Enter and exit: everyday state practices at Somaliland’s Hargeisa Egal International Airport.

INTRODUCTION

I woke with a grunt when the wheels touched the runway. ‘So this is Somaliland and this is the airport that I will be studying the next couple of months’, I thought as I looked out of the window of the aircraft I had boarded a few hours earlier in Addis Ababa. I saw a few plane wrecks next to the airport building, and in the shade under one of the wings, I spotted a uniformed man drinking what looked like a cup of coffee.1

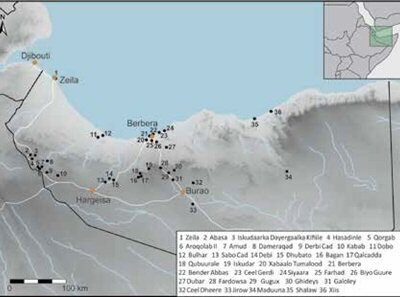

As this short excerpt from my field notes indicates, I literally landed in the middle of my research site, Hargeisa Egal International Airport (HEIA), when I first arrived in the unrecognised de facto state of Somaliland in March 2014.2 What had brought me to HEIA in the first place was curiosity about a rehabilitation project for the airport. The project meant that the runway was expanded and that a range of security practices and technologies were implemented during the period from 2012 to 2015 (Somalilandpress 2015). When I landed at HEIA I was interested in how an internationally unrecognised state was able to construct and develop an international airport, as well as in what such a rehabilitation project can reveal more generally about state formation. These interests are the focus of this working paper.

Somaliland broke away from the collapsed Democratic Republic in 1991 and despite, or maybe because of, limited external intervention, changing governments have been able to create and sustain accountable political institutions (Eubank 2012). In addition, subsequent governments, with support from international non- governmental organisations (NGOs), the European Union, the United Nations, and diasporic investors, have been able to build functional ministries and key state services such as infrastructure, health services, a school system and a police force (Kent et al. 2004; Menkhaus 2007; Kleist 2008; Lindley 2010; Ibrahim 2010; Hoehne

& Ibrahim 2014). In sum, as Hagmann and Hoehne (2009) argue, the Somaliland case illustrates that although the Somali state collapsed; the state and state practices re-emerged, albeit in a different shape.

In this paper, I highlight some of these emerging state practices in Somaliland empirically, by turning attention to state formation at the airport, a particular place in the state that is often ignored or overlooked. By airport practices, and emerging state practices, I refer to activities such as security checks, visa regulation, passport control and other types of activities where air travellers

interact with airport agents and procedures. My overall argument can be broken into two sub-arguments. On the one hand, my paper illustrates how emerging state practices at the airport are at once manifesting and anonymising Somaliland as a political entity, while at the same time being part of daily negotiations. On the other hand, my analysis demonstrates that different external resources and historical ties have been mobilised to rehabilitate the airport, highlighting how HEIA has become a site where the government of Somaliland seeks and finds international recognition. This two-sided analysis demonstrates that state formation is complex and imbued with contradictory processes that are contested and negotiated in everyday power relations.

Whereas the majority of studies of Somaliland’s state formation have focused on the central state apparatus and the interesting (hybrid) institutional set-up of the parliament (Bradbury 2008, Lewis 2008, Renders & Terlinden 2010, Hoehne 2011a, Hoehne 2013), I will in this paper turn attention to a border place of the state to provide a new perspective on state formation processes in Somaliland. In this paper the airport is viewed as a border place – as a place where the state begins and ends. Although the bulk of research on Somaliland focuses on the centre of the state, Hoehne (e.g. 2010 and 2015) has intensively studied the border region between Somaliland and Puntland in Somalia. The case of HEIA is a rather different type of border place as it is geographically closer to the heart of the Somaliland state administration and is arguably more important to the business people in the capital of Hargeisa than is the border region of Hoehne’s studies. The case of HEIA can, in this way, complement the research of border practices in Somaliland by unfolding practices that are closer to the state administration while at the same time being a gateway that connects Somaliland with the international community through a network of international airports. It should also be noticed that this study focuses mainly on security practices and the dynamics of interactions between airport agents and air travellers, and is less concerned with the range of other everyday practices that take place at HEIA such as the taxi trade, business meetings or parking regulations. In sum, the originality of this paper lies in analysing state formation as a series of nonlinear ongoing processes that are contested and negotiated through the everyday workings of an international airport located in an internationally unrecognised de facto state.

My analysis draws on empirical data collected during two months of fieldwork in Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland, in the spring of 2014. I conducted semi- structured interviews with state officials, elders, politicians, airport officials, practitioners and airport staff. In addition to primary data, I utilise literature on Somaliland’s political history as well as literature on airport practices and airport development to substantiate and discuss these bodies of literature with my empirical data.

The paper is divided into four sections followed by a conclusion. First I present some theoretical considerations about the approach to airport practices and everyday state formation that are used in this paper. Second, I present the history and changing functions of HEIA by locating HEIA in three key events in the established narrative of Somaliland’s state formation and through this explore the historical transformations of HEIA. The section shows not only the history of

HEIA, but also illustrates that the airport has been a central arena in the recent political history of Somaliland. In the third section, I examine more closely the security practices and technologies that emerged from the airport’s recent rehabilitation project. This is done to understand what the newly installed security technologies and practices mean for the constant (re)production of the state in Somaliland. The section also demonstrates that the state is manifesting itself while simultaneously becoming increasingly anonymised in day-to-day airport practices. Fourthly, I show in the last section how the renovation and upgrading of the airport was mobilised. On the one hand, I look into the norms and logics that were adopted by the airport management and state officials, and on the other I discuss the different actors involved in this process. Finally, I end the working paper by making some concluding remarks on how state formation proceeds in Somaliland from the perspective of HEIA.

