Xeer Somaliland

Xeer – the Somali customary law as a tool of the alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanism in Somaliland

‘The Somali legal system greatly resembles the Internet. Like over the Internet, nobody exercises power over it. (…) Every Somalian can join it as a judge, policeman, guarantor, legal counsel or the person seeking justice.’ (statement of an interlocutor from Hargeisa)

Somaliland – a silent partnership with the international community

The Republic of Somaliland, located in the Horn of Africa, until now has not received formal international recognition at the United Nations. However, the Somali Constitutionalists repeat like a mantra that the political fact of the functioning of a state does not depend on its recognition by other states. Adherents of the international recognition of a new African state constantly refer in their argumentation to Article 3 of the Convention from Montevideo of 26 December 1933, which did not consider the recognition of other states as the prerequisite of the state subjectivity. Somaliland has a constant population, defined territory, sovereign power and the ability to establish international relations.

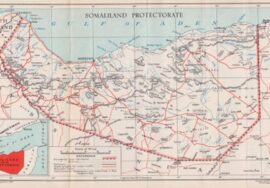

The population of Somaliland amounts to 3 million, of which 55% are nomads, whereas 43% of the population lives in towns and villages. The territory of Somaliland overlaps the colonial borders of the British Somaliland Protectorate, which functioned in the years 1884 – 1940 and 1940 – 1960. Borders are protected by the state authorities and the entry into the territory requires obtaining an entry visa from the foreign representative office. The parliamentary system meets the requirements of the tripartite separation of powers into judiciary, legislative (Senior Council and Representative chamber), and executive one (presidential system, where members of the Council of Ministers are appointed by the President. Ministers are not allowed to combine their ministerial functions with their seat in the Parliament). Somaliland took over the international obligations of Somalia and recognised all conventions whose party was Somaliland. In the territory of Somaliland function international organisations, including the United Nations (UN), with which Somaliland concluded a series of international agreements. Within the realm of bilateral relations, in March 2016, Somaliland concluded an intergovernmental agreement with Ethiopia concerning the use of the seaport in Berbera. These examples prove the recognition of de facto the ability to conclude international agreements by this country. The political experience of Somaliland and its elites in shaping international relations has its roots in the colonial politics of Great Britain, which in 1884 established its protectorate in the Horn of Africa, which lasted until July 1, 1960. During the period before the adoption of Islam in the Horn of Africa, according to the oral tradition, the system of customary law xeer was formed, which could be a way of leading to the settlement in the civil war-torn Somalia.

British Colonial Administration was governed by pragmatism in order to secure imperial interests and did not interfere with internal social relations if they did not pose a threat to the Empire. Clan elders Issak (the main tribe in Somaliland) represented the principle of ancestral selfishness and as the political elite they did not sustain a loss on their authority by intervening in negotiations on seizing power. Many participants of this process found shelter in Great Britain as refugees fleeing from persecution by the regime of Siade Barre within the period of compulsory unification with Italian Somalia within the so called Somali Democratic Republic. Tragic experience from this period had a big impact on the effectiveness of techniques of functioning of power in exile and the consolidation of Issak clans towards the idea of independence as the best form of securing own ancestral interests.

The period of persecution, including mass resettlements, is linked to the forced introduction in Somalia the principles of the ‘scientific socialism’. The period of unlawfulness and chaos

stemming from the escalation of the Somali Civil War in the years 1988-1991 deepened the traditional gulf between waqooyi (the North) and the remaining part of the former Italian Somalia, defined as koonfur (the South). The stabilising factor in the region hit by tribal fights became traditional ancestral bonds and the system of the ‘living customary law’ as a tool to resolve disputes.

Muhammed Haji Ibrahim Egal, the second President of the proclaimed Republic of Somaliland, in the period between 16 May 1993 and 3 May 2002, fell prey to the communist repression and traditionalists in support of the customary law system. Undoubtedly, thanks to his sturdy character in the period of persecution he received acclaim among the clan elders of Somaliland. His main asset was the fact that as the Prime Minister of Somalia in the 1960s he demonstrated experience and knowledge necessary to exercise such power. As a result, he was designated by the Council of Elders to be the head of the state, which split off from Somalia in 1991. The exit of Somaliland from the State Union with Somalia took place at the Congress of the clan’s elders, held between April 27 and May 15, 1991 in Burao. Separation of Somaliland followed the decision taken by the Council of the Elders to reinstate the borders and law of the former British Protectorate. The re-try of this state to come into existence as a subject of international law rested upon the assumption of the right of peoples to self-determination. The political decision on secession was taken by the Council of Elder Clans. The date of gaining independence became the national holiday in Somaliland. The day of re-gaining independence is an opportunity to demonstrate distinctiveness in relation to Somalia, which, contrary to Somaliland, enjoys full recognition of the UN with borders from before 18 May 1991. Peter J. Schraeder, an American political scientist, published a paper supporting rationale for the statehood of Somaliland. The author states that one should not omit the fact that this country had already been recognised by the international community in July 1960. The acknowledgement was declared by the United States within the group of 35 states being the members of the UN. Several days later, on 1 July 1960, Somaliland, linked to London by colonial ties, acceded the state union with the Trust Territory of the UN, which was previously under the administration of fascist Italy.

The formation of an independent state and a new nation rooted in the tradition of Issak clans is the result of the evolutionary process: the organic transition from the world of values of the pastoral culture towards the nailed model of the state power shaped by the pastoral tradition and trans-national nomadism.

Positive law, Sharia law, customary law xeer

In Somali communities in the Horn of Africa the same legal case may be considered from the perspective of various mechanisms defined by positive law, Sharia law or customary law xeer. The problem concerning the collision of legal norms in the context of the state order and the choice of appropriate law is solved by Article 130 of the Somaliland Constitution, which stipulates that the code clauses incompatible with the civil rights and freedoms, and Sharia law should be omitted when applying law.

On the level of positive, substantive criminal law in Somaliland applies the Somali Criminal Code of 1930 adopted in the fascist Italy. In its time, it was considered the modern legislative model to follow. In accordance with the explanations from the interview with Berihu Tewelde Birhan Gebre Selassie, the vice-president of the Ethiopia’s Supreme Court, the history of the criminal law in Somaliland is closely linked to the influence of the colonial states: Great Britain and Italy. The codifications from the times of dependency on London and Rome remain in force until today. The impact of Italian substantive criminal law was petrified in the whole Somalia after World War II through the reception of this law within the UN Trust Territory. The merger of Somaliland with this territory was followed by the reception of the Italian model of criminal law in the whole territory of former Somalia.

According to the tradition and constitution, the superior source of law in Somaliland are the

‘principles of Islam contained in the Koran, Muslim tradition (Hadith) and accounts of the Prophet Muhammad’s life (Sunna)’. Faith in the divine origin and revelation of law (fiqh) endows them with the highest authority. Secular positive law can regulate issues not mentioned in the Koran or can be constituted by virtue of such a provision which allows for the dynamic

interpretation of the norm. On that basis, Muslim law was developed by the jurists from schools of law, whose binding interpretations are applied in jurisdiction.

The rule of thought of such Sharia legal principle not subject to the interpretation is applied, for example, in ruling in cases regarding homosexuality where the sexual intercourse (adultery) between people of the same sex is punished by imprisonment from three months to three years (Article 409 of The Somali Criminal Code. Islamic law enumerates: adultery (punished in Somaliland by imprisonment to two years, Article 426 Criminal Code of Somaliland, false accusation of adultery (punished pursuant to Article 451 Criminal Code of Somaliland enabling the judge to rule up to ten years of imprisonment), drinking wine (penalty of detention to four months or a fine, Article 412 Criminal Code of Somaliland), theft and mugging punished in

Somaliland on the basis of Article 480 pursuant to Article 481 Criminal Code of Somaliland with imprisonment from one year to six years as offences strictly punishable in public by the secular authorities. Common courts of law in civil and family cases comply with the prior decisions of the tribal elders. Judges rule independently from the influence of the elders only in cases of criminal offences against the activities of the public administration or the secular judiciary of Somaliland.

