Hargeisa Invisible City Somaliland

Invisible City: Hargeisa, Somaliland

David Kilcullen

Introduction

When Afrah and her family left Hargeisa in 1988 she was just seven years old; like many townspeople who fled that year, she remembers a very different city.1 Former seat of government of Britain’s colonial Somaliland Protectorate and (for five days in June 1960) capital of the independent State of Somaliland, by the late 1980s Hargeisa—then a northern provincial city under socialist dictator Siyaad Barre’s epically dysfunctional Somali Republic—was rapidly collapsing. At least 80% of the town’s buildings had been reduced to rubble, and more than 50,000 members of the region’s majority Isaaq clan had been massacred by government death squads in what observers later dubbed the “Isaaq genocide.”2 Even today, unmarked graves of dozens killed in the 1980s are still being discovered near Hargeisa.3 By late 1988 most of the city’s population of 500,000 had been put to flight by bombs dropped from MiG-17 jets of their own Somali Air Force. Eyewitnesses told of warplanes launching from Hargeisa Airport on the city’s southern outskirts, turning back to bomb the town from which they’d just taken off, then landing at the same airport to rearm and repeat.5 It was one of Barre’s last acts of large-scale violence and repression before his brutal regime collapsed and he too was swept away. A regime MiG shot down in the fighting by local guerrillas of the Somali National Movement (SNM) now serves as a war memorial, perched on a plinth in downtown Hargeisa’s appropriately-named Freedom Square.

Looking out the aircraft window as you land today at Hargeisa Airport, with its modernized terminal and newly-extended runway, you see an almost completely rebuilt city. Driving into town you pass welcome signs from the Republic of Somaliland, official buildings bearing the government’s banner, neatly-uniformed unarmed traffic police directing a bustling flow of vehicles, and a series of thriving shops, hotels, cafes and restaurants. Hargeisa’s population today is 1.2 million, roughly a quarter of the total population of Somaliland.6 The city has a safe, open, friendly vibe, even after dark—almost unbelievably so for anyone who has spent time in Mogadishu, or even other East African cities such as Mombasa, Maputo or Dar es Salaam. Many buildings are under construction; market stalls stocked with fresh fruit and vegetables (mostly imported from Ethiopia) and manufactured goods (from Vietnam and China) line the roads. To be sure, those roads are absolutely terrible, sheep and goats graze the city streets, and a fine grey dust covers almost every surface. At 2:30 each afternoon—peak period for khat, Khat since trucks distributing the drug arrive from Ethiopia around 2pm, through checkpoints where officials collect excise—vehicles strop randomly in the street while satisfied customers wander with leafy-topped bunches of the tightly-wrapped twigs. But modern malls and supermarkets are also springing up; billboards advertise banks, boarding schools and universities, and the MiG monument—which, in photographs as recent as 2012 appears to sit in an empty square—is surrounded by stalls and overshadowed by bank buildings and telecoms offices. Given all that, you could be forgiven for thinking you’d arrived in the thriving capital of a rapidly developing, well-governed, independent sovereign country, a town focused on commerce and construction, and determined—thirty years after its destruction by Barre—to put the past behind it. But you’d be wrong, for Hargeisa is an invisible city.

Invisible City

The sovereign Republic of Somaliland appears on no maps. It is listed in no official register of the world’s countries, has no seat at the UN and no international country code. Government officials are forced to use personal email addresses because there is no national internet domain, and the country is unrecognised by the international postal union, so the only way to mail something from Hargeisa is via the slow and expensive DHL shipping service.8 Instead, the country is described as the “self-declared but internationally unrecognized republic of Somaliland” and considered by the international community to be a breakaway region of the Federal Republic of Somalia—the successor to Barre’s regime,inaugurated in 2012 after decades of lethal anarchy in the south, cobbled together by the international community with United Nations supervision and under the guns of an African Union peacekeeping force. Everything in Hargeisa—from the peace treaty pulled together by visionary elders in 1991, to the city’s self-financed rebuilding, to the unrecognised state of which it forms a part, to the largely informal economy and homegrown political system that sustains it, is a bottom-up, do-it-yourself enterprise. This enterprise, evolving over the past 28 years through a remarkable process of self-help, emerged not only without much international assistance but, at times, against active opposition from the world’s self-appointed nation-builders and doers of good.

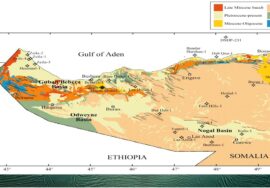

While the world was watching Somalia shred itself in a clan bloodbath and apocalyptic famine in 1991-93 (the setting for the book and movie Black Hawk Down, the defining image of Somalia for many westerners) an extraordinary process of grass-roots peacebuilding was quietly taking place in the north. Over many months in 1991-93, Somalilanders met in the Berbera, Sheikh, Guraay and Boorama peace conferences, a series of local reconciliation meetings brokered by traditional elders, resulting in peace agreements which then proliferated throughout the former territory of British Somaliland, and its mostly Isaaq and Darod clan groups.9 A constitutional convention, and subsequent regional reconciliation agreements formalized the establishment of an executive presidency accountable to a bicameral legislature, with a lower House of Representatives elected by the people, and an upper House of Elders elected by clans. A constitutional convention later confirmed this setup. Somaliland’s governance structure—which has been described as a “hybrid political order”— may sound exotic, but the House of Elders has essentially the same function as the British House of Lords, or the Senate in Australia or the United States.10 It plays a key role maintaining balance among the clans and geographic regions that form an essential element of Somaliland (and indeed greater Somali)11 life. This serves to contain the destabilizing, often lethal, escalation of zero-sum competition among clan factions that has occurred elsewhere. This practical experiment in state-building has proven remarkably robust: Somaliland today possesses an independent judiciary and a free press, and peaceful transfer of power between Presidents following free and fair elections has become the norm. It is also enduring, with 28 years of homegrown stability and internal peace offering a stark contrast to the internationally-enabled chaos and violence in south-central Somalia. As capital of a country that officially doesn’t exist, Hargeisa has no formal status. Yet, as a practical reality, it’s a thriving commercial hub, the seat of a government that considers itself sovereign, is regarded as legitimate by its population, and administers one of the more stable, peaceful and democratic states in Africa. Hargeisa has consulates from Turkey, Ethiopia and Denmark, receives international flights from Dubai and Addis Ababa, and hosts UN agencies, international aid missions and Chinese, Kuwaiti and Emirati businesses. Invisible they may be, but Hargeisa—and Somaliland—are very real. But there’s another, even more important, sense in which Hargeisa is an invisible city. If we think of it as simply a piece of urbanized terrain, “Hargeisa” is a town of roughly 1.2 million people in the north-western Horn of Africa, its streets laid out in a grid pattern over about 33 square kilometres, situated on a cool plateau 4400 feet above sea level, in a rough hourglass shape (see Figure 1) astride the usually dry Maroodi Jeex (“Elephant Creek”) and connected by road to the port of Berbera, two hours’ drive away on the Gulf of Aden. But the real city is vastly more than that. If, instead, we consider Hargeisa as a system, with the city’s relatively small area of urbanized terrain sitting at the centre of a vast social, political and economic ecosystem that includes not just the town itself but also its diaspora—the thousands of Hargeisans who live in Europe, America, Ethiopia, Kenya, Canada, Australia, the Gulf states and elsewhere, connected to their city through remittances, e-banking, mobile telephones, Skype, social media, family ties, business deals, visits and investments—then we have a much clearer idea of what the city is and how its political economy works. Take Afrah, for example. Growing up in the United Arab Emirates and United States, she is well-educated, with degrees in hospitality and tourism, an experienced manager and businesswoman who moved back to Hargeisa several years ago to look after her elderly mother, and ended up launching a business with savings cobbled together during her time overseas. Today her tea room employs 25 people and does a lively trade serving civil servants from nearby ministries; she has reluctantly turned down offers to franchise her brand in other parts of the region. Like many business owners (and, seemingly, most of the officials who patronise her café) she holds two passports, has relatives in several countries, speaks multiple languages, and travels regularly to Dubai for banking and to supervise shipments for her business or meet investors. Far from being a theoretical construct, the Hargeisan diaspora is an ever-present social, political and economic reality. Somalilanders in the diaspora account for more than USD $700 million in annual remittances—and much of that money flows to or through Hargeisa.12 (For comparison, the total national government budget of Somaliland for 2018 was $382 million, just over half the value of remittances.)13 In effect, the human and communication networks and financial flows centred on the city, invisible though they may be, are its lifeblood, even though many nodes in these networks are not physically in Hargeisa at all. On a map of this real but invisible Hargeisa (see Figure 2) significant parts of the city, much of its population—and most of its wealth—are in Amsterdam, Cape Town, Copenhagen, Dubai, Durban, Düsseldorf, Helsinki, London, Minneapolis, Nairobi, Oslo, Portland, Seattle, Sydney and Toronto. Understanding Hargeisa-in-Africa (Hargeysa ee-Afrika) in this way, as the tip of an iceberg, or one tree in a grove of trees with a single root system, is the key to seeing the real, invisible, Hargeisa-the-city (Hargeysa magaalada).

Clan and Camel

While Hargeisa’s global connectivity is a new phenomenon, emerging around the year 2000 due to increasing ease of air travel and money transfer, proliferation of smartphones, penetration of the internet and thus closer ties to the diaspora, it is utterly traditional for Somali city-dwellers to maintain social and economic links to a rural hinterland, and to the pastoralist nomads who tend flocks and herds in the interior. Of Somaliland’s population of

4.5 million (an estimate only, since the most recent census, conducted by the Barre regime back in 1981, almost certainly under-counted the country’s northern population) about 55% are nomadic or semi-nomadic, while 45% are urban. Pastoral nomadism—the tending of seasonally-roaming herds of camels by men and boys

who follow the rainfall (and therefore pasture) patterns, or of sheep and goats in static camps by women and girls—is the traditional, and in many ways the defining feature of Somali life and culture. Droughts in 2011-12 and in 2017 severely depleted livestock, particularly camel herds, in the interior and drove many pastoralists off the land and into slums on the city’s edges, while rains in 2018 (though better than in recent years) have not yet enabled a rebound. Yet Somaliland’s only significant export remains the live animal trade to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, while the four noble clans of the ethnic Somali region (including the majority Isaaq clan of Somaliland) are all pastoralists. Fishing villages, farming communities and urban artisan and merchant centres do exist, but these sedentary

populations were traditionally the object of pastoralist contempt, and of periodic plundering by desert raiders. Somalilanders’ way of life is still, even in 2018, closely tied to the herd and,

above all, to the prestige and power of camel and clan. Not that the city is separate from the clan: quite the contrary. As the great scholar of Somalia and Somaliland, Ioan Lewis, has written, “nomads are not cut off from the life of urban centres or culturally and socially separated from the majority of urban residents…from the President downwards, at all levels of government and administration, those living with a modern lifestyle in urban conditions have brothers and cousins living as nomads in the interior and regularly have shares in joint livestock herds. Civil servants commonly invest in livestock, including camels, that are herded by their nomadic kinsmen.”

The Meccan hajj is the peak period for the trade in sheep and goats—demand in Arabia spikes during and before the holy month of Ramadan, when demand for food spikes in Saudi Arabia and millions sacrifice animals as part of the traditional pilgrimage. Supply of camels for milk, meat and transport is also a key export to the Gulf states—and a much higher prestige occupation than the trade in small stock. The camel trade, too, is currently depressed; in part this is due to the ongoing war in Yemen, Somaliland’s nearest Arab neighbour, lying only 260 kilometres away across the Gulf of Aden, which has massively disrupted export networks. Outbreaks of Rift Valley Fever in recent years also resulted in bans (now lifted) on exports to Saudi, Emirati and other regional markets.

Even on a quiet day, and in the trade’s currently-reduced circumstances, Hargeisa’s livestock market (at Seylada, in the band of open ground running through the city just south of the river) is a place of bustling activity. Herders display stock for evaluation by canny brokers

who then make personalized deals with hard-bargaining individual export merchants. Herders, brokers and merchants alike mostly wear traditional dress and are often older, since many of Somaliland’s young people have abandoned the austere herding lifestyle over the past generation for jobs (or non-jobs) in and around Hargeisa. Appearances are deceiving though, yet again: despite leathery faces, traditional walking

sticks and travel-stained garments, each herder carries at least one mobile phone, and is intimately familiar with the current international market rate for each type and grade of animal, changing minute by minute and continuously updated via text message. He negotiates with brokers while simultaneously checking in—on WhatsApp or other social media—with his extended kin, whether sitting in makeshift tents in the interior, air conditioned offices in downtown Hargeisa, or internet cafés in Rotterdam, Oslo or Minneapolis. This family network—part-owners and co-investors in the livestock being traded—must be satisfied before he can seal the deal. Again, traders haggling over Somali tea in the shade of a row of eucalypts along the edge of the market may appear, to the casual observer, like throw-backs to a simpler age, but these are really international businessmen navigating complex multi-party deals, in a global market, with a floating exchange rate, under the close scrutiny of a stakeholder network that exists in the invisible, global Hargeisa—not just the physical one. This means that cities like Hargeisa are not now (nor in fact have they ever been) islands of settlement in a sea of nomads—like some towns in Yemen, Oman or Central Asia. Rather, Somali cities are closely tied to their hinterlands and to the diurnal and seasonal flows of wealth, commerce and labour that eddy around and through them. In Somaliland in particular, even more than in other parts of the Horn of Africa, a long-standing tradition of individual labour migration also exists, with locals working abroad as seafarers, labourers or traders across the region and further afield.18 When the city emptied under Barre’s bombs in 1988, people fleeing Hargeisa therefore were able to plug into a pre-existing web of external connections and support networks—the starting point for a process of chain migration that helped create today’s massive diaspora.

Diaspora and Development

One effect of this diaspora today is that Somalis are now the world’s largest per capita recipients of remittances. Traditionally, livestock exports accounted for most of Somaliland’s inward cash flow—and as we’ve seen, the live animal trade still represents the country’s largest source of export dollars, though the government is urgently seeking to diversify the economy in the face of drought and regional instability. Nevertheless, in terms of raw financial flows, as of 2018 more than 60% of the country’s income derives from the diaspora. Between 25% and 40% of Somaliland households receive remittances from relatives overseas; total annual remittance inflows in 2013-14 totalled USD $780 million, of which 70% went to individuals and families and 30% to capital or financial investments.20 This makes remittances the single biggest inflow to Somaliland: bigger than aid, humanitarian assistance and trade combined and, as noted earlier, roughly twice the size of the entire national budget. Remittances mostly go to servicing household costs and recurrent expenses; some contribute to diaspora-owned businesses which create jobs in Hargeisa and other towns. Remittance transfers are made using traditional hawala networks, via Islamic banks such as Dahabshiil (the dominant player in Hargeisa’s financial sector) and distributed platforms like WorldRemit which use smartphone technology and are increasingly preferred for security and speed.21 In a city that lacks a modern conventional (i.e. non-Islamic) banking system, within a country that is unrecognised and therefore only tenuously connected to global banks, mobile money transfer is a common payment method for everything from food and fuel to payroll and business purchases. Popular platforms include e-Dahab (affiliated with Dahabshiil but administered as a separate business and partnered with Somtel) and ZAAD, pioneered in 2009 by Somaliland’s Telesom mobile phone company. ZAAD is a direct system in which merchants (rather than agents, as for systems such as m-Pesa) form the principal access point for customers and users. A user may purchase Telesom airtime with cash from a merchant, add cash as needed to finance purchases, store money, and receive or transfer funds internationally through ZAAD’s connection with WorldRemit. As Claire Pénicaud and Fionán McGrath noted in a July 2013 case study, since its creation in 2009 ZAAD has gained significant traction: “in June 2012, almost 40% of Telesom [mobile phone] subscribers were active users of Telesom ZAAD. What is most striking about the service is the level of activity on the mobile money platform. Active Telesom ZAAD users perform over 30 transactions per month on average, far above the global average of 8.5 per month. The World Bank’s Global Financial Inclusion Database (Findex) recently revealed that Somalia was one of the most active mobile money markets: 26% of the population reported using mobiles to pay bills, which is the highest rate in the world, and 32% to send and receive money. Most of this mobile money activity has been driven by Telesom ZAAD.”22 As Pénicaud and McGrath note, Telesom learned from the experience of pioneers like m-Pesa in Kenya to focus on building a peer-to-peer payment ecosystem, which has succeeded in encouraging Commented [OJD7]: Dahabshiil also owns Somtel users to store money for payroll and business transactions, not solely for short-term transfer. Five years on, ZAAD is increasingly being challenged by competition from e-Dahab (partnered with Telesom’s competitor Somtel). One problem with this system is another artefact of the reality that Somaliland is unrecognised, namely that mobile phone users cannot call phones on other networks—Somtel users, for example, cannot reach the mobile of someone on the Telesom network, since the two networks have incompatible numbering systems and work on the Somali (as distinct from Somaliland) country code. As a consequence, many Somalilanders carry two mobile phones, or go through the awkward process of continually swapping SIM cards between phones in order to communicate.

Futher, counterintuitively, the use of electronic money underscores just how cash-based (as distinct from credit-driven) Hargeisa’s economy is. Islamic banks like Dahabshiil do not offer credit cards, though they do furnish fee-paying debit and ATM cards, and their deposit accounts do not carry interest. So, most people work in cash, withdrawing notes from ATMs then either paying cash or loading value into ZAAD or e-Dahab accounts on their phones by buying airtime from merchants. Somaliland maintains its own currency—the Somaliland

Shilling (SlSh)—as yet another indicator of its real though unrecognised sovereign status, and small purchases are often made in SlSh. But to a surprising extent the country’s real economy is based on the United States dollar. In part this is because Somaliland’s unrecognised status makes it hard to conduct in SlSh the international transactions that form the bulk of the country’s financial flows; in part consumer confidence in USD reflects recent instability and inflationary pressure on the Shilling. The Somaliland shilling, indeed, has been historically unstable and not widely trusted; there were currency crashes in 1994 when the government introduced the Shilling to finance a conflict against rebellious clans in the eastern region, and again in 2002-3 when the government printed huge amounts of money to finance a constitutional referendum and parliamentary elections; then the Rift Valley Fever crisis when Gulf countries banned livestock imports from Somaliland created further currency pressure. Either way, though ATMs have proliferated in the past few years, and it is technically feasible to use international credit cards for an increasing range of transactions, hard currency—overwhelmingly, American dollars—is the basis for commerce in the city. Although money transfers and remittances may seem like a success story—and indeed, they do represent remarkable innovation in inclusive banking—like the reliance on US dollars, they highlight a key structural issue in Hargeisa’s economy. Because Somaliland imports virtually all products, from food and fuel to cars and clothing alike, remittances operate much like foreign assistance in a war zone: like so-called “aeroplane aid” in Afghanistan, remittances come into Hargeisa, touch down briefly, then fly right out of the country again as they are used to purchase goods that are overwhelmingly imported. Only a small proportion of financial remittances—that percentage used to create jobs or finance businesses—remains in Somaliland to help build economic capacity. Moreover, since the government levies no tax on remittances, this largest financial inflow (and the largest single source of private income for Somalilanders) generates no income for the public. But financial remittances are not the only inflow from the diaspora. In addition, intellectual remittances—technology, skills and knowledge transfer to Somaliland from people who have lived and been educated overseas—help build Hargeisa’s human capital. Returnees from the diaspora are over-represented within elites in Hargeisa, including civil servants, political and business leaders, heads of community organizations and entrepreneurs. This can help build capacity, as the “brain gain” from returnees—visiting or moving back to Hargeisa, helping establish businesses, schools and clinics, or representing the country’s interests overseas—contributes to Somaliland’s development. For many families, sending a child overseas for work—or more recently, committing family members to the dangerous gamble of emigration to the Middle East or Europe—is a strategic calculation aimed at diversifying the family’s income or improving its human capital. Still, from a social and political standpoint, the return of Somalilanders from the diaspora is not always uncontroversial. Hargeisans who have spent the past three decades dealing with the fallout from war and state collapse can sometimes cast a sceptical eye on returnees who have lived relatively comfortable lives overseas, the more so since their presence drives up housing, commodity and real estate prices (already extremely high, by local standards, in Hargeisa) while their deeper pockets and access to overseas cash exert upward pressure on essential consumer goods.There are subtle but significant linguistic differences between returnees and locals, which (along with the returnees’ dress and standard of living) sets them apart, and some— particularly those seeking senior political or civil service roles while holding dual nationality—can even be seen as opportunistic carpetbaggers. This, of course, is a common problem in cities experiencing a post-conflict return of refugees, and that return is in itself a good thing, as it contributes to the city’s human and financial capacity and helps unlock opportunities for growth that benefit everyone, not just the returnees. But managing it is neither simple nor risk-free.

A two-speed city

Driving or walking around Hargeisa, one is struck by the contrast between a private economy that is clearly thriving, and a lagging public sector—including, particularly, urban infrastructure. While not a true reflection of John Kenneth Galbraith’s “private affluence and public squalor”—since even the private sector is far from opulent in Hargeisa—this is plainly a two-speed city.27 The reasons for this are not simple (and neither is dealing with their consequences) but one clear cause is the lack of a broad tax base. The government does not tax income, nor does it levy duties on remittances. It collects excise on khat imports, and duties on other goods coming in through ports and airports, as well as landing fees and other payments from users of those points of entry. Businesses are taxed at 12%, as are payrolls at 6% and sales at 5%, but these rates sustain only a very austere and limited government structure, one that lacks the resources to invest in public goods that could jump-start private development. Somaliland’s six regions and 23 city governments raise taxes from their own localities and then plough this back (with varying degrees of probity and competence) into development at the city level, and cities like Hargeisa and Berbera that operate international points of entry are allowed to keep a portion of their earnings. The lack of income tax is understandable in a country whose economy is largely informal or subsistence-based. But the failure to tax remittances (or offer Somalilanders in the diaspora opportunities to contribute to a public investment fund) is one clear area for consideration. Roads are an obvious example where the lack of resources for public investment hampers Hargeisa’s economic activity and social development. The city’s central avenue (running through the downtown area, past the Presidential palace and government ministries) is the only decent tarmac road in the city. Virtually every other paved street is potholed, and outside the business district many roads are gravel or dirt. There are few gutters and no properly-constructed drainage system, so that on the rare occasions when significant rain falls, large areas of the city are flooded and roads are impassable due to mud. The resulting wear-and-tear on cars and trucks (mostly Toyotas and Hondas imported second-hand by ship from ports in the Arabian Gulf) imposes drag on business and household economies, while the time and cost of moving goods and people about the city is

multiplied manyfold. Well-constructed houses and businesses (built, almost without exception, since the 1990s) sit on pitted and poorly drained roads, in a physical reminder of the mismatch between a thriving private sector and a bare-bones public purse. But the city’s two-speed nature emerges most obviously in terms of basic household necessities such as water, electricity and fuel, where government investment in essential services lags private enterprise which provides—for those who can pay—a relatively high standard of service. Fewer than one in 100 households in Hargeisa has access to running water, with access dropping off sharply as one moves out from the city centre. Most middleclass households purchase plastic or metal water tanks which they place on the roadside and replenish by purchasing water from donkey-driven carts that roam the streets at most hours of the day. One thousand litres of water costs roughly USD$6 as of late 2018, and lasts a family of four about 10 days.29 The carts are regulated by government, but the water they carry comes from private reservoirs and wells many miles from the city, and is hauled by commercial tanker trucks to water distribution points where donkey carts (also privately owned) purchase the water and sell it on to consumers. In poorer areas—such as the informal settlements peopled by new (or not-so-new) arrivals from the countryside—women and children gather around plastic water drums dropped by trucks every few days, and haul the water away in jerrycans for household use. A private consortium, part of a project underway since mid-2018 with funding from the

German aid agency and limited public funds, is installing a water distribution pipeline and a system of household water supply, as well as public taps. The project, expected to take three to five years, will go a long way toward ameliorating this situation.31 Still, given how arid Somaliland is, and the known correlation between water insecurity and urban unrest, the precarious water situation for ordinary Hargeisans—most particularly, those in informal settlements who are already the city’s most vulnerable—is one of the major risks facing Hargeisa, and a key obstacle to growth and stability. Likewise, extended periods of future drought (and the inevitable depletion of artesian and surface water over time) pose a national-level risk to the stability of Somaliland and the entire region, and the amount of time and effort ordinary Hargeisans are forced to put into basic tasks like hauling water represents a severe productivity burden on the economy.

Electricity and fuel supply in turn are closely linked, since virtually all electricity generated in Hargeisa comes from diesel-fueled generators running on imported petroleum. Some are large-scale, corporately-owned generators from which businesses and households purchase

their electricity via a private metering system; others are household generators run by petrol or diesel purchasing from service stations across town. These stations in turn are serviced by fuel tanker trucks running overland from Ethiopia or up the road from Berbera, which has an oil storage terminal. Somaliland, of course, has ample sunlight with more than 340 sunny days per year, and the Hargeisa region has also been assessed as one of the most promising locations for wind energy in Africa; small-scale solar installations are common and a pilot wind energy project exists on the city’s outskirts.32 But for now, most Hargeisans depend on imported fuel, creating vulnerabilities at city and national level, and hampering commercial development through lack of lighting, assured cold-chain storage, and air conditioning.

Fuel for cooking presents a similar pattern. More than 80 per cent of people in Hargeisa cook with charcoal, produced by local charcoal-burners who cut down and burn off the tree cover—mostly acacia thorn-scrub—from areas 20 to 100 kilometers from the city. Bags of charcoal are then collected by companies who purchase them from local producers, transport them to Hargeisa, and sell them to shop owners and small merchants. People purchase bags of charcoal with their groceries from markets. At the upper end of the socio-economic scale, another 10% of Hargeisans cook with small propane bottles purchased through container-exchange schemes from local shops, or from companies like Somgas, while a further 10% or less have access to large propane tanks filled directly from tanker trucks. Again, major supply-chain assurance risks (and associated costs) result from this dependence on commodities imported from the countryside, in the case of charcoal, or from overseas in the case of natural gas.

The charcoal trade carries additional vulnerabilities, since it has been banned by the United Nations because the al-Qaeda affiliated Somali guerrilla group al-Shabaab makes so much money from it. There is little evidence of Shabaab in Somaliland at present—the group is largely restricted to south-central Somalia, and in any case many Shabaab belong to the Hawiye clan which has no significant presence in Somaliland. Still, Shabaab have started rebranding Somali charcoal as coming from somewhere else in order to sidestep the UN

embargo, and this may have disruptive effects in Somaliland and elsewhere. Likewise, for an arid country with unreliable rainfall and sparse tree cover at best, continuing to burn trees for fuel is not necessarily a sustainable long-term approach. The case for international recognition The risk that Shabaab activity in Somalia may have flow-on effects for Somaliland is just one of many ways in which Somalia’s continued claim over Somaliland (and the associated lack of international recognition) hurts the country. Hargeisa gets fewer than 2000 tourists a year, even though it is a remarkably safe and friendly city, precisely because many potential visitors (and, more importantly, their travel agents and insurance companies) fail to understand the difference between Somaliland and its violently unstable southern neighbour. Likewise, an arms embargo maintained by the United Nations keeps Somaliland’s coast guard and police without the advanced equipment needed to guarantee coastal and urban public safety. The lack of international recognition contributes to a dearth of foreign direct investment which, along with limited access to international banking, hampers Somaliland’s access to regional and global trade, and slows the exploitation of mineral deposits and oil and gas reserves that could help free the country from its reliance on livestock exports and its dependence on imported commodities. The ability to issue sovereign debt or access international loans (which also requires recognition) would also make a huge difference in the largely-underfunded public service and infrastructure sectors. Somaliland’s substantive case for recognition is, indeed, extraordinarily strong. On the one hand, the country clearly meets the definition for statehood laid out in the 1933 Montevideo Convention—it has a defined territory, a fixed population, a government in effective control of its territory which administers (and is seen as legitimate by) the population, and is capable of entering into relations with other states.33 At the same time, a peaceful transfer of power between legitimately elected heads of government has occurred several times in Somaliland’s almost 30-year history, while its relative lack of corruption, free press and independent judiciary give Somaliland a better track record of responsible government than almost any other state in Africa.

Somaliland—as successor state to the British Somaliland Protectorate, existing wholly within the boundaries established by colonial powers and with no territorial claims on any other state, also fully meets the terms of the African Union (then Organisation of African Unity) 1964 Cairo Declaration in which the union undertook to respect the former colonial borders in Africa as a means of minimising border disputes.34 Indeed, due to its real (albeit brief) existence as an independent state in mid-1960, during which Somaliland’s independent sovereignty was recognised by 35 countries, it’s at least arguable that Somalland’s declaration of statehood on 18th May 1991 should be seen as a resumption of pre-existing sovereignty, triggered when the Republic of Somalia collapsed, rather than a unilateral declaration of independence.35 Likewise, the often-applied designation of Somaliland as a “breakaway region” of Somalia, a state that had ceased to exist when Somaliland resumed its prior independence, is a legal fiction, since no functioning state existed for the country to break away from. The brevity of Somaliland’s independence in 1960 has no bearing on the legitimacy of its claim, of course, especially since it was recognised at the time by so many countries. But even if it did, Somaliland has been a sovereign, independent state almost as long as it was part of Somalia, even as that country lurches from one barely functioning government to another. This is not in any sense to criticize Somalia: that country has suffered immensely from a series of ill-judged and poorly-supported international interventions since 1991, experiencing clan-driven violence and famine in the early 1990s, neglect and chaos for much of the next decade, and then destabilisation as a result of the War on Terrorism after 2001. A series of foreign military interventions since 2006 arguably triggered the rise of alShabaab, and the ongoing instability and violence in the south is as much the international community’s fault as that of Somalis. But given the history—both in the colonial period and during Siyaad Barre’s misrule—the most stable and sustainable relationship between Somalia and Somaliland is likely to be that of friendly but independent neighbours. Those who suggest that ethnic identity—Barre’s “greater Somalia” dream—should encourage Somalis and Somalilanders to join a greater federal state, should consider that the Republic of Somalia has equally strong ethnic ties to Djibouti, the Northern Frontier District of Kenya, and the Ogaden region of Ethiopia. Leaders, since Barre, across the Horn of Africa (including in Somalia) have wisely refrained from resurrecting his deeply destabilizing irredentist campaign for ethnic unification. These merit-based arguments aside, there is a practical reason why Somaliland should be strongly considered for international recognition, namely the country’s ongoing contribution to regional peace and stability. As well as receiving and caring for large numbers of refugees from Syria and Yemen, and occasionally from drought-stricken areas of Ethiopia, Somaliland provides a valuable service to the international community by securing its 950-kilometre coastline in the Gulf of Aden, providing security for international shipping in one of the world’s major sea lanes, ensuring safety of life at sea, and generally being a good (albeit unrecognised) international citizen in a dangerous neighbourhood. The Somaliland coast guard, with its headquarters in Berbera and bases along the coastline, could perform this role more effectively if Somaliland were recognised and brought into a regional security

architecture, if the UN-imposed embargo were lifted, and international funding and assistance were brought to bear on Somaliland’s law-enforcement and regional security assets. There are, of course, some reasons to be cautious about international recognition. As noted, the international community’s attempts to assist Somalia have been far from helpful, and the paradox of Somaliland is precisely that it has been so successful with an unaided bottom-up strategy of self-development, so that it might seem to be tempting fate to invite the international community in at this late stage. Likewise, from a geopolitical standpoint, Western powers may prefer Somaliland to remain unrecognised since, in their competition for presence and influence with China, Somaliland’s unrecognised status has been a key deterrent to Chinese engagement in Somaliland (unlike most of the rest of Africa) since recognising Somaliland might open up calls, unacceptable to Beijing, for recognition of Taiwan, Tibet and Xinjiang. Yet these are not arguments for continued non-recognition: rather, they represent reasons for a measured approach, with strong engagement with Somalilanders (both in Somaliland and in the diaspora) and the government in Hargeisa in charge of the process. Given Somaliland’s track record of good governance, and the maturity of its institutions after 30 years and several peaceful and stable changes of government, this would seem eminently doable.

Ports and bases

This discussion of international recognition may seem off-topic for a city-level analysis of Hargeisa. In fact it is central to the city’s future, since (besides being the capital and by far the largest city in Somaliland) Hargeisa forms a key node in the largest, and most potentially transformative infrastructure project in Somaliland’s history. This is the major upgrade of the port of Berbera and the associated construction of a Berbera-Hargeisa highway corridor, which could open Hargeisa as a hub for a regional transport and trading network that would transform the city while opening major economic development opportunities for the region’s major power, Ethiopia. Dubai Ports World signed a USD$442 million agreement with Somaliland in 2017, forming a joint venture (DP World Berbera) with the government of Somaliland, while Ethiopia tool a 19% stake as a shareholder. The company was awarded a 30-year concession, with an automatic 10-year extension, on the port of Berbera, in return for a commitment to double its size and transform it from a manual stevedoring operation into a modern container terminal.36 Work commenced in October 2018, and involves “building a 400-metre quay and 250,000 square metre yard extension as well as the development of a free zone to create a new regional trading hub”.37 The deal included a commitment to upgrade the road between Berbera and Hargeisa into a modern highway, turning Hargeisa into a major transport hub for traffic from across the Horn of Africa to Berbera, which in turn would become a key import-export terminal for goods and commodities. This investment, one of the main achievements of the current government in Hargeisa, has the potential to bring significant revenue to the state, enabling infrastructure upgrades for both Berbera and Hargeisa, with flow-on effects for ancillary industries, and potential for increased employment. The Berbera project will create access for economic improvement in Somaliland while its demonstration effect is likely to bring further foreign direct investment, increasing impetus for international recognition. Likewise, the airport in Berbera—a military airfield designed in the 1960s by the Soviet Union and rented by NASA throughout the 1980s as a backup landing strip for the Space Shuttle—is, at 13,582 feet long, one of the two longest airstrips in Africa and its size and proximity to the port gives it potential as both an air cargo terminal and passenger hub, creating the possibility for a multi-modal terminal in and around Berbera, and an associated free trade zone. Several kilometres up the coast the United Arab Emirates is also currently constructing a military and naval base. This base—conceived as part of a network of regional bases being constructed by the UAE to support its ongoing engagement in the Saudi-led conflict in Yemen—brings a formal, permanent international military presence to Somaliland for the first time in its history. There is likely to be a modest local economic boost from the new base, but its real importance is political, placing Somaliland firmly in the Saudi-Emirati camp (rather than of Turkey, China, Iran or any of the other powers currently jockeying for advantage in the region). While some Somalilanders are understandably apprehensive about this, it is worth recognising that Somaliland has always—because of its dependence on animal exports to the Arabian Peninsula—been in this sphere of influence: the Emirati presence is a formalisation, rather than a revision, of the status quo. Nonetheless, a Hargeisa connected by highway to a modern port in Berbera, with a permanent international military presence (with its implied security guarantee) and strong transport links to regional and international trading hubs, will be a very different—and far less invisible—city than the Hargeisa of today. While this development carries huge potential benefits for Somaliland, like any rapid large-scale development of this kind, it also embodies risks that will need

careful management.

Observations and recommendations

This paper does not seek to tell Hargeisans—who know their own city best—how to develop Hargeisa or what to do about the many problems and opportunities that face the city. On the contrary, the strongest impression during our months of preliminary research and weeks of fieldwork was of a city, and of a group of townspeople, officials, community elders and business leaders who are justly proud of what they have achieved, know exactly where they want to go, and have a good idea how to get there. At the same time, not everyone in Hargeisa has the same experience, sees reality from the same viewpoint, agrees on the relative priority of particular issues or sees the same solutions. Thus, in this final section, each of the observations and recommendations that follows is derived from insights communicated by one or (usually) several locals. These are included as a way of sharing insights, playing back to the community the key ideas that respondents highlighted, as a basis for future discussion and decision-making—among Hargeisans only. For ease of reference, recommendations and observations are broken into the categories of national framework, physical infrastructure, financial and administrative development and human capital.

National Framework

• Encourage, but don’t wait for international recognition. Many government officials, and most business and community leaders, understood the negative impact of lack of international recognition on Somaliland, and on Hargeisa. However most also recognised that recognition will not, in itself, solve all of Somaliland’s problems—

on the contrary, as noted above, it may bring new ones. The Berbera port project and newly-invigorated relationship with the UAE, and the prospect of a larger role for Hargeisa and Berbera as regional export hubs, gave many respondents hope that the situation may be resolved. At the same time, all recognised that sitting around and waiting for recognition is not an option, and thus the following observations and recommendations all represent actions that can be taken now, which will help make the case for international recognition or, at the very least, not hurt it.

• Upgrade coast guard, law enforcement and military (in that order). Somaliland’s main contribution to regional peace, stability and safety of life at sea (SOLAS) is through its coast guard’s role in policing and maritime safety in the Gulf of Aden. Likewise, for most respondents, Somaliland’s police were well-respected and generally seen as lacking in corruption, albeit also lacking in modern equipment.

Somaliland’s armed forces—currently engaged in security efforts in the country’s east and south, preventing al-Shabaab or other militants entering the country in force, and enforcing Somaliland’s claim to its eastern Sool and Sanaag regions—are the least visible security for Hargeisans, while also absorbing a substantial chunk of the national budget. Efforts to upgrade the coast guard, with modern patrol boats, better maintenance, aircraft (perhaps leased or contractor-operated in order to meet the terms of the arms embargo) and mother ships allowing them to operate further offshore, would help Somaliland’s case for international recognition. Likewise upgrades to the police (including patrol vehicles, education and training, radio communications, investigative and forensic capability) would further improve public safety in the cities, helping to encourage tourism and foreign business presence. The lowest priority, though likely to be positively affected by the new UAE base near Berbera, would be the armed forces.

• Consider taxing remittances and leveraging diaspora investors. As noted earlier, at the national level remittances represent one of the country’s largest financial inflows, and are a critical connector between Hargeisans within the city and those in the wider diaspora. Several respondents agreed that the government should consider imposing a modest levy (on the order of 1-1.5%) on incoming remittances, combined with a clear commitment for this to be spent on public improvements (roads, water, electricity) and human services (health and education). Others argued that providing individuals and families in the diaspora with an opportunity to make an investment in a general health, education or infrastructure fund, or to contribute to a nationallyapproved investment vehicle, might provide a means to better leverage investment capacity within the diaspora.

Physical Infrastructure

• Secure and accessible water supplies. As noted earlier, water for the city of Hargeisa remains a critical commodity and one that Somaliland’s arid climate and uncertain rainfall renders precariously insecure. Further, in rural areas, since livestock depend on rain-fed pasture and farmers rely overwhelmingly on rain-fed (rather than irrigated) crops, drought in the hinterland can drive substantial rural to-urban migration and a flow of displaced persons into the city, where they impose further pressure on already stressed water supply systems. Besides the lack of overall capacity in the water system, several respondents cited the variability of access to water—with many new arrivals, displaced persons and slum dwellers having little or no access to water. Moves are afoot, as noted above, to build a town water system over the next 3-5 years to remedy this situation. However, many respondents noted that however effective the water distribution system may be, the overall availability of water is likely to remain a critical concern for the foreseeable future, as the city continues to grow. Several respondents also pointed out that the current cart- and tank-based water distribution system employs several thousand people in the city, many of whom will lose their jobs when piped water becomes widely available. Companies that own and operate water tankers will also see a substantial drop in revenue, so finding jobs for displaced workers (and alternative markets for water distribution) will be a critical market need.

• Reinforce efforts to improve agricultural security. Second only to water, food insecurity poses the most significant challenge for Hargeisa. As noted, Somaliland relies almost entirely on imported foodstuffs. Less than 10% of land is suitable for agriculture, and only 10% of arable land is irrigated, while the rest is rain-fed. Most farm production is subsistence-based, with the sole (and recent) exception of watermelons, now a successful export to Djibouti. Most farmers grow sorghum or maize for household consumption on small farms of 2-30 hectares, while fruits and vegetables are grown in market gardens for sale to cities.38 Several respondents emphasized the need to invest in agriculture, both for structural reasons (discussed earlier), and to remedy food insecurity and mitigate the resulting risk of population displacement and urban stress. Investors and donors might wish to reinforce the Somaliland government’s recent, sensible move to create a National Cereals and Produce Board, to co-fund a 767-hectare agricultural project west of Hargeisa that grows wheat, millet, maize, beans and sesame, and to construct silos to stockpile produce as an insurance against famine in both rural and urban areas.

• Increase renewable power generation. Hargeisa’s dependence on diesel fuel and gasoline (one hundred percent of which is imported from outside Somaliland) to operate electrical generators is another key challenge which many respondents identified as an obstacle to the city’s economic development. Moving away from diesel-powered generators toward wind, solar and other renewables is one option; developing the country’s oil and gas reserves is another. Most respondents agreed that both are needed: since renewables are unlikely to meet the demand as the city continues to grow, their principal role is as a means of reducing demand on imported oil and gas during the decade or more that it will take to develop Somaliland’s own resources. Household-level solar panels and wind turbines represent the lowest tier on the renewables ladder, with larger-scale projects (like the wind turbine farm under construction near Hargeisa airport, or the installation of larger fields of solar panels in and around the city or on rooftops) are the next step up.

• Transition cooking fuels to natural gas. A related issue is the use of charcoal and bottled gas for most household cooking in Hargeisa. Apart of the environmental degradation occasioned by the charcoal trade, the ongoing UN embargo makes charcoal supply precarious and several respondents felt that indoor and outdoor air pollution resulting from charcoal-based cooking was also a public health issue. At the same time, it is unrealistic to expect the vast majority of Hargeisans to move away from charcoal cooking until alternative sources—principally clean-burning natural gas, whether piped or purchased in cylinders—becomes widely available at a reasonable price. As the city continues to grow, demand for natural gas will grow with it, and companies like Somgas (with sufficient external investment and access to increased domestic sources of gas) are likely to prove important and valuable contributors to the city’s future.

• Improve roads and drainage. As mentioned, the poor quality of Hargeisa’s roads imposes costs—in time, maintenance, distribution chain inefficiencies and lost business opportunities—and discourages investment and new business in the city, due simply to the difficulty of getting around and doing business. The government’s efforts, through public-private partnerships, to improve road surfacing (and deal with the related serious issue of drainage and erosion) were appreciated by many respondents, but most felt more could be done. As Hargeisa becomes a more important transportation hub, and with the completion over the next several years of the Berbera-Hargeisa highway project (under the DP World Berbera agreement), Hargeisa’s lack of quality roads will create a bottleneck that could hurt the country’s overall economic development, as well as that of the city, and this may generate the impetus for a planned investment (by the government or external stakeholders) in the city’s roads.

Financial and Administrative Development

• Offer a conventional banking option. Several respondents—including local business owners, government officials, and visiting external investors—expressed the need to complement existing Islamic banking systems with a conventional banking option to enable business loans, credit purchases, creation of local investment funds and other financial services currently not available (or available only with considerable difficulty) to businesses in Hargeisa. While no respondent suggested that Islamic banking should not remain a key part of the city’s financial infrastructure, and all agreed that companies like Dahabshiil play an important and valuable economic role in Hargeisa, most agreed that a conventional banking option would open up opportunities for faster and more equitable economic growth and business development in the city.

• Integrate mobile phone systems. The penetration of mobile phones, the internet and satellite or microwave-based communications systems has been one of this century’s success stories in Somaliland, as in the rest of Africa. Enhanced connectivity not only creates the “greater Hargeisa” city system that drives much of Hargeisa’s development by connecting the city with its overseas diaspora, but also enables the global and regional trading economy that underpins the city’s growth. That said, respondents were universally frustrated by the inability of different mobile networks to talk to each other, by the need to carry multiple phones or SIM cards, and the lost time and cost to business involved. This issue (like the next one) is closely tied to that of international recognition, so there is little that individuals in Hargeisa can do about it for the moment, but continuing to highlight the issue makes sense, given the hindrance it continues to impose on the city’s growth.

• Consider a city internet domain. While Somaliland remains unrecognised (and while its independence continues to be opposed by Somalia) it is unlikely that the country will gain a national internet domain that would enable Somaliland-specific email addresses (e.g. “gov.sl” or “com.sl”). Most respondents appreciated the creative work-arounds that different government agencies and businesses have found in response. One respondent noted that the internet domain “Hargeisa.net” remains available, and that a Hargeisa-centric internet portal might make sense for economic and governance development within the city.

• Develop a functioning postal system. Since Somaliland remains unrecognised by the International Postal Union (IPU), as noted earlier Hargeisans have to rely on the slow and expensive DHL service, give letters to travellers to hand-carry and post overseas, or use internet-based fax and related systems. While several respondents recognised that the lack of a postal system has contributed to the explosive development of internet-based and mobile connectivity in the past decade, certain

categories of mail—including parcel post, shipping of goods purchased through online shopping, and some kinds of certified mail—would make a huge difference to the economic and business development of Hargeisa. Government might wish to consider creating a functioning internal postal system that meets IPU standards, even though not yet connected internationally, so as to enable the national internal system to be connected globally when the situation allows, and to enable economic growth in the meantime.

Human Capital Development

• Begin Benchmarking Human Capital. Neither Somaliland nor Somalia is listed in the latest Global Human Capital Report (GHCR, 2017), nor is Somaliland likely to be listed while it remains unrecognised. Still, the framework established in this benchmark global report—which categorises human capital across capacity, development, deployment and know-how—was recognised by several participants as a useful model for developing human capital at the national and city level, as well as for comparison with other countries in the region (including Somalia and Djibouti, currently not measured in the GHCR, and Ethiopia which currently ranks lowest among large-population countries in sub-Saharan Africa).

• Leverage construction and transportation industries to develop a skilled workforce. With Hargeisa’s ongoing construction program (including several commercial properties as well as residential structures) and the road construction and transportation industry opportunities—including maintenance, fuel supply, terminal operations, materiel handling and other growth opportunities—associated with the Berbera project, several respondents recognised the opportunity to exploit these initiatives as a way of developing a base of vocational and technical skills in the city’s workforce. With unemployment running particularly high, given the largely subsistence-based and informal khat sectors of the economy and the impact of the recent drought, the capacity to provide skills training and temporary employment to a substantial number of people (with permanent employment thereafter for a smaller workforce) was clear. Some respondents thought these industries could be leveraged to develop a skills base in the economy which would then flow on to future opportunities.

• Education, Skills and Training. Education in Somaliland has seen significant growth, with several universities and higher-education colleges in Hargeisa and numerous language schools, vocational skills institutes and private schools. This sector is ripe for further development, but respondents recognised that without an economy capable of absorbing higher-skilled graduates, improvements in educational capacity may simply result in higher rates of emigration into the diaspora

or across the region (since graduates will have no jobs to go to) or, in the worst case, may lead to unrest and agitation as a large class of educated but unemployable youth emerges. Most respondents therefore thought that sequencing education and skills creation in an integrated fashion with economic development would be an essential element of any national or city-level education and workforce development plan.

• Public Health. Likewise, most respondents recognised that efforts in the public health sector would need to be coordinated with economic and educational developments, lest improvements in infant mortality (currently one of the highest in Africa) lead to a youth bulge with negative consequences for educational and employment opportunities and social cohesion. No respondent thought this was a reason to delay action on public health—on the contrary, all felt that public and private medical and hospital services, health extension programs and clinics needed greater investment for humanitarian reasons—but it was clear that these necessary efforts should be synchronised with increases to educational and, subsequently, employment capacity.

• The Diaspora “Brain Gain.”41 As noted earlier, the “brain drain” of individuals leaving Hargeisa for the diaspora, being educated overseas, acquiring human and financial capital and then returning to assist in the city’s development, creates the opportunity for a “brain gain” where workforce skills, economic and investment

capital, and entrepreneurship within the city could be jump-started by carefully leveraging the returnees (or by establishing ongoing supportive relationships with Hargeisans remaining in the diaspora). However, as also noted, the return of wealthy and educated Hargeisans from the diaspora, and their dominance of political, civil service and business roles, creates the potential for resentment and marginalization of those Hargeisans who remained and suffered through the past several decades of conflict and reconstruction. A conscious, thought-through and carefully socialized policy on leveraging diaspora capabilities in order to benefit all Somalilanders was an idea that most respondents fully supported.

Conclusion

Hargeisa—both the physical city in Somaliland, and the larger invisible city with a global presence and a worldwide network—is a growing, dynamic, safe and vibrant place. The city is confident, building on 28 years of self-help and bootstrapping, and is ready to take its place as a major regional economic and trading hub. While the issues and problems associated with lack of recognition are real (and have been discussed in detail), the city’s future is bright, and there are many things Hargeisa can do to accelerate economic and social development without waiting for the world to recognise its progress. For those in the diaspora who fled in the 1980s or grew up overseas since, the city is a welcoming presence; for the region and the world, Hargeisa is open for business. With engagement, patience, and a recognition that Somalilanders have done extremely well on their own, the opportunities for growth, development and resiliency in this city are clear and waiting.