2. AIRPORT PRACTICES AND EVERYDAY STATE FORMATION

As mentioned, airports are rarely the subject of studies of state formation. One of the exemptions is the brilliant work by Chalfin (2010). She researches the restructuring of state sovereignty through everyday practices of customs officials in a harbour, an airport, and at border post in Ghana. There is also a body of literature on airport geographies (see e.g. Creswell 2006; Salter 2005, 2006, and 2007; Adey 2004, 2008, and 2009), which focuses on airport security, mobility, and interactions between airport agents and travellers.

Obviously, airports have different characteristics to other state borders, for instance land borders. Airports serve a particular clientele who enter and exit the state by air (e.g. tourists and businessmen), whereas border places at the territorial edge of the state witness a different type of mobility, which again is accompanied by different sets of border practices (see also Chalfin 2010: 219–222).

The limited research on airports as analytical lenses is surprising as they exemplify state formation dynamics in at least two ways. First, airports are sites where mobility is highly regulated, where order has to be constantly (re)established and where state attempts to govern international mobility become visible. Second, airports represent border places that demarcate where the state ends and where it begins. Borders and boundaries have been a central theme in the work of many anthropologists. Barth argued that it is at the borders – in the meeting with ‘others’ – that ‘identity’ becomes visible (2000: 27–30). In analogy, the airport can be seen as a border place where the state can portray what it is not in relation to the international community and other nation states. Everyday practices at the airport – such as visa and passport control, body scanning, and tax collection – make airports objects of study that can enhance understanding of state formation.

My approach to state formation echoes Migdal and Schlichte’s (2005) call for scholars to cast aside normative assumptions about what the state should be and instead study how the state is constructed, reconstructed, invented and reinvented through a variety of practices and images by a multiplicity of actors. Thus, following the works of Hansen and Stepputat (2001), Olivier de Sardan (2008), and Hagmann and Péclard (2010), I propose to analyse state formation as ongoing processes that are constantly (re)produced and (re)constructed in everyday interactions in various arenas. In this regard, It is helpful to remind ourselves of Foucault’s (1991) observation, ‘the state is no more than a composite reality and mythicized abstraction, whose importance is a lot more limited than many of us think’ (ibid: 103). Foucault further argued that the state should not be understood as a central unity from where society is governed, rather he sees society as being

‘governmentalised’ through a variety of institutions, calculations and analyses (ibid: 102). Foucault thus reminds us that the state is a social construct that is constantly reproduced and remoulded through a variety of practices by a multiplicity of institutions and actors. Relatedly, Abrams (1988 [1977]) argued that the state is not a reality behind a mask of practices, but rather a mask itself that hinders us from viewing the political processes and institutions that construct the state. From this perspective, HEIA is a particular government institution that

constructs Somaliland as a state through the political practices by which it seeks to govern a particular part of the population.

More recently, Asad has argued that the state is concretised at its margins because, as he asserts, margins are ‘(…) places where state law and order continually have to be re-established’ (Asad 2004: 279). In fact, Asad points out, the abstract character of the state is what makes it possible to re-establish the state as one entity through a range of (administrative) practices (ibid: 281). The margin of the state should not necessarily be understood as the territorial edge of the state or as geographically distant to the central state power (i.e. the government), but rather the margin is best conceived by turning attention to the ‘(…) pervasive uncertainty of the law everywhere and to the arbitrariness of the authority that seeks to make law certain’ (ibid: 287). From this viewpoint the airport can be seen as a border site where the (abstract) state begins and where it ends, as mentioned above, and where authorities constantly need to make state law certain through a range of practices. It is important to notice that these practices are continuously contested and negotiated as Korf and Raeymaekers note (2013).

In connection, Feldman (2007) argues that airports are spaces where the entrance to the state is controlled, which make airports sites for strategic deployment of sovereignty. This idea echoes Adey’s (2008) argument that airports are spaces that differentiate and sort people, controlling mobility through various technologies. This means, as Chalfin (2010: 175–182) also argues, that airports are highly regulated, maybe more so than other border places, to secure certain types of mobility as well as to make certain types of mobility possible.

From these theoretical considerations, I will now move on to the political history of HEIA.

3. A POLITICAL HISTORY OF HARGEISA EGAL INTERNATIONAL

An inscription in the arrival terminal at HEIA commemorates that the Duke of Gloucester officially inaugurated the main building on 18 November 1958.3 The main airport building from 1958 is today a ruin, south of the runway, while today’s main buildings are located on the northern side of the runway. It is not clear when the airport was built. According to the Somaliland Ministry of Civil Aviation & Air Transport (MCAAT) it was constructed during World War II

(MCAAT 2012). Other sources suggest that it was established as a British military airport in 1954 (Louis Berger S.A. and Afro-Consult 2003: 7). During colonial times the airport mainly functioned as a gateway to Hargeisa for the British garrison. In the following, I look into the history of Hargeisa Airport through the prism of three particularly significant events that shaped Somaliland, involving the airport. Although other economic hubs in Somaliland, perhaps most significantly the port of Berbera, are economically more important to the political economy of Somaliland, the political history of HEIA is a particularly interesting window through which state formation processes in Somaliland can be analysed. As will be illustrated below, Hargeisa Airport played a crucial role at key political turning points of Somaliland’s history. The airport played a central military role in the bombing and destruction of Hargeisa in the late 1980s. Later, in the mid 1990s, the airport was a central arena in the new government’s attempt to consolidate state power and most recently HEIE has become a key instrument in the making a Somali trade hub in the Horn of Africa.

Hargeisa Airport in the post-colonial era

On 26 June 1960 British colonial rule officially ended and Somaliland was granted independence.4 The goal of uniting the five Somali regions; British Somaliland, Italian Somaliland, French Somaliland (Djibouti), Ogaden in Ethiopia, and north- eastern Kenya, was not possible. Instead, the former British Somaliland and former Italian Somaliland united and formed the Somali Democratic Republic (Samatar 1989: 79, Lewis 1980: 161). After a military coup in 1969, Mohamed Sayid Barre overthrew the democratically elected government of the Somali Democratic Republic and took over power. Although many in the north, as elsewhere in Somalia, supported the military rule of Barre in the beginning, this support eroded in the mid-1970s when the military and other state institutions were centralised in the capital of Mogadishu (Bradbury 2008: 58–60).

Unlike other regional airports in Somalia, Hargeisa Airport was not shut down in the early years of the Somali Republic, though all international flights ceased to service Hargeisa. Instead, the airport started to serve solely as a domestic airport

in the mid-1960s,5 indicating that the centralisation of state institutions started before Barre came to power. International flights were now strictly operating from the capital of Mogadishu and Berbera, the second largest city in the northern region. Hargeisa Airport was used as a connection point between Hargeisa and the capital, Mogadishu.6 However, this did not mean that Hargeisa Airport lost all of its importance for the Somali government, rather, its role changed. Located only 90 kilometres from the Ethiopian border, it later became a vital strategic military base for the Somali National Army in the Ethiopia–Somalia ‘Ogaden War’ of 1977 to 1978 (see Bradbury 2008: 38; Lewis, 1980: 231–235; or Tareke 2000: 635).

The Somali Democratic Republic lost the war, and soon after conflicts between the central government and various clan constituencies in Somalia escalated (Africa Watch 1990). This was also true for the Isaaq clan in the northern region of Somalia (what today is known as Somaliland) who felt increasingly marginalised. The defeat in the Ogaden War meant among other things that Isaaq clan members had limited access to grazing land (Van Brabant 1994: 11). In addition, goods were repeatedly confiscated at Berbera Port and khat farms were burned down across the northern region (Bradbury 2008: 59). The grievances with the Barre rule led to the formation of various rebel/liberation movements across the Somali Democratic Republic (see e.g. Kapteijns 2013). One of these was the ‘Somali National Movement’ (SNM), founded in London by the Somali diaspora (Bradbury 2008:

62). The SNM consisted mainly of people from the Isaaq clan (the largest clan family in today’s Somaliland), northern separatists and Islamists (Compagnon

1998; Gilkes 1993). The Ethiopian based ‘Western Somali Liberation Front’ (WSLF) operating in Ogaden, who received support from Somalia during the ‘Ogaden War’, was continuously supported by the Barre government, but this time to help the Somali National Army to force out high-ranking Isaaq clan members in the 1980s (Van Brabant 1994: 11–13).7 This meant that the conflicts between the SNM and the Barre regime escalated through the 1980s and in 1988 the SNM attacked Somali military positions in Burao and Hargeisa (Africa Watch 1990: 127–149). One of the SNM’s main targets was Hargeisa Airport (Gilkes 1989: 55).

On the ground, SNM took control of parts of Burao and Hargeisa in May 1988 and it took the Somali National Army several weeks to recover and relaunch an attack (Bradbury 2008: 60–63).8 The army launched its attack from Hargeisa Airport and bombed Hargeisa from the skies to force out the SNM troops. Although the SNM- led attacks failed to take over the airport (and other important military positions) it remains a ‘point of no return’ in the narrative about Somaliland. As one informant told me: ‘they [the army of the Somali Democratic Republic] tried to take control on land, but failed, so they bombed instead. This is why the airport is so important

– it must not get out of our hands’. In a 1989 briefing by Patrick Gilkes (1989: 55) from the Research and Information Centre of Eritrea, it was reported that the attacks resulted in approximately 50,000 casualties, while 400,000 Somalis fled the country (mainly to Ethiopia), and 1.5 million people were internally displaced. For many in Somaliland, especially in Burao and Hargeisa, these bombardments stand as a pivotal event in the making of Somaliland (see also Hoehne 2006). Today, on the main street in downtown Hargeisa, a Somali MiG fighter that was used to bombard the city in 1989 is displayed as a national monument to commemorate the attacks.

On one side of the monument the destruction of Hargeisa is displayed and on the other the liberation and (re)birth of Somaliland is portrayed. This is not to say that the SNM brought the downfall of the Barre regime, nor that this is the accurate account of what actually happened in the northern region of Somalia. Gilkes (1993: 7) argues that SNM played an insignificant role and that the reasons for the collapse of the Somali Republic should rather be found in the fighting in and around Mogadishu. The point here is that the airport plays a central role in the narrative about the making of Somaliland, and that it played a central role in

political and violent conflicts on several occasions.

Eventually, the Somali Republic collapsed and Somaliland declared its independence on 18 May 1991. At this point the airport was in a poor condition after years of civil war. After 1991 people slowly started to move back to Hargeisa and the Edgalle lineage of the Garhajis, an Isaaq sub-clan, began to resettle in the airport area where they had resided before the war. A clan militia that mainly consisted of Edagalle clan members took control of the airport after the Somali army retreated from the airport in 1991 (Gilkes 1995). This led to a major conflict between the new government of Somaliland led by the then President Mohamed Egal,10 who was elected after a peace conference in Borama in 1993 (Academy for Peace and Development 2015: 22), and Abdirahman Ahmed Ali ‘Tuur’, the predecessor of Egal. As will be demonstrated in the following, this conflict, also known as the ‘Airport War’ (Renders 2012: 126–140), was a milestone for President Egal as the outcome was a consolidation of state power.

The ‘Airport War’ and the consolidation of Somaliland

On 27 August 1994 President Mohamed Egal closed Hargeisa Airport, announcing that the airports in Berbera and Borama and a small strip in Kalabaydh had to be used instead (Gilkes 1995: 46). The announcement came after months of conflicts between the government of Somaliland and a clan militia known as ‘the third brigade’. President Egal had sought to nationalise and institutionalise various important revenue generators to obtain tax income to finance attempts to securitise and stabilise the Somaliland state. The nationalisation of the airport, however, was contested by the former SNM11 fighters of the ‘third brigade’ led by General Jama Mohamed Ghalib, which had controlled the airport and collected departure and landing fees from passengers since the collapse of the Somali Democratic Republic. The government attempted to negotiate with the militia and elders from the Edagalle clan to hand over the control of the airport to the government. On one occasion, a delegation of Edagalle elders were beaten up by the militia in an attempt to negotiate a solution, and negotiations broke down (Renders 2012: 129). The ‘Airport War’ erupted when the so-called ‘third brigade’ was forced out by government forces in October 1994 (ibid: 130). The militia fled to neighbouring areas where they once again, in November 1994, were attacked by the national army. This time the ‘third brigade’ retreated to the south of the city from where they launched smaller attacks on parts of the city. The ‘third brigade’ gradually gained support from parts of the government army and police force who were against Egal’s use of force (ibid: 131). This was partly because President Egal’s predecessor, Abdirahman Ahmed Ali ‘Tuur’, who belonged to the Habar Yoonis by clan,12 used the conflict between the government and the militia to

mobilise support against Egal. Conflicts between the government and different anti-government forces escalated in Hargeisa and fighting broke out in Burao in March 1995 as well. What started as a dispute between a militia and the government over the control of the airport developed into a political conflict between the government and supporters of ‘Tuur’, mainly belonging to the Habar Yoonis and Garhajis clans.

The main reason why people belonging to the Garhajis and Habar Yoonis clans became involved in the dispute was that they felt politically marginalised after former president ‘Tuur’ (from Habar Yoonis) lost the presidency to Egal (from Habar Awal) in the aforementioned Borama Conference of 1993 (Bryden & Farah 1996). The Airport War was therefore beset by the grievances of many Garhajis who felt that they had lost political power in Somaliland. Several of my Garhajis informants told me that the intervention of their clan relatives was more about political marginalisation than about seeking economic benefits from the airport.13 This resonates well with the observations by Matt Bryden (1994), a former observer attached to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) at the time, who reported that the ‘third brigade’ kept the airport fees to themselves. Bryden further reported that ‘Tuur’ supported a federal Somalia, which suggests that there were secessionist sentiments among ‘Tuur’ and his supporters. Thus, various political interests of different actors – some with anti-secessionist aims, others with economic interests in the airport, and others with aims of gaining political power, coincided in the build-up to the ‘Airport War’.

A United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) document reports that the ‘Airport War’ resulted in 90,000 new registered refugees in Ethiopia (Ambrose 2002: 7). Although the actual fighting ended in July 1996, it was not until the ‘Hargeisa Conference’ from October 1996 to February 1997 that peace was negotiated (Bradbury 2008: 127). The conference resulted in the two parties, representatives from the Garhajis clan on the one side and the Government of Somaliland on the other side, settling on a deal. The deal included the re-election of President Egal and further integration of Garhaijs clan members in the Guurti14 (the House of Representatives), ministries, and in the police force.

Balthasar (2013) argues that the ‘Airport War’ constituted a turning point for the Egal government as the confrontation and ensuing negotiations provided the Somaliland government and President Egal a unique opportunity for strengthening his position and shaping politics in Somaliland.15 Thus, in this early stage of the ‘new’ Somaliland, the airport was yet again a central arena. The Somaliland government re-appropriated the former government’s state buildings (i.e. the airport), thus state (re)building viewed from Hargeisa Airport took a literal form. The fact that the airport was later renamed Hargeisa Egal International Airport (HEIA) strongly symbolises the consolidation of the Somaliland state.

The making of a regional trade hub

The years after the civil war saw a steady increase of returnees from the diaspora as well as neighbouring refugee camps (Bradbury 2008: 160–163). The stability and increase of returnees also affected the airport, which saw a large increase in passenger traffic in these years (MCAAT 2012: 2).

In 1996 HEIA was primarily used for humanitarian flights and small commercial flights. Although the UNDP established a few basic services to ensure safe flights (UNDP 2012), the airport remained in poor condition throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The runway was rundown and the entire airport infrastructure was in serious need of renovation. In 2003 the airport averted closure by funding from UNDP that ensured basic patchwork of the runway (IRIN 2003). One of the larger projects in this period was the construction of the departure terminal, which meant that the airport now had two main buildings: one for arrivals and one for departures (ibid).16

By 2012 the airport was in desperate need of renovation and the Somaliland government initiated a large rehabilitation project to extend and fence the runway as well as to enhance the security inside the arrival and departure terminals (MCAAT 2012: 3). The project was finalised in 2015. The funding of these improvements came from a vast array of donors and investors such as the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development (Kuwait Fund), the United Kingdom’s Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO), and UNDP as already mentioned. Besides the Somaliland government, local businessmen and private companies such as Dahabshiil17 and Telesom18 contributed to the rehabilitation project (MNPD 2011: 121; MCAAT 2012) .19 These different sources of funding indicate that Somaliland is moving into regional and global trade networks, capital flows and economic exchanges, with ties to Arab Gulf states and different Western donors.

Although very little data exists on the development of aerial traffic to and from HEIA, official figures suggest that there has been an increase in commercial passengers of approximately 50% from 2009 to 2013 (MNPD 2013: 35).20 Today, the airport serves more than ten private airline companies, including Daallo Airlines, Jubba Airways, African Express, Ethiopian Airlines, FlyDubai and Fly-Sax as well as UN flights (MCAAT 2012: 2).21

The rehabilitation project was an integral part of a broader strategy of the Somaliland government. In the government of Somaliland’s 2011 ‘National Development Plan’ (NDP) infrastructural improvements are among the main objectives in achieving economic progress and reaching the Millennium

Development Goals (MNPD 2011: 1). In fact, the government of Somaliland claims

‘(…) infrastructure contributes to socio-economic and technological progress and thus is an issue of overarching importance to development’ (ibid: 29) and that they want a nation ’(…) interconnected and linked to neighbouring countries through a network of roads, railways, airports and seaports’ (ibid: 23). When I met the Minister of Trade & Investment, Omar Mohamed Omar, in a hotel lobby for a cup of coffee and a talk, he confirmed the official economic globalisation strategy described above. According to him, the aim of creating economic progress through ‘opening up’ to global markets is only possible if Hargeisa can be located within the aerial infrastructure of East Africa.22 He explained that one of the important means of doing so is by strengthening the economic connections to the Gulf States, specifically Dubai, and by creating a strong and reliable connection to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia.23 Similarly, when I asked an employee of MCAAT about the prospect of making HEIA a regional trade hub, he exclaimed ‘Hargeisa is the hub for Somali people. It used to be Djibouti, but now we are renovating it and making it more attractive and we have successfully become the hub of Somali people’.24 However, the rehabilitation project can also be viewed in light of the growing business sector in Hargeisa demanding better and safer aerial connections (see also The World Bank 2012).25 Furthermore, the airport rehabilitation project began the same year that Mogadishu Airport opened for international carriers from outside East Africa, when Turkish airlines started operating from Mogadishu (BBC 2012). This means that the rehabilitation should not be viewed as project driven by the government of Somaliland solely, but rather as a consequence of various actors’ interests in rehabilitating HEIA.

This short, political history of HEIA shows that changing political interests and shifting political constellations among a variety of actors have changed the functioning and architecture of the airport, illustrating the strength of unfolding state formation processes through airport histories.

4. Manifesting and Anonymising the State

This section dissects some of the security practices and technologies that were introduced during the airport rehabilitation of 2012 to 2015. Among the new technologies and practices introduced were: a fingerprint identification system, a closed circuit television system (CCTV), and a database system that registers and stores names and data of incoming and outgoing travellers.26 In addition, the Immigration Department staff at HEIA, mainly consisting of passport control and visa control officers, was trained.27 By looking into some of these practices and technologies, the argument in this section is that the Somaliland state manifests itself as day-to-day relations between airport agent and traveller are increasingly anonymised. Towards the end of this section I will also argue that these practices leave room for negotiating state practices, suggesting that state formation is negotiated on a daily basis.

Many of the technologies and practices introduced during the recent rehabilitation of HEIA were put in place to make aerial travel to and from the airport more secure. Fencing the runway, for instance, is one of the concrete measures implemented to secure in- and outgoing flights. Thus, airports and air travel are, as John Urry (2009: 28) claims, ‘sites of riskiness’ infused with ways of controlling these risks. Similarly, Adey (2009: 276) sees a close relationship between security and mobility by stating that: ‘(…) mobility has become a problematic of security as an object that needs securing’. Moreover, airport practices are, following Tim Cresswell’s (2006) argument, imbued with power and disciplinary activities that seek to regulate mobility. It is through this perspective that I will, in the following, interpret the security practices and technologies at HEIA.

‘The airport is the face of the country’

Before going into depth with visa regulations, surveillance mechanisms, and other security practices, I consider how these practices make the state legible to the air traveller in different ways. For example, the visa is a concrete way in which the state becomes visible to the individual. As illustrated in the picture of my own visa below, the application is stamped with the official logo of Somaliland’s immigration department, which along with the Somaliland flag and the airport agents’ uniform are clear symbols of the Somaliland state. Thus, practices such as the requirement for a visa and resulting procedures make the airport a site where the Somaliland state ‘(…) is represented and reproduced in visible everyday forms, such as language of legal practice, the architecture of public buildings, the wearing of military uniforms, or the marking out of policing of frontiers’ (Mitchell 1991: 81). This means that this ‘site of riskiness’ makes the state visible for the mobile traveller through a range of practices and images.

As I gradually gained access to the airport authorities in the course of my fieldwork, I realised that they also view the airport as a place where the state is

represented. The Operational Manager of HEIA told me that the airport is the ‘(…) mirror of the conditions of the state’.28 Similarly, on one of my tours around the airport I spoke with a young CCTV staff member who had just returned from security training in London. He told me ‘the airport is the face of the country, it is the first thing you see’.29 I asked him what he hoped people would see as the first thing, he replied ‘Somaliland has peace and stability and we want people to feel safe when they arrive. This is why security is so important to have here’.30 Building an airport is thus about more than paving a runway; it is also a space for constructing an image of Somaliland and the site where individual air travellers can see and encounter the (Somaliland) state.

Enter and exit: manifesting the state through ‘confessional rites’

During both arrival and departure travellers meet various airport agents, in particular passport controllers, tax collectors, visa controllers and guards. In addition, the traveller interacts with different technologies such as body scanners, a fingerprint identification scanner, and surveillance cameras.31 These interactions produce a range of data that are registered in databases by the immigration department under the Ministry of Interior.32 The data are stored by the immigration department, who thus have knowledge about visitors’ identities, as well as their purpose and duration of stay in the country. In other words, these security measures are practices that divide travellers in order for the state to know who enters and who exits the state (see Adey 2009: 277 for similar observations). Visa and passport controls are two specific tactics whereby facts about an individual are made legible for the state. Likewise, the copy of my visa application reveals my name, nationality, reason of stay, profession and passport number (which I have concealed here).

My encounter with the visa system made certain facts about me and my trip to Somaliland visible. In the same way, the passport reveals the traveller’s travel history, gender, and other facts. Thus, these practices transform the body ‘(…) into text so that it may be read’ (Adey 2004: 1371).

While the state becomes visible to the air travellers, as argued in the previous sections, the traveller also becomes visible to the state.

This observation of the recent transformation of HEIA echoes Louise Amoore’s

(2006) study of US border practices and her point that ‘(…) the subject becomes objectivised through a series of dividing practices which break up the subject into calculable risk factors both within herself (student, employee, tourist, man) and also in relation to others (alien, immigrant, illegal)’ (ibid: 339). Knowing an individual traveller’s history, identity, and reason for crossing the border are fundamental facts for airport agents to assess the risk of the moving individual. Moreover, these

overviewing practices are also part of the state’s logic to identify individuals within its territory.

The individual traveller needs to reveal bodily facts (gender, height, and so on) through visa processing and identity papers to the state to gain access to cross the state border (see also Salter 2006). Similarly, an airport consultant I interviewed articulated the importance of knowing the people entering Somaliland by air as:

‘(…) if we contain them, they won’t explode’.33 By ‘containing’ he referred to containing information about individuals in databases in order for the Ministry of Immigration to assess the risks inside its territory. These dividing practices, and the use of the word ‘explode’, should also be understood in light of the fear of anti-Somaliland groups such as Al Shabaab, which in 2008 launched the largest attack in Somaliland since the end of the civil war (‘Airport War’) in 1997 (BBC 2008).34

My observations from HEIA are in line with Mark Salter’s (2007) reflections on airports. Salter argues, by building on Foucault’s concept of the ‘confessionary complex’, that ‘[…] as travellers are conditioned to confess their history, intentions and identity, they submit to the examining power of the sovereign’ he continues ‘[…] confession is the toll of our entry into the political community’ (ibid: 59). Thus, crossing state/international borders activates a range of practices through which the

traveller confesses certain details about him/herself to airport agents. The encounters between traveller and airport agent can thus be described, building on Salter, as a ‘confessional rite’ that accompanies an individual’s crossing from international territory into the airport or from national territory into international space. Building on one of Salter’s (2005: 37–39) earlier arguments that international border crossings are based on ‘rites of passage’, it is easy to see how travellers have to enact certain rites to cross from one side of the border to the other. This involves a particular set of bodily gestures (e.g. taking off shoes before being scanned, putting fingers on scanner etc.) It is only by moving from one

‘confessional rite’ to the next, that travellers obtain permission to enter or exit the state. Scanning the moving body is one example of such a ‘confessional rite’.

‘Confessional rites’ are ways in which the state naturalises itself as an entity with the right to examine the individual (see Ferguson & Gupta, 2002), and in this way manifests the image of the state as the legitimate authority with the right to submit the individual to its examining power. My aim here is not to determine whether and to what degree these newly installed practices at HEIA are effective; rather, the point is, in the words of James Ferguson and Akhil Gupta (ibid: 981), that it is through these practices that the ‘state comes to be understood as a concrete, overarching, spatially encompassing reality’. Similarly to Chalfin’s (2008) findings from Ghana’s international airport, the HEIA case shows that by engaging in the various security technologies and practices – or confessional rites – the interactions between airport agents and travellers legitimise the state’s right to detect and register, overview, and divide individuals.

Negotiating airport practices: towards anonymised state power

Whereas I just argued that Somaliland is manifested as a concrete reality through various airport practices, I will now exemplify how these practices also reorient state power by making interactions increasingly anonymised. The following example from the ‘security building’, which is an annex that all travellers and personnel go through before entering the departure terminal, aptly illustrates this point.35 On one afternoon, I was invited to meet the Minister of the Interior in the airport’s VIP lounge. A security guard who would bring my friend and I through the security building waited for us at the door:

[…] we went into the security building. The security guard would bring us through the security check. At first, the security guard wanted to walk around the scanner, but he was not allowed to by the airport agent standing at the body scanner. When he realised he had to walk through the scanner he became very upset. However, the airport agent at the security machine calmly let him know that the rules applied to all going through the security building, as my gatekeeper later translated for me. He threw his walkie-talkie and other belongings into the tray on the conveyer belt leading into the baggage scanner and walked while loudly protesting through the body scanner. He was by no means trying to hide his dissatisfaction with the situation.36

Whereas interactions between traveller and airport security were previously a relation between persons involving a manual pat down, this new type of security interaction is preformed through machines, allowing airport staff to take a less central position (see Chalfin 2010: 158–186 for a similar type of observation at Tema Harbour in Ghana). Thus, the newly installed scanners transform the type of relationship between airport agent and individual traveller towards a more anonymised type of security practice. The fingerprint registration is another example of this trend. However, the increasing use of technology and anonymisation of state power does not mean that there is no room to negotiate the security practices as the above vignette also illustrates. Similarly to Chalfin’s

(2008) findings from Ghana’s international airport, the excerpt above also illustrates that the room to negotiate everyday relations continues or even increases, despite the introduction of new security norms and technologies. In HEIE these negotiation processes occur on different levels. For instance, when I travelled from Hargeisa to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia in the spring of 2014 I witnessed that Ethiopian Airlines use their own staff to make an additional search of travellers’ hand luggage before entering the their aircraft.37 I was also told stories about how people are treated very differently at the airport depending on their social, economic and political status. For instance, ministers and other powerful people do not necessarily have to get their luggage scanned and they are allowed to walk around the body scanner.38 I observed a similar case one afternoon when I went to the airport with a friend who had promised to drive his relatives to the airport. As a general rule only departing travellers and airport staff are allowed to enter the airport’s remade departure terminal. My friend wanted to enter the departure terminal to see off his relatives just before they began their flight. At first he was denied access to the departure terminal by airport guards. However, it only took him a couple of phone calls to a friend working in the airport to obtain access to enter the departure terminal.39 These observations suggest that although power relations at the airport are becoming increasingly anonymised through the introduction of various technologies promoted by the Somaliland government, there is still room to negotiate their particular uses and application.

5.‘We have to look just like other airports’: State Formation BY

This last section focuses on a different aspect of state formation by looking into the strategies deployed by the state officials, and airport management to mobilise external resources for the rehabilitation project. Firstly, I unfold ways in which the airport management and state officials rationalise the introduction of the rehabilitation project. Secondly, I illustrate how various actors mobilise the recently installed airport practices and technologies. These two parts both reveal the strategies through which state formation in Somaliland proceeds, taking HEIA as an entry point. The main argument here is that airport and state officials have internalised international norms of airport practices and make use of various external alliances and ties. The rehabilitation of HEIA thus proceeded by what Bayart (2000: 218) has coined a strategy of ‘extraversion’, meaning by ‘mobilizing resources derived from their [states’ or government’s] (possibly unequal) relationship with the external environment’.

The example of HEIA suggests that current state formation in Somaliland is characterised by an outward approach to state building and an instrumental way of using external opportunities. It is important to notice that earlier state building in Somaliland did not proceed through strategies of extraversion.40 On the contrary, earlier state building attempts in Somaliland are better characterised by the lack of external support and intervention (see e.g. Eubank 2010). Furthermore, this section demonstrates that Somaliland’s claim for the international recognition of its state sovereignty is not solely restricted to the diplomatic sphere of international relations, but relocates itself into other arenas of recognition seeking.

Rehabilitation through competition and privatisation

Soon after I started my initial inquiry on the rehabilitation of HEIA, I realised that the airport management and state officials closely relate to international airport norms stemming from the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). The ICAO is an agency under the United Nations (UN) and whose objectives are ‘(…) to develop the principles and techniques of international air navigation and to foster the planning and development of international air transport’ (Mackenzie 2010: IX). To this end ICAO is involved in the ‘development of airways, airports, and air navigation’ (ibid). When I met a high-ranking employee of MCAAT he explained me how the ICAO standards mirror the ways in which he envisions the future of the airport:

When we took the power of civil aviation. We were in category 2 in the ICAO standard, now we are category 7. We have moved five steps in the limited time of three years. The next year we hope to move to category 10; in the same category as Nairobi and Addis Ababa […] this is our milestone within a limited time.41

The statement of the employee shows that the HEIA management describes its goals for the airport development in competitive terms and in relation to other international airports in the region. The rehabilitation of the airport thus has to be understood in a broader framework of global airport competition. This resonates well with Jean-Paul Addie’s (2014: 96) argument that ‘[…] competition between air hubs is being framed at the global level, while the discourse and practices of airport governance clearly internalize the logics of globalized economic competitiveness’. The airport manager similarly referred to the competition among international airports when he told me that he wants HEIA to: ‘[…] look like other large modern airports’.42 He added:

The future goal is that we are recognised [acknowledged internationally as a good airport]: we have to connect to other airports; we have to look just like other airports, like in Nairobi, Addis and so on. I go around to relate to other airports and see how they do it: that is why I was in Djibouti recently.43

The logic of competition and climbing up the ranking of the ICAO categories was also a central topic in a conversation I had with a legal advisor to MCAAT. When I asked about his future dream for the airport he answered, ‘ICAO categorises airports. The dream is to move up in these categories’.44 His answer perfectly illustrates the competitive logic embraced by the HEIA authorities and management. The dreams and aspirations of HEIA managers attest to their internalisation of the neoliberal logic of airport competition. Competitive positioning in order to improve one’s ranking by the ICAO is not particular to HEIA. Cynthia Akwei et al. (2012) studied the performance measurements of Kotoka Airport in Ghana, 45 concluding that the airport: ‘[…] meet[s] the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) standards [to] enhance their competitiveness and profitability’ (ibid: 538). Participating in international airport competition, privatisation and commercialisation is thus a recurrent feature of airport improvements worldwide as the case of HEIA similarly demonstrates.

The logic of privatisation is most evident in the collection of exit fees and the general luggage handling at HEIA. A private company called National Airport Services and Ground Handling Agent (NASHA) manages luggage check-in and handles incoming luggage. In addition, NASHA collects exit fees, which are spent on maintenance and upgrading of their equipment. 46 Another example is the proposed privatisation of the MCAAT (MNPD 2011: 119).47 The plan is to establish a technical body separate from the government, which according to MCAAT and the Ministry of Trade and Investments (MTI) will create a more efficient airport authority. This point was made clear to me by the Minister of MTI:

An airport should be managed by an independent body. Government should be represented, but we should have a Somaliland Aviation Authority and not a Ministry of

Aviation […] Governments and ministries make policies; they should not govern airports, an agency should do this – it is more efficient.48

It is important to mention that other agencies in Somaliland’s infrastructural network have become autonomous under the government of Somaliland, most notably Berbera Port Authority and the Road Development Authority (MNPD 2011: 102–106).49 Thus, the creation of a private aviation authority is part of a broader rationale of decentralising the management of Somaliland’s infrastructure. Interestingly, this occurs through ideas of outsourcing state capacities to non-state actors (see Chalfin 2010: 185–186 for similar observations in Ghana).

Mobilising external ties and international experts

As mentioned above, I met the Somaliland Minister of the Interior Ali Mohamed Waran Ade in the airport lounge, where pictures of Somaliland’s former presidents decorate the walls alongside large Somaliland flags. We were served a cup of sweet Somali tea as the minister began his story about his close ties with a family member of the monarch. His friendship was very helpful in funding the airport reformation projects, he told me. He elaborated and said that the monarchy has several houses and farms in Somalia and Somaliland – among these a house in Sheikh, a city in the north of Somaliland.50 According to the minister, he personally showed the family member of the monarch the poor conditions of the runway. ‘[…] ‘look, we need to rebuild this’’51 he reportedly said to him, and he further told me ‘I wrote a letter to the king. I wrote: “you used to love Somaliland, now we need your help to rebuild our airports” ’.52 I cannot confirm whether the minister’s relationship with the monarchy is as close as he claims, rather the point I gained from my conversation with the minister is that Somaliland’s officials used historical ties and international opportunities to mobilise finances for airport rehabilitation. In an interview I conducted with an employee of MCAAT in his office in Hargeisa, he too elaborated on the monarchy’s interest in improving Somaliland’s infrastructure.

The family like wild[life] and hunting, so they want to come to our country and hunt. They want a place to sit down and settle. There is a town here called Sheikh. It is a good place, very beautiful; they constructed a three million house there. They also constructed a million dollar house with space for boats. Whatever we need we request […] they are good people.53

The quote above shows that close ties with the monarch were brought into play – one way or another – to help facilitate the upgrading of the airport. Ties to the

Japanese government and the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office were utilised as well (MCAAT 2012: 3). An airport consultant helped me immensely by showing me around the airport. On one of these tours, the consultant told me that the UK interest in professionalising the security at HEIA started when the threat of terror increased in London prior to the Olympic Games in 2012:

The airport security project supervised by ASI is due to national British interests: people are not screened well here in Somaliland and the UK government is afraid of the threat of terror in UK by Somalis coming to UK through, for example, Hargeisa, so they want to enhance the level of security in Somaliland.54

British interest in strengthening HEIA’s security dispositive had been mentioned to me a couple of weeks earlier by a UN employee in Hargeisa who also told me that UNDP had pushed for security upgrades well before 2012.55 Thus, UK government funding should be viewed as part of the UK government’s interest in securing its own territory against terrorist attacks by strengthening border control overseas (see also UK Government 2011: 44–56; UK Government 2010: 28–29).56 This demonstrates that the Somaliland authorities actively used external resources and historical ties and in this way made use of their relation of dependence (with the former British colonisers) productive – what Bayart (2000) termed

‘extraversion’. This point was further evident from the talk I had with the legal advisor at MCAAT, who explained how the airport was financed with help from Somaliland’s historical ties to Arab Gulf states and the UK.

Somaliland returned to the monarchy for funding the extension of the runway. And [we asked] UK, our old masters: please, help us now big man [laughing]. For help they provided security by Adam Smith International, who became the contractor of setting up the security system.57

HEIA rehabilitation was made possible by pooling private, public, local, national and international funding and donors. Not only did international actors play a key role in providing finances, the international dimension is also important when looking at the daily work of construction workers and airport agents. For example, the local contractor Daryeel Construction Company (Daryeel) carried out the day- to-day construction work of extending the runway and fencing the airport area under the supervision of Dr Nabeel Abdul-Raheem Consultants (NARCO). NARCO is an international engineering consultancy with projects around the world in various areas of infrastructural engineering.58 In the NARCO office in Hargeisa, I met asked an engineer how they supervise workers:

First, we check what needs to be done, then we tell the contractor [Daryeel] what to do and then we come back: approve or tell them to change it. […] We follow the ICAO specifications. For instance, the shoulders need to have a certain width to be able to receive

certain flights […] the standards tell us how to do excavation, levelling, and how to do the actual constructions.59

This excerpt above highlights the importance of ICAO’s international standards in airport rehabilitation and, more broadly, state formation. ICAO standards determine the width of the apron and how long the runway and fencing have to be to enable certain types of airplanes to land and take off. Even the type and size of the stones used for the specific type of renovation of the runway is conducted in accordance with particular agreed-upon international standards.60 NARCO is thus the actor that translates international technical standards prescribed by ICAO into the reality of the various construction sites at HEIA.

Similar dynamics are found in the implementation of security mechanisms inside the airport. A group of experts from the International Organisation of Migration (IOM) and Adam Smith International (ASI), which provide national security strategies, was hired to supervise and manage the implementation of the security standards and security machines.61 An example of this, are the so called ‘exposure tours’, where personnel from the immigration department learned about ‘good practices’ of border control in the UK.62

The central role that various international expert organisations played in the process illustrates that the rehabilitation of HEIA is embedded within a global assemblage of security practices and (private) security actors (see also Abrahamsen & Williams 2011).

6. Conclusion

This working paper illustrates that airports are fascinating windows through which state formation processes can be investigated. It highlights that airports are intrinsic parts of state building in very concrete ways and reminds us that state formation processes are permeated with contradictions. The main aims of this paper were to analyse how an unrecognised state builds and develops an internationally recognised airport, as well as investigating what this means for processes of state formation.

Beginning with the latter, the paper demonstrates that the newly installed practices at HEIA manifest the Somaliland state through what I call ‘confessional rites’ whereby air travellers engage in rituals with airport agents and technologies for the travellers to be granted acceptance to enter or exit the state. This means, more precisely, that to regulate mobility bodily and personal facts about the traveller are put to the fore and hence make the individual knowable to the state. These practices at the airport are manifesting an image of the state as an overarching authority with the exceptional right to examine and regulate people moving through its territory. It is through these mundane measures that the

‘abstract state’ is concretised and comes to be understood as a spatially encompassing reality as Ferguson and Gupta (2002) put it. However, as illustrated with empirical material from HEIA, the technologies at the same time recast interpersonal relations and seek to create more anonymous types of power relations. This, however, does not mean that there is less room to negotiate these practices. Thus, the emerging state practices in HEIA demonstrate well that state formation is neither linear nor harmonious; instead works in ongoing and paradoxical processes negotiated in everyday interactions.

In relation to recognition, the working paper shows that the HEIA management and Somaliland state officials have internalised international norms of airport management and security practices stemming from ICAO. The quote ’we have to look just like other airports’ encapsulates HEIA’s aspiration of living up to international airport norms of airport development. It thus becomes evident that HEIA has become a site for Somaliland’s quest for international recognition beyond official channels of bilateral and multilateral diplomacy. In other words, by mobilising international norms and external actors, the airport management and Somaliland state officials seek and obtain recognition by transforming HEIA into an internationally recognised airport. This means, in other words, that state recognition cannot be analogised with a switch that is either turned on or off, rather recognition comes in pieces and parcels that can be lost and gained.

By TOBIAS GANDRUP