mechanism is traditionally offered in Somali society by ad hoc mediation committees, of which the most prominent for this election was an Eminent Group consisting of three ex-vice presidents, Abdirahman Aw Ali, Ahmed Yusuf Yasin and Hassan Isse Jama. The group was formed to offer a means of mitigating potential conflict between political parties and to assist in solving such conflicts through dialogue. In contrast to the ETF, the IEOM considers that the strength of this and similar groups resides in their informality, with the legitimacy of the group derived from the acceptance of the conflicted parties with regard to any role they might play. This approach has a strong foundation in Somali custom, and the group themselves were keen to rein- force their ad hoc nature to the IEOM.

In general, Somaliland’s customary systems play a key role in supporting institutional arrangements. For example, communication between the NEC and the courts, and between the NEC and political parties each involve the extensive use of informal channels, as much or more than formal ones. The advantage of this is it can be faster and more efficient than relying on the channels of bureaucracy, but conversely, the lack of a structure to such procedures prevents formal recording and therefore limits public access. It also reduces the scope for the introduction of structural improvements to increase the efficiency of these organisations.

Such lack of clear structure and definite mandate made it very difficult, in some cases, to spot weaknesses and suggest feedback when needed. For example, the pro- cess concerning the decision to block social media from the late afternoon of polling day and for several days after, remained unclear for CSOs and other stake- holders. There was a lack of clarity around which entity issued this decision, whether it is issued from the competent authority or not, and on what legal points such decision was based, in order to be able to challenge it in court. (The social media ban is addressed more fully in Section 4.3.2.)

The relationship between the political parties and the NEC also often appeared to lack clear lines of communication designed to involve the political parties in NEC decisions. Although the ETF had an office in the NEC compound, and they worked closely as a channel of communication between the NEC and parties, there was no mechanism to ensure the involvement of the ETF in the decision-making mechanisms of the NEC, and the parties themselves acknowledged that the flow of information back to the party from the ETF was patchy at best.

For example, while party representatives on the ETF were provided with a full copy of the voter register prior to the election, the IEOM’s own enquiries revealed that it took more than a week for the register to reach the party itself in one case. There appeared to be considerable informality in internal party structures in general, which also affected communication flows in other in- stances.

For example, although the IEOM was informed of the impending introduction of a new procedural manual designed to provide a framework for dealing with challenges to the election results through the Supreme Court, these procedures were not available sufficiently in advance of the election for political parties to under- stand each step in the process and to make appropriate preparations. Indeed, while we were able to obtain a copy of the procedures, it was difficult to ascertain whether the copy we possessed remained a draft or had been formally adopted.

3.2.1 Electoral dispute resolution

The IEOM noticed that political parties largely refrained from filing official complaints with the EMC or through the courts. Although the dispute resolution system was in place, we noted specifically that:

- The NEC and EMC had a clear sequence describing the manner in which complaints were to be processed, but lacked detail of how each com- plaint would be heard, or the time frame within which the disputed parties could submit evidence or present a defence.

- While the EMC plays a vital role and has significant powers, this important role is undermined by the lack of an explicit mechanism by which the EMC decisions should be enforced.

- Although the IEOM was informed that there is a procedural framework outlining the process to be used in the case of any challenge to the presidential results through the Supreme Court, that procedural pathway was not available early enough to give political parties a chance to pre- pare for any potential court action.

The IEOM noted positively the role of the alternative dispute resolution (ADR) initiatives, such as the Eminent Group of ex-vice presidents. The ETF, which included representatives from each political party, also

appeared to be a potentially useful vehicle for avoiding or containing conflict. It is important to note that politiing

Political parties generally tend to seek resolution of problems through dialogue, as is customary in Somali contexts. These customary channels were vital in addressing the discord that erupted on the evening of 16th November, when violent protests claimed several lives.

The Electoral Monitoring Committee

As noted above, the NEC established an Electoral Monitoring Committee, which was responsible for monitoring political parties in line with the political party code of conduct. The EMC played a crucial role in ensuring adherence to the code of conduct as well as the party dispute resolution prior to the election.

While the EMC is crucial to improved inter and intra party cohesion, there was a mismatch between the role of the EMC and the political parties’ understanding and expectations of it. On the one hand, concerning the EMC guidelines on investigating any violations of the political party code of conduct, the EMC remained dependent on formal filing of complaints and provision of evidence by the complainants. On the other hand, the view was expressed that the EMC should have been more proactive in identifying and investigating violations. Some interlocutors stated that it was the perceived complacency of the EMC and the expectations that it be proactive that were behind the failure to submit formal complaints.

3.3 Civil society

Somaliland has an active civil society, and the Constitution of Somaliland guarantees freedom of association. The IEOM noted the good working relationship between civil society and the NEC especially in conducting civic and voter education. CSOs were also instrumental in facilitating the training of political party agents and observing the whole process. Organisations such SON- SAF, the Human Rights Centre Somaliland, SOLJA and Academy for Peace and Development (APD) played an active role in conducting voter education, training and deploying citizen observers.

3.3.1 Women’s participation

Women are largely marginalised in political and elective positions in Somaliland, and the country falls far short of the minimum ideal 30% threshold for female representation in political decision-making suggested by UNDP to achieve the critical mass necessary to effect meaningful improvements in women’s political participation more generally (UNDP, 1995: 108-109).

While the Constitution of Somaliland has provision for the rights of women, there are a number of systemic factors that do not provide an enabling environment for women’s participation. This is indicated by the low number of women in elective positions and key decision-making bodies such as parliament and cabinet. Among the key factors that limit women’s participation is the absence of a legislative framework that provides affirmative action for women. The other is the inability of political parties to pro- vide space for women within their structures.

Although women played a central role during the campaign period and as voters (and as polling station staff), systemic barriers and cultural limitations do not provide the requisite space for women to participate freely in the political spaces. The IEOM noted reports of some women being intimidated for supporting certain political parties. As an evolving electoral democracy, Somaliland should provide an enabling environment for more women’s political participation and, specifically, representation.

3.3.2 Youth participation

Youth participation in the electoral process was very evident during the campaign period, with young people visibly the most vibrant campaigners. They were also instrumental in working as polling station staff and as domestic observers on election day. However, the absence of youth in some key aspects of the process such as civic and voter education was also notable. There therefore re- mains a need for favourable policies that enhance meaningful youth participation.

3.3.3 Participation of marginalised groups

There is no legal provision that focuses on the ability of people living with disabilities to participate in electoral processes, or those who are socially marginalised. While there is need for policies that provide an enabling environment for such groups, it is worth noting that the NEC did recruit some people with physical disabilities as polling station staff on election day.

The Somaliland population also includes a number of occupational caste groups, sometimes referred to collectively as Gabooye, but more specifically representing groups who identify themselves as Tumaal, Yibr, Ma- dhiban and Musse Dhiriye (Hill, 2010). Prevented by custom from intermarriage with the more numerous Somali clans, these caste groups have historically been associated with occupations including metalwork, leather work, hairdressing and other trades, and have experienced significant marginalisation in Somaliland society. This is strongly reflected in the political sphere, where the dominant clan groups have held a near-monopoly on political decision-making.

Amongst other features, the 2017 presidential election was notable for the inclusion – largely on the Waddani platform – of vocal supporters from these marginalised groups. However, they remain significantly under-represented in all political fora, and there remains no methodical effort to improve that situation. The possibility has long been discussed that quotas might be introduced for women and for those from the Tumaal, Yibr, Madhiban and Musse Dhiriye groups, but as yet no such measures have been introduced.

- Media and the election

4.1 Media landscape in Somaliland

Somaliland has a challenging media environment: eleven newspapers, fourteen television stations, around 60 important websites and one (state-run) radio station. Both Somali and English-language media are active, with BBC Somali and Voice of America both particularly influential. While state media exists, private owners are the norm, and in general, the media is not noted for its impartiality.

Media regulation is weak, and the training environment for media poor. Social media wields enormous influence, particularly among Somaliland’s youth, to good and malign effect: while it has grown hugely and hosts some of Somaliland’s most influential voices, it has also given voice to ‘fake news’, which was a significant issue over the election campaign, and remains one (with the IEOM itself the target at times).

Thus, media monitoring is a particularly important aspect of the observation, in order to promote future best practice, for elections and in general. In this context, the IEOM saw a greater effort to engage with the local media landscape than on past missions, building on separate work by Somaliland Focus (UK) to foster greater media freedom in Somaliland.

From arrival in Somaliland, the Coordination Team, and especially the Media Coordinator, sought to build on past missions and work by Somaliland Focus (UK) and others to engage with and understand the media landscape: the challenges, the legal background, issues around media persecution and freedom of expression, the implications of the media code of conduct for the election period (with the imposition of the code itself, and monitoring of the media’s, and the authorities’ adherence to the code by SOLJA in conjunction with NEC both developments welcomed by the mission), challenges around social media and ‘fake news’, and issues of media quality and lack of training and resources.

Coordination Team members met with human-rights campaigners, media members, media organisations including the Women in Journalism Association (WIJA) and SOLJA, civil society and media advisers to extend the mission’s media knowledge and contacts.

The Media Coordinator attended a pre-poll event focusing on ‘fake news’ in the election campaign, and coordinated a roundtable meeting assembled by invitation of media stakeholders at the SOLJA offices, which was well attended and deemed to be valuable by attendees. Following this, the Media Coordinator spoke on the international view of Somaliland’s media landscape at the SOLJA annual conference.

The roundtable discussion covered a diverse range of subjects, including media freedom, the legal environment, the international viewpoint, training and resources, and social media and fake news. Of particular note was its focus on the role of women in the media: the mission has concerns about, in particular, lack of access of female journalists to resources offered to male journalists, for ex- ample by SOLJA.

The IEOM was particularly concerned about the decision to suspend access to social media from the evening of polling day for a period of approximately one week. While concerns about inflammatory online material and the dis- semination of false information and rumours in a tense environment were understandable, the implications for freedom of expression and local information generation were troubling.

However, the mission also notes positive developments, including the ground-breaking televised debate between the presidential candidates and the prospective launch of an academic course on journalism at the University of Hargeisa.

The IEOM considers the media code of conduct to have been a particularly important feature of the 2017 election in guiding media coverage of the campaign. However, it offers guidelines rather than guarantees on how the media should carry out its tasks and over the election media did not always follow the code to the letter.

Yet it represents a positive and necessary instrument in holding the media to account, something very much needed in Somaliland’s media environment. It is no- table that much discussion around the media and the election focused on the idea of a more permanent media code of conduct beyond the election. The IEOM supports this, and recommends enshrining the media code of conduct in law to ensure compliance from both media and government, extending its applicability be- yond the election period and having it cover all media, including social media.

In general, attempts to regulate the media must be ac- companied by more resources for media (especially training) and legal reforms to provide protection to journalists doing their job and to protect media freedom in general. These would all be positive developments for the media in Somaliland.

4.2 Media coverage of the election

In general, the IEOM noted improvements from past elections in editorial balance (both in volume of coverage and partiality of coverage). However, issues remaining around balance of advertising in the media, with the lack of campaign spending limits reflected by higher levels of advertising in the media for richer political parties.

Over a period of one month from the start of campaigning, around 13 local newspapers, 14 TV stations and 60 websites were monitored daily to examine how fairly they reported the election campaign as well as the election itself on polling day. How the media adhered to the media code of conduct throughout the election campaign period to polling day was also monitored.

In general, the media adhered to the code of conduct and fairly reported all political sides. Although the local newspapers had their own affiliations, (for example Dawan which is state-owned, Somaliland Today, which is owned by a Waddani official, etc) when it came to re- porting, they were generally fair and gave a good picture of each day’s campaign party and the highlights of the candidate’s speeches. The media monitoring committee set up by NEC and CSOs including SOLJA was effective in noting breaches of the media code of conduct.

Radio Hargeisa, the only state-owned radio station in Somaliland, gave a fair share of its coverage to each of the parties. As Radio Hargeisa is on air 12 hours each day, this was the arrangement during the campaign period:

- 25 minutes of news coverage of each party on its campaigning day

- 25 minutes of special programmes on each par- ty during its campaigning day

- 20 minutes of reading each party’s manifesto during its campaigning day

Those coverage conditions were well managed and monitored by the media monitoring committee (all parties had the right to submit a complaint to the committee).

State-owned Somaliland National Television, which is on air almost 24/7, also gave fair coverage in its pro- grammes to the three parties under the supervision of the above-mentioned committee. It gave coverage of:

- News about each party’s campaigning in all regions of Somaliland on its campaigning day, focusing on the region where the candidate was during that day;

- Full speeches of each candidate during their party’s campaigning day (speeches were some- times censored if deemed to contain insults to other candidates or individuals).

In the run-up to polling day, newspapers published infographic information on the voting process, including how to vote at polling stations. Infographics (produced by Hoggaamiye.org, an initiative of the Inspire Group, organisers of the pioneering televised presidential de- bate screened just prior to the start of campaigning) were also circulated via social media (although with relatively low viewing figures, despite the high level of social media usage among Somaliland youth especially).

Following polling day, there was a high level of live media coverage of the announcement of results and im- mediate reports of the reaction of the various political parties. The reaction and eventual acceptance of results by the opposition parties was also well covered, with a range of different views from editors and commentators.

However, the tense post-poll environment was also ap- parent in the media. Following publication by two sites, Hadhwanaag News and Balligubadle News, of abuse of the elected president and claims that results were rigged and illegitimate, the government ordered the telecommunication companies to block the two websites.

Following the new president’s inauguration the courts ordered the ban lifted. Notable efforts were also made by the media to reduce tensions following the highly contested campaign, including publication of photos of the new president and the main opposition leader meeting and openly hugging at the funeral of a public figure.

4.3 Media freedom

4.3.1 Harassment of journalists and media outlets

Although freedom of expression is guaranteed under Article 32 of the Constitution of Somaliland, legal protection for media is weak (despite much debate about legal reform, the media is dealt with by criminal, not civil law), as is media regulation and training. Harassment and persecution of journalists and media bodies is a constant issue (albeit to a less serious degree than in Somalia, where numerous journalists have been killed), prompting concern from international media protection organisations including Reporters Without Borders, the Committee to Protect Journalists and Somaliland Focus (UK).

It is notable that even during the campaign, persecution of journalists was ongoing: the closure of Kalsan Television as a result of an apparently arbitrary decree by a government minister, despite the existence of the media code of conduct, was particularly concerning. Kalsan’s permit was revoked and suspended after it was accused of twisting an incident in Las Anod where the Kulmiye presidential candidate was giving a speech and shots were fired during the event.

It is the IEOM’s conclusion that Kalsan’s reporting of the incident left something to be desired, but the way it was handled by the Somaliland government was not in line with the agreed code of conduct. Without any consultation or involvement from the NEC, the Ministry of Information took drastic action against the station, moving to suspend its broadcasts (although the station continued to operate).

It is further regrettable that, under the new executive, persecution and harassment of media remains a feature of the Somaliland media landscape: at the time of writing, several post-poll incidents have been noted by the Committee to Protect Journalists, the Human Rights Centre Somaliland, and others (see CPJ, 2018).

4.3.2 Social media ban

The IEOM observed with concern the blockage of social media, from the late afternoon of polling day and for several days after, which had troubling implications for freedom of information and expression, which are important pillars of democratic elections. The decision effectively violated Articles 30 and 32 of the Constitution of Somali- land, as well as several international standards, including: The United Nations Human Rights Council Resolution A/HRC/RES/32/13, the African Commission on Human Rights and Peoples’ Rights ACHPR/Res. 362(LIX), Art. 19 (2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and others.

While the rationale for blocking social media was clear enough – namely, a desire to minimise the spread of rumours, conjecture and false news about results in the days in which counting and tallying was to take place

– its effectiveness remains questionable. While it can- not be disputed that, rumours were rife through that period, the IEOM is of the view that the measure may not have achieved sufficient positive effect to justify the restriction of access to information. Indeed, with wide- spread circumvention of the ban through usage of VPN networks, our impression is that the ban was largely futile. Furthermore, as rumours continued to circulate, it could also be said that the ban potentially compromised one important means of debunking them.

The Human Rights Centre Somaliland attempted to ac- quire an injunction from the courts preventing the shut- down using similar reasoning, but was unsuccessful.

- Pre-election observations/assessment

5.1 Voter registration

Somaliland’s NEC is responsible for conducting voter registration and maintaining the voter register. The right to vote and be registered as a voter is guaranteed under Article 22 of the Constitution of Somaliland. Citizenship is a requirement for voter registration. The procedure for registration of voters in Somaliland is contained in the Presidential and Local Council Elections Law, 2001.

The only previous concerted attempt to register Somali- land voters prior to an election took place in 2008/9 and resulted in a major political crisis (Walls, 2009a). The registration process was marred by multiple registrations, with officials routinely ignoring procedures for the col- lection of photographs required for the facial recognition system, and for the collection of fingerprints from regis- trants (Grace, 2009; Mathieson and Wager, 2010). While that crisis was eventually resolved sufficiently to permit the 2010 presidential election to take place relatively smoothly (Walls and Kibble, 2011; Walls, 2009b), the register itself had been so discredited as to make it politically toxic and, in 2011, the House of Representatives elected to nullify it. These difficulties underlined the challenges the NEC faced in organising and implementing a new voter registration process.

While it is not possible to ascertain the number of otherwise eligible voters who were unable to register, and therefore to vote, that number coupled with the number who did not collect voter cards does represent a significant flaw in the registration process, and represents a violation of the right to vote as guaranteed in Article 22 of the Constitution of Somaliland.

5.2 Civic and voter education

The NEC was responsible for developing materials, circulating messages and mapping areas as well as monitoring the process, which the NEC discharged to civil society and other electoral stakeholders. It was noted that the voter education might have been inadequate as a substantial proportion of voters on polling day required assistance to vote. While some must certainly have been illiterate, the extent of assistance requested in many poll- ing stations suggested that some proportion of those must have been unfamiliar with procedures.

The African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance places a responsibility on the state to ensure to encourage full participation in electoral and development processes.

Article 15 of the Presidential and Local Councils Elections Law stipulates that the NEC is responsible for managing activities aimed at raising voters’ awareness of electoral procedures. While the NEC worked with various stake- holders such as civil society and the media in conducting civic and voter education, there were varying views among stakeholders on the adequacy of the voter education.

The IEOM heard that the finances allotted to voter education were not sufficient to enable civic educators cover all areas. The NEC does not conduct the continuous civic and voter education which is central to improving people’s understanding of voter processes.

5.3 Political parties and candidate nomination

The number of political parties in Somaliland is stipulated by Article 9 of the Constitution of Somaliland as no more than three. This measure is intended as an important mechanism for deterring clan-based politics by forcing clan groups into alliances that cover significant portions of Somaliland. The operationalisation of this limit on political parties is undertaken through the political parties’ law.

The three parties that actually compete are dictated, in principle every ten years, by the results of what should be every second local council election (the most recent

of these being held in 2012). All established political parties and political associations that meet the legal requirements for registration are entitled to compete in local elections, with the three who attract the most votes from all the six regions gaining eligibility to register formally as parties and to compete in subsequent presidential and parliamentary elections. By design, there is no provision for independent candidates in any electoral contest – successful candidates from losing parties in local elections must transfer their member- ship to a registered party. Since 2003, Somaliland has experienced reasonably peaceful alternation of power between parties. Generally, political parties in Somali- land have fairly well-developed institutional frameworks and national representation.

Nominations within the political parties are mostly clan- driven, and parties nominate their own candidates. In the event of any intra party disputes and conflicts, the NEC is mandated to help resolve such issues. As a means of enhancing party cohesion and consensus, the NEC has periodic meetings with the representatives (candidates) to update them on key developments. Further, the EMC monitors and ensures adherence to the political parties’ code of conduct (which is not a legal document but is intended to govern the political party space and promote best practices). The IEOM noted the continued violation of this code by the parties, with both Kulmiye and Waddani penalised by the EMC for violating the code at different times.

5.4 Political campaigning

The campaign period for the 2017 presidential election commenced on 21st October 2017. Although the law provides for a campaign period of up to one month prior to election day, the campaign period was scheduled for 21 days. Each political party was given seven non-consecutive campaign days, with the whole day being dedicated to a particular party. The campaigns were largely peaceful with isolated incidents of violence, mostly in Hargeisa and Burco.

Some stakeholders, including the EMC, confirmed re- ports of violence, with some political parties being penalised by the EMC for violating the code of conduct. However, the IEOM noted the absence of strong mechanisms for compelling parties to respect penalties im- posed by the EMC for violations of the code of conduct.

The IEOM noted the use of inflammatory and derogatory language by some of the candidates during the campaign period. In the second week of campaigning, Kulmiye and Waddani engaged in a divisive war of words and the two candidates used their respective campaign platforms to slander one another.

The campaigns mostly took the form of rallies and street mobilisation. Although held just before the commencement of the official campaign period, a particularly significant development was the historic first-ever televised presidential debate that featured all three presidential candidates, followed shortly after by a similar event featuring the vice-presidential candidates. The presidential debate in particular attracted a high level of attention and coverage, and was lauded as according the electorate an opportunity to understand better the parties’ manifestos and plans.

Political parties and their supporters concluded their campaigns peacefully 48 hours before election day as stipulated by law.

5.4.1 Campaigning and campaign finance

Although the law provides for a campaign period of up to one month prior to election day, which was reduced to 21 days for this election, some political parties expressed a desire to reduce the amount of campaigning days further as a result of the high cost of campaigning.

The law also remains silent about the sources of campaign funding and does not specify limits on donations or expenditures. This undermines the equal opportunities principle of elections, and has ensured that the availability of finance constitutes a major factor in the political pro- cess. In essence, the wealthiest party possesses a significant advantage. The IEOM is of the view that there is a need for regulation on spending limits for political parties. The absence of such limits tilts the playing field in favour of those with more resources.

The flow of money into politics, if not appropriately regulated, has the potential to distort the will of the people and thus the integrity of the democratic process. In this regard, Somaliland’s legal framework suffers from two primary deficits: firstly, there is an inadequate normative framework regulating campaign finance; and secondly, there is extremely weak enforcement of existing legal safeguards. A robust funding regulation should include contribution limits, spending limits and mechanisms to monitor and impose penalties.

- Election day observations/assessment

6.1 Opening of polling stations

At the start of polling day, the IEOM observed opening procedures for 27 polling stations across Somaliland, in both rural and urban areas. The majority of the polling stations opened on time with a full contingent of polling personnel. Domestic observers and political party agents were present in all the polling stations visited during the opening. The polling stations were laid out in a manner that allowed easy flow of voter and maintenance of ballot confidentiality.

and voting procedures. The polling stations visited were generally peaceful with a few incidences of intrusive and intimidating behaviour by some of the party agents.

Some 92% of polling stations visited had all materials available by 6am. The IEOM was unable to ascertain the adequacy of quantities of materials because some of the polling officials did not follow procedure of taking stock of the received materials. Observers noted security presence outside most polling stations and described the se- curity as generally adequate and discreet.

6.2 Voting process