The Shafi’i, who for centuries have shaped the tradition of Muslim law in Somalia refer to the legal interpretation of their master Al-Shafi’i, famous for his moderation and eagerly referring to the analogy (qiyas) and universal consensus (ijma’). The Shafi’i in Somalia and Djibouti ascribe great significance to the principle of universal consensus – in fact the consensus of the Muslim community is to come from God – and its purpose is to strengthen the unity of believers. The Shafi’i managed to organise numerous legal precedents as a result of which Muslim law in Somalia is characterised by traditionalism, and simultaneously by rationalism based on logical jurisprudence.

In disputable matters, often associated with the damage to the person or property, in Somaliland is primarily applied the traditional system of customary law – adat, based on the consensus principle of the Muslim community. Adat (local customary practice) is a normative system stemming from the Arabic tribal traditions and understood as ‘customary law functioning within some Sharia schools in Muslim countries, mainly in Malay, Indonesia and Central Asia, but also in Maghreb (known there also as urf)1. It is mostly prevalent in the countries and communities that are superficially Islamised. Initially, adat constituted a component part of Muslim law, and later it was applied to cases to which Sharia did not respond. Adat is at fullest recognised by the Hanafi and Shafi’i school of law, and almost completely rejected by the Hanbali’. Pursuant to the definition adopted by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO): ‘customary law is the collection of customs, generally adopted code of conduct, convictions adopted as compulsory principles of procedure by indigenous inhabitants and local communities’. Customary law is for the Somalis the tool of individual protection as well as the tradition and knowledge passed on from generation to generation. In the context of social relations, customary law offers an effective and cheap instrument to settle disputes, guaranteeing an imminent application of sanctions in the event of breach of the code of conduct.

The organic nature of customary law and its autonomy is put by this system in opposition to the norms promulgated by the state or religious authority. Kadirijjia, the traditional Sufi brotherhood, which has a significant influence on the interpretation of customs of the xeer system in the Horn of Africa, was the target of attacks of new radical groups, like for example saalhija – associated with Saij Muammad ibn’ Abdil Hassan, called in the British historical sources ‘Crazy Mullah’ fighting with their protectorate, or contemporary terrorist group Al Shabaab.

In the Horn of Africa, adherents of the religious movement of Wahabis financed by the Saudi Arabia support the orthodox Sharia directly referring to the Koranic traditions. In the areas of Somalia controlled by Al-Shabaab applies the absolute Sharia law, prohibiting the application of customary law. The prohibition of using drugs, by analogy (in Muslim law: qiyas) concerning the ban on drinking wine contained in Koran (Koran 7:80-84), is not respected in Somaliland where the influence of Koranic school of Wahabis is officially limited. Somaliland has adopted the interpretation which translates the role of tradition and custom in connection with the norms included in the Koran. The lawyer in Hargeisa explains:

‘If such a customary social norm was shaped later than the Koran, then it has a higher legal significance than the law of sharia in order to preserve the consensus in the local Muslim community accordant with the will of Allah’.

The practice of applying customary law is illustrated by the dilatation of the ulema, Muslim theologians having an impact on the religious code formed according to the Koran as regards legalising the custom of chewing gum in Somaliland prohibited by the law of sharia. Catha edulis (khat), being a mild stimulator or a drug, is here thanks to this interpretation widely available as a stimulant both for men and women. Ijma’, or the unanimous order of the scholars in law, allowed for the desertion from the law of sharia and exclusion of this drug from the religious, sharia prohibition of consumption. Moreover, the ulema in Somaliland explain that chewing leaves of this plant leads to greater concentration while reading the Koran and praying. A similar interpretation was also adopted in Yemen. The Hanbali, from the most conservative school of law of the Sunni Islam, currently in Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and in Kuwait, prohibit categorically the cultivation, trade and the consumption of khat.

Ioan Myrddin Lewis, a British researcher of the social structure of Somalia and shamanism points to the archaic sources of customary law in the Horn of Africa, referring to the type of culture which has evolved in the climate prevailing there and geographical conditions. According to the findings of this anthropologist, in the traditionally pastoral Somali societies

pastures were not covered by the title of ownership. The right to grazing was related to the actual possession of control over the pasture. According to the adopted rule, pastures are the gift from God and man only has the right to benefit from this good. The right of access to the well was, however, assignable and protected with the use of power of its holder. The formation of the structure of norms resulted from the collective attitude to the practical functions of coexistence and the principles of nomadic pastoral economy.

In Somaliland, even in the time of Lewis research, customary law was developing among the largest and strongest there Issak clan. This process is being pursued after gaining independence by Somaliland, contributing to the consolidation of social peace, as opposed to the remaining regions of Somalia. Following Stéphan Voell, a German anthropologist, referring to the example of the Albanian customary law kanun, it may be assumed that the stabilising value of customary law has been proven: it supports more effectively than the religious and positive law

the difficult process of regeneration of social bonds and organisations after historically difficult

periods of the past revolutionary social experiments or contemporary humanitarian interventions.

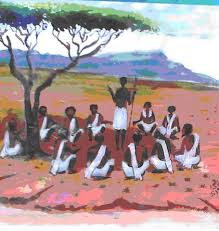

Xeer as a tool for resolving disputes

Xeer, a culturally defined system of folklore and habits (habitus), is subject to the international protection under the provisions of the convention of 1992 on biodiversity. In the Somali language, the word xeer means the consensus between the entitled groups having the ability to redeem themselves from the revenge of a bloody foreteller. The word diye is an Arabic synonym for the Somali expression mag, which signifies the redemption of the lineage from the threat of a bloody revenge. Each group having the ability to pay mag possesses its own, handed over from generation to generation, code of customary norms embracing subjectively only members of the clan (tol). Initially rooted in nomadism, system of norms referred to the grazing of camels, access to the well with water for shepherds and their animals. Xeer may also be understood as a process of mediation (masalaxo), or even arbitration (gar dawe).

The need to counteract, on the basis of xeer, the bloody revenge and the principle of talion is a customary law principle, ‘according to which the criminal act (especially murder) committed by a member of one group on another group member of the same society gives rise to a social

relation based on reciprocal murderous hostility (‘being in blood’) and is subject to the sunction of a direct bloody retribution’, and is the achievement of the ancestral-tribal culture of the Somali shepherds.

In the event of death caused by an act or the omission by a clan member, the system mag – diye (equivalent to the institution of were-gild and compensatory damages in the early medieval law, written down in the capitulars of Franconian kings) is applied, obliging to pay the compensation fixed by the elders of the clan negotiating an amicable adjustment of the case. Norms of mag – diye are universal in the whole community and belong to the repertory xeer guud, respected in all communities and regions.

These norms are rooted in the pastoral culture of nomads who did not resort to the acts of violence when fighting for watering holes and the right to use pastures for their herds. The mechanism of amicable adjustment of disputes became the basis of the customary law, which has survived all crises of the contemporary Somali statehood. In the Muslim law of the Sunni tradition, consensus is one of the key tools of the Islam jurisprudence Islam. Traditional customary law xeer has never been codified and there are no existing written studies of this jurisdiction. The knowledge of traditions and principles of legal logic passed orally from generation to generation is of key importance here. Opponents of the customary law xeer were the Somali communists trained in the Soviet Union and contemporary jihadists from Al Shabaab or Wahhabis based on the Hanbali from the thought collective of the most conservative Muslim lawyers.

However, this does not mean that the judgments issued are based on arbitrary decisions of the judges. The nature of the ruling – settlement is based on the amicable adjustment of disputes, but the compromise is rigorously enforced. Somalis who apply xeer are not so much interested in establishing the suspect’s guilt or innocence – it is important to reach consensus (win-win situation). All participants of a dispute have to abandon it without ‘losing face’ and a sense of adequacy of a sanction being the inconvenience for the whole clan. Guardians of the tradition of customary law are members of the clan elders, distinguishing themselves by knowledge and trust (xeer begti). The conclusion of a settlement between clans in cases of murder ends the case only after the payment of the mag – diye compensation. Compensation for the death of a man means the need to pay damages equal to the market equivalent of 100 camels, whereas for the murder of a woman was determined at the market value of 50 camels. The diya-mag compensation is currently paid primarily in criminal cases (dhiig) for slander, theft, personal injury, rape or murder.

The principles of customary law xeer assume the principle of collective responsibility of the

clan as part of the obligation to compensate for the waiver of a bloody revenge relating to all

male, adult members of the clan (mag – diye payment). Under this system special protection

was given to the elderly people, women respecting the principles of Sharia, children, poets and

Special messengers, who are to initiate the negotiation process, are treated with due

respect, which guarantees them personal immunity. The murder case in Somaliland can be run

on the basis of a criminal procedure before a state court applying the legal norms contained in

the Criminal Code. The conclusion of an out-of-court settlement in the ordinary course of

customary law xeer is a prerequisite for the quashing of legal proceedings, and even without a

ruling on guilt and punishment. A traditional settlement between clans offering damages to the

injured is a more popular way of seeking justice. A court judgment may encounter obstacles to

its execution or enforcement. The state does not have at its disposal due force of constraint, like

the one guaranteed by the strength of tradition, although there is a prison in Somaliland visited

by the United Nations, where convicted pirates, or foreigners-strangers serve a sentence of

imprisonment ruled in the common court on the basis of legal norms of positive law. There are

also those affected by the ostracism for the notorious violations of legal order and members of

the families, unworthy of protection, for whom the tradition of the clan arbitration xeer did not

stand in practice.

Xeer system also regulates civil torts (dhaqan) and contains a useful for this jurisdiction

gradation of offence presented on a 12-grade scale measuring the scope of cause related to an injury. The amount of a compensation can be marked, taking into consideration the wealth of the clan and the circumstances of the case. This is a manifestation of recognition of caste system in social relations binding in Somaliland. An aspect of civil cases of customary law xeer embraces, apart from civil cases, family law and the principles of hospitality belonging to the set of specific customary norms (xeer gaar) typical of the chosen lineage tol, or region gobol (here there are peculiarities of customary law in such regions as, for example, Somaliland, Saanag, Sool, Puntland, Jubaland, or even particular districts of Mogadishu, or Somali refugees camp in Dadaab, in Kenya).

The potential of xeer as a tool for resolving disputes in Somalia is appreciated by the United Nations. During field studies in 2016, the UN was interested in such issues of xeer as: dhiig – delicts; dagaal iyo nabad – the law of war customs; shaqo – labour law; dhaqan – civil law with inheritance law, but also family law. By virtue of the development programme UNDP, in 2016 it conducted in Somaliland and Somalia trainings harmonising legal values of xeer with human

rights for legal counsels of customary law (xeer beegti) and judges of customary law (guurti) familiar with the customary jurisdiction of the regions and particular clans (ugub), and their economic specialisation. While Somaliland has developed the customary law of the shepherds

– nomads, the Putland area was the seedbed for the genesis of the application of the xeer norms in agriculture, trade and maritime fisheries. Xeer of acquiring the main ingredient of the incense

– is now a ‘living law’ in this historical part of Somalia and one can assume that the rules of international trade of incense have developed as a result of the reception of habits cultivated on the ancient ‘trail of scents’ related to the principles of growing trees and extracting the resin from the Boswellia tree, of the Burseraceae family. According to the accounts from hardly accessible areas Saanag and Bari, in these regions operate customary courts xeer resolving disputes to the title of ownership to particular trees producing valuable resin. The right to inherit Boswellia tree plantations is solely reserved for the male clan members.

Fishermen and sea carriers from Berbera in Somaliland, in talks conducted in 2016, referred to the existence of customary norms on the use of the Ocean (Uruf Alba’hr) and the carriage of passengers. According to the shipowner transporting refugees from Yemen to Berbera in Somaliland, if a passenger drowns through the fault of the captain of the vessel, the customary law obliges his clan to pay diya. In the opinion of the informant from Berbera, the transport of refugees was a permanent and safe source of income in 2016 in view of the risk of piracy fought by the international community in the Gulf of Aden. The former pirates often saw themselves as the “guards of the coastline” of Somaliland, Saanag, or Puntland, pointing to the unlawfulness of foreign fishing fleets catching fish illegally in territorial waters.

Refugees in the system of Somali customary law

In April 2016, the UNHCR estimated the number of internally displaced refugees in Somaliland at about 84 thousand (which meant 23.059 families). In the very Hargeisa 45 thousand of displaced people found refuge. The UNHCR maintains that 15% of this population are internally displaced refugees from central and southern Somalia. The Somaliland authorities believe that they are foreigners subject to international protection under the UN system2. However, the High Commissioner for Refugees does not give assistance to those people by registering only refugees from Yemen, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Syria and Palestinians. According to

the UNHCR statistics, in Somaliland in April 2016, resided refugees from the following countries of origin: Yemen – 3.025 prima facie refugees and 122 applicants; Ethiopia – 2.199 recognised refugees and 7.682 applicants; Eritrea – 34 recognised refugees and 32 applicants; Syria – 132 prima facie refugees; Bangladesh – 6 refugees; Uganda – 3 refugees and 1 applicant; Democratic Republic of the Congo – 3 refugees; Congo – 2 refugees; Djibis – 4 applicants. In addition, a group of 15 Palestinian refugees lived in the country in 2016.

It can be assumed that, because of the personal nature of the customary law, the characteristic of xeer is an isolationism based on the principle that customary law is basically applied to

‘countrymen’, as in times of particularism of the tribal rights in Europe. Opening borders for refugees raises the awareness of the need to extend the patterns of finding settlements within the framework of traditional folk knowledge, also with their participation. Foreigners do not have legal capacity under xeer system and only those who are covered by the right of hospitality of the clan can be represented in a potential dispute as part of a specific guardianship of the elders. More often, this solution seems to be used by the Yemeni in the capital of Somaliland or the well-educated Palestinians. Other unqualified foreigners, mainly Ethiopians, seek asylum relying on the immunity as a result of the ‘protection’ granted by the UNHCR and aid organizations. The representatives of the Ethiopian community in Hargeisa draw attention in their talks to the issue of insecurity and frequent cases of abuse of power by the local police, whose officers know about the lack of access of forced migrants to the courts, where judges of customary law (guurti) rule:

‘They arrest me whenever they want. They do not tell me why they shut me down and when I will be released. I don’t know why they detain me’3.

Detaining and keeping in isolation by policemen is a method of threatening the leaders of the Oromia refugee community in Ethiopia. Yes, one of them reported his bad experience with the police:

‘I was beaten without any reason by the policemen from the local police station. They came after me at night and they locked me in a dark cell. Later I was beaten. They told me I was the leader of the Oromo people in Somaliland and that I have to move out home. If I do not leave, they threatened me with death’4.

Among the Ethiopian community prevails a specific intimidating atmosphere from the police, not only not responding to reports of crime, but also advising against complaining to the lawyers paid by the UNHCR:

‘The policemen threatened to take revenge if I report being beaten to the lawyers in the law clinic. Every member of our community can make a statement that what I say is true’5.

Female refugees, especially those deprived of their husbands’ protection, often fell prey to sexual violence:

‘I am alone without a man who would protect me. I have no means to rent a house and I live in the street.’6.

Lack of any protection and sanctions for a crime threatens women being in such a position of constraint with stigmatization, through which ‘they are perceived by men to be ‘available’ to all who want to satisfy their sexual urges. The victimology of these women is linked to the fact of excluding them from the protection zone of customary law and protection of the clan. As the practitioners observe, the application of the positive law, the law of Sharia and the clan law xeer – is not uniform and arbitrary. The circles of activists and advisors propose the unification of the law and the removal of contradictory norms of the positive and customary law in Somaliland and Puntland, noticing in the system of customary law the mechanism of effective and fast resolution of disputes in the poverty-stricken Somali communities.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner established in Hargeisa the Peaceful Coexistence Centre aiming to promote the values of the UN in Somaliland through educational and equality programmes. There is, however, no room for amicable settlement of disputes between refugees and their host communities. The refugees themselves critically responded to the UNHCR investment.

‘That’s a waste of money. Instead of building such centres, it would be better if UNHCR supported refugees directly. Now we are told that there is no money left for us? Has anyone asked us if we needed such a common room?’

The model of such a coexistence centre, like the one set up in Hargeisa, can be found in the host countries accepting migrants, for example in the Netherlands. The aim is to increase the tolerance towards refugees in local communities through spending leisure time together. Effective interventions of the Legal Clinic at the University of Hargeisa, which is excessively overburdened, speak strongly in favour of, in the opinion of practitioners, the need to strengthen effective measures to protect the rights of refugees, mainly by appealing to traditional and effective mechanisms of customary law xeer. The prerequisite is to gain support for the idea of integrating refugees into the xeer code from the members of clan elders, distinguishing

themselves by their knowledge and trust (xeer begti) in Somaliland. The unanimous resolution of the legal scholars (xeer begti) as regards the question of covering refugees by customary law can contribute to obtaining by them an effective legal remedy for the current position of de facto outlawed marginalised minority in Somaliland. Previously supported by the UNHCR publications positively assessed the ‘participation of tribal elders in dispute resolution mechanisms’. As one of the interlocutors noticed:

‘It will be best if elders meet with local authorities to discuss incidents”… “Elders must be present, xeer begti, government. They all should work together to resolve the dispute’8.

However, the officials of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Somaliland have not made an attempt yet to support the plan of integrating refugees into the xeer code by negotiating with clan elders. The thinking style in the collective of UN refugee officials engaged in the protection of refugees is shaping the warning against the ‘needless romanticizing’ of the customary law. The guidelines warn, first of all, against the traditionalism, which, in the opinion of the UNHCR, is a source of violence against women and children. The activity within research and application of customary law, as a stabilising factor in Somalia, showed, what I have already pointed out above, the UN Development programme for UNDP.

Justice (maslaxad) in Dadaab camp in Kenya

The practice gained in Somali refugee camps within the application of a properly processed xeer system was described in 2011 by Nikolaus Grubeck in the framework of the programme Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict (Campaign for Innocent Victims of Conflicts). In a study published on the basis of field work among refugees, there is a voice about the co- responsibility of all participants of the conflict for damage caused to civilians, including the Al- Shabaab group, but also units of the International Stabilisation Mission AMISOM:

‘People say, ‘What’s the difference between AMISOM and Al-Shabaab… AMISOM kills us. And they (Al- Shabaab) also kill us’9.

In the year 2018, the observations made during the field studies in 2016 are still valid:

‘In Somaliland and Puntland, the clan is a source of security, not UN military missions. The clan militia has – as it is defined – morale, esprit de corps and is ready to fight despite the lack of heavy armament and the high military

salary that AMISOM soldiers receive. For the local population the militia (clan) does not pose a threat which is

connected with to the presence of “Blue helmets’.

Dadaab camp, located close to the border with Somalia, is a place where the law of Kenya is over to its inhabitants. As states Ilse Griek of the Dutch Council for Refugees, an organisation

operating under the international refugee regime, as a partner of the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees, … ‘the lack of documents, as well as the low number of crimes

reported to different NGOs, the UNHCR or the police (especially sex crimes), do not allow to assess the dark number of violations of law and how many cases have been judged under the

customary law of refugees.’

In Dadaab camp, the xeer system is defined by refugees by the word ‘justice’ – maslaxad. To

the maslaxad system refer all the remarks listed above. In the refugee camp, officially under the aegis of the UNHCR, the rape victim can be forced by the tribal elders to marry a rapist and pay compensation (mag-diye) to her father or the oldest man in the lineage for the act of

‘disgracing the honour of the clan’. This is in line with the tradition of customary norms, regardless of the UN-led trainings on ‘peaceful coexistence’ in the common rooms located in the separated from the rest of the camp security enclaves, where reside and work female and male activists of the international refugee regime protected by armed guards.

The inhabitants of the Horn of Africa, as well as refugees from Dadaab camp in Kenya, depend on transnational financial assistance from the clan members who have been granted the right of residence in the host countries. In connection with sanctions preventing the use of bank transfers, money transfers are made under customary law. A money order between the United States, Norway, Australia and the recipient in the Dadaab camp is made on the basis of an oral transfer xawilaad, without the involvement of online banking or accounting records, relying on trust in the participants of the transaction. In the camp, intermediaries use their own radio network and secret cash points. Research on the functioning of the customary system of money transfers xawilaad surprised with the results revealing the size and the amount of concluded transactions. Other findings of the field research included the confirmation of the reliability of such a flow of funds, initiated and carried out beyond any control of the state service.

A cashless transfer xawilaad within the xeer system constitutes the basis for the socio- economic life of the Dadaab camp. Customary banking law is a key factor in the process of building bonds between humanitarian nomads in Somalia and transnational nomads across the

ocean or in European countries. According to national security experts, this institution of

customary law is unfortunately also widely used by transnational networks of world terrorism

to finance their organised criminal activity.

Lack of actual state control over Somali refugees and their introduction of Somali orders not

subject to the influence of foreign countries poses a problem for the security apparatus. In May

2016, Joseph Nkaisserry, a high-level official of the Kenyan authorities negatively assessed the

state of affairs on the example of Dadaab camp:’…Camps have become a place of refuge for Al Shabaab and also centres of smuggling, leading to the proliferation

of weapons in the region. Considering the scope of global terrorism, with its new manifestations trying to implant in our region, it would be unforgivable for the government to shift away from its superior constitutional duty to protect its citizens and their property’.

A loud decision taken by the Kenyan authorities to close the Dadaab camps triggered protests of humanitarian organizations. In the years 2014 – 2018 on a voluntary basis, backed by UNHCR, 76.589 refugees returned from Kenya to Somalia. According to the information received from UNHCR officials in July 2016, in the Dadaab camp resided 327.320 Somali refugees for whom customary law was the main instrument to maintain the traditional social order in camp conditions.

Final remarks

The customary law xeer constitutes an evidence for the effectiveness of traditional folk knowledge as an effective, anthropologically rooted, dispute resolution tool. The principle of personality of the customary law fares well in solving clan disputes in Somaliland. The search for law and justice in disputes involving foreigners seeking protection there is possible under official, positive law, which is not guaranteed by virtue of a settlement between the lineages. Countries, de facto, such as Somaliland, do not have at their disposal enough force of constraint to enforce judgments of common courts. Refugees, as ‘the charges of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’, have a low sense of security from the international refugee regime. UNHCR is reluctant to the proposal of reducing its discretionary power over refugees and evades attempts to get to know the mechanisms of customary law, not to mention its implementation. The protection of refugees through customary law can be easily criticised as an activity not clinging to the standards of the XXI century, and what is worst of all, can also be stigmatized by donors who are humanitarian assistance operators. Adopting an alternative order of interactions between the institutions of the international refugee regime with the

‘charges’ – would mean a loss of power and strong supervision.

The UNHCR’s aid programmes can also be perceived as part of the ‘rituals of transition’ from the perspective of Arnold van Gannep. The transition through the liminal phase at the exclusion stage in refugee camps is supposed to ‘liberate’ international humanitarian organizations from the inhibiting and irritating traditionalism. The agency of UNHCR’s charges in the process of adaptation to life in the refugee camp is based on their commitment to interaction with ‘the use of knowledge, innovation and practices’ from their cultural heritage. The forced migration of Somalis from the southern part of Horn of Africa to Kenya did not lead to the helplessness and vulnerability of refugees thanks to the vitality of traditional folk knowledge in the conditions of exile in Dadaab camps in Kenya. Within 25 years of the Dadaab camp operation, a variation of customary law has developed there. Maslaxad has become the basis of the socio-economic life of the community of more than three hundred thousand of Somali refugees living there. Despite the ongoing programmes financed by the international refugee regime in refugee conditions, the model, in which the traditional elder’s clan structure was removed from the impact on the young generation, has not been rejected.

Modern education, as a prerequisite for the increase of a social status and departure from the closed camp community does not lead to cultural eradication. Refugees, who have managed to continue migration, also use the traditional system of money transfers xawilaad to support other clan members who stayed in the Horn of Africa. Similar traditionalist identity attitudes motivate the already educated at the Western universities former male and female refugees to return to Somaliland. They decide to repatriate to support development projects in this part of Somalia, where now prevails peace. The study of the Somali diaspora shows that staying abroad is by no means leading among Somali migrants to the erosion of clan ties and respect for their own traditional folk knowledge, including the customary law xeer. The Somali community in the diaspora maintains strong transnational ties with the country of origin, which contributes to the political and socio-cultural transformation of Somalia, based, however, still on traditional knowledge and enriched by the social capital of the diaspora, as it happened before in Somaliland.