Somaliland’s Industry at a Crossroads

Somaliland’s Private Sector at a Crossroads

Background to the Somaliland Private Sector

The Setting

Somaliland’s private sector has thrived in many ways since Somalilanders chart- ed a path out of the destruction inflicted on the region during the Siad Barre regime. The extent of its revival since 1991 is a testament to the Somaliland people and their entrepreneurial and business culture. The private sector, part of a broad set of businesses anchored in the agropastoral, telecommunications, trad- ing, and financial/remittance sectors but also in provision of social services, has rightly been acknowledged for its resilience and contribution to an economy and people that experienced massive dislocation and privation prior to the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991. By then, the capital city of Hargeisa had largely been reduced to rubble, with an estimated 70 percent of the city destroyed, some 5,000 people killed, and 500,000 people internally displaced.

Since this time and in parallel with an extraordinary effort of Somalilanders to rebuild the region and establish a legitimate and viable government institutional structure, the private sector has shown a level of innovation, vibrancy, and capacity for investment risk that has been rightly lauded as fundamental to the success story that is Somaliland.

The Size and Structure of the Somaliland Private Sector

GDP Shares: The continuing significance of the private sector to the Somaliland economy is most immediately evident when viewed in terms of GDP shares. Reliable economic statistics on the Somaliland economy are limited.

Electricity

Electricity costs are roughly US$1 per kilowatt hour leaving most (~65 percent) micro- enterprises and HBBs without access to electricity. In fact, HBBs are four times less likely to own a generator and nearly 20 percent less likely to have access to a private electricity source. Eighty-two percent of firms in Berbera are served by public electric utilities. But this is the exception. Only 13 percent of firms in Hargeisa get electricity from public sources, while the remainder of the busi- nesses in Somaliland rely entirely on private sources for electricity, mostly in the form of diesel generators. Firms cite relatively infrequent power outages—only four per month for a total of 8.8 hours of outage in a typical month (note that regular scheduled outages, load shedding, and changeover were not counted in this figure). This may not reflect the full nature of the constraints posed by elec- tricity, as firms may compensate by adjusting expectations and operating in low electricity-intensive industries. Improvements in electricity infrastructure would have significant positive economic development impacts. Efforts to encourage the development of safe, reliable, and less expensive energy should be a priority for fostering economic growth because of its potential effects both on quantity of economic activity and on the scope of viable businesses that can thrive with improved electrical access.

Female-owned Businesses

Evidence in Somaliland strongly suggests that firms with women in top positions tend to have a higher proportion of female workers than other firms. One reason for this could be that women in top positions tend to open doors for other female workers. It is also possible that certain types of jobs or sectors that are more favor- able to women tend to attract female managers and owners as well as employees. For either of the two or other reasons, the proportion of females in the workforce is significantly higher in Somaliland among firms with a female largest owner than a male largest owner (43 percent vs. 7 percent). The result holds separately for the sample of micro, small, and large firms and also for manufacturing, retail, and other service sectors, with the exception that large firms have a roughly similar percentage of female workers irrespective of the level of female ownership. Firms with female ownership are also far more likely to be formed as partnerships than male-owned firms. Discussions with a number of female business owners suggest that while females are not constrained in how they form businesses either by laws or by social norms; they are often constrained by costs and family responsibilities. Partnerships allow women to share the costs, risks, and responsibilities associated with starting and running a business by pooling resources.

Regardless of the reasons why women tend to work for and with other women, it is important to note that female-owned businesses in Somaliland are the primary driver of female employment in the economy and are therefore critical to the wellbeing of women in Somaliland. Improving female participation in eco- nomic activity is important not only for improving the economic condition of women but also for overall economic development and growth. To strengthen female involvement in the market and in enterprises, particular attention needs to be paid to correct for distortions that impact their productivity. For instance sales growth is strongly and inversely correlated with the presence of females among the owners.

In summary, businesses with higher female ownership tend to have proportionately more female employees in the workforce, to be smaller in size, and to be less productive. What explains the difference? Relative to male-headed firms, female-headed firms are characterized by less access to “formal” finance, are less experienced as managers, and are generally less well educated or trained.

Incentivizing Business Formalization

The vast majority of businesses operate informally with only an operating license or occupancy permit issued by the local municipal government. The government’s perspective on formalization is that it presents an opportunity to foster greater growth and employment creation; enables the government to achieve a wide range of social benefits, including in the health, safety, fire, pension, labor, and environmental areas; and contributes to the tax base and revenues needed for the operation of critical government services. On the business side, the over- all stakeholders’ perspective as revealed in interviews and discussions was that the cost and burdens associated with registering formally outweigh the benefits.

Changing this cost-benefit ratio for businesses requires a re-calibration of regulatory reform that makes possible more cost efficient formalization (that is, minimizing time and cost) and links this improved formalization process with better access to new services that can enhance firm performance and the return to investor and manage- rial effort.

Berbera Port Development

The Somaliland domestic market is relatively small. It is also highly dependent on regional and international trade, particularly in terms of imported consumer and intermediate goods

Financial Inclusion and Product Diversification

The Financial Sector in Somaliland

The private sector remains constrained by a multitude of blockages which inhibit the market competition and the potential for growth that could foster investment, reduce costs, and improve quality and availability of basic products and services. A key service sector is that of finance, where access is the highest ranked constraint faced by businesses.

Remittances

Large remittance inflows to Somaliland help families pay for food, education, and health services. They support small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) development, also connecting entrepreneurs in Somaliland with business partners from among the diaspora. Remittances also have major macroeconomic implications, financing imports and underpinning the local money supply.

Estimated Volume and Impact: Although the GoS estimates that some 150,000–200,000 Somaliland-born migrants are living abroad,3 this figure could be substantially underestimated. It is difficult to determine a precise figure because other data collection sources on migrants do not count those from Somaliland separately from Somali migrants. Official statistics estimate that the Somali diaspora amounts to an estimated 1.9 million people living in the Republic of Yemen, Western Europe, North America, and other parts of the Horn of Africa in 2013,4 with Kenya, Ethiopia, and Yemen believed to be the primary destination countries. Somaliland diaspora could be closer to average 600,000–800,000 or between 1.2 million to 2.1 million diasporas.

Remittance flow process: Transfers from the diaspora tend to be small and regular. The most common transaction size is about US$100, but the average remittance amount depends on the sending country; average transfers from the United Kingdom could be as little as Great Britain Pounds (GBP) 25 per person compared to US$170 for those originating in the United States.8 Reported costs for making remittances to Somaliland are generally 5 percent of the amount sent up to US$1,000.9 This is well below the total average cost of transferring funds along corridors to Africa, which was reported at 11.7 percent to send about US$200 in the first quarter of 2014, according to Remittance Prices Worldwide (RPW—a World Bank database that tracks the cost of sending money along 226 corridors, globally).10 It is also below the global average cost of sending remittances, which was 8.4 percent over the same period.

To get a direct sense of the costs and processes of sending money to Somaliland, two remittance payments from different outlets in London, United Kingdom (see table 4.2) were initiated. The results confirmed that the price of transferring money to Somaliland is relatively inexpensive—about 5 percent.

Transaction process: The overwhelming majority of remittance transfers are facilitated through specialized Somali MTOs established in the late 1990s and

Policy Priorities for the Financial Sector

The challenges facing Somaliland in building an effective financial sector remain significant. However, the authorities can benefit from extensively known best practice to build a diversified, inclusive, credible financial sector that supports a level playing field for market participants and protects consumers from abuse. This system can be tailored to comply with well-defined Islamic principles.

The Government Regulatory and Promotional Role

The Government Sector in Somaliland

In any economy, the government is a critical provider of services to business. At a minimum, it needs to provide macroeconomic stability, policy development, infrastructure (where it cannot be provided through private investment), and a legal framework, with secure contracts, property rights, supportive regulations for enterprises and banking, and an ability to enforce those regulations. In a postconflict economy or in a developing economy where there is a particular need to stimulate investment and growth, there is also a premium on a proactive promotional role in the provision of fiscal, financial, and nonfinancial support. As has already been seen in the case of financial inclusion, the challenges to government legislative, policy, and implementation capacity are substantial and greater when set in a context of fragility with political, technical, and financial resource constraints such as those faced by the GoS. Selectivity and sequencing will therefore play a central role if an optimal path of regulatory and promotional capacity development is to be achieved. A first step in mapping out the role and needs of the GoS in private sector engagement is to provide an assessment of the capacity of government institutions to support private business. That is, to assess the arrangements in place, GoS has to (a) regulate and (b) promote PSD activities and identify key areas for institutional change and capacity building as economic recovery and development proceeds.

The small size and relatively low capacity of the present government administration is largely a product of the civil conflict that started in 1991 with the collapse of the Somalia state that had existed under the Siad Barre government. This resulted in a destruction of infrastructure, a significant decline in private business activities and tax revenue and a lack of government authority and effective regulation. This was in contrast to the period during the 1970s and 1980s when there was intrusive state control of the productive sector through direct ownership of production capacity and heavy regulation. Over the past 20 years, the government’s regulatory authority has slowly recovered, but its promotional role is, as yet, hardly developed.

Development of a Capacity-building Strategy

The need for capacity building to regulate and promote private business: While first steps have been taken, much remains to be done. The institution building strategy going forward will need to achieve more of a balance between the revenue-generating needs of the government and the promotional needs of private business. While regulatory functions are being developed, they remain weak and training and equipment needs are considerable, not as much in the licensing and taxation areas but particularly so in the supervision and inspection areas. The private sector promotion functions of government, whether fiscal, financial, non- financial, or in regard to broader factor market issues, such as financial sector development and employment promotion, are still further behind. Physical constraints such as rapid urban growth are also putting considerable strain on start- up government services.

Capacity and training needs of key agencies: Comparing the government ministries’ regulatory capacity self-assessments with their importance in addressing the key obstacles facing business, the main need for capacity building is in supervision and enforcement and in monitoring and inspection. Some, notably the Ministry of Commerce and Investment also assessed themselves as weak in the policy area. The Ministry of Energy was the only ministry dealing with key obstacles to business that also rated itself ‘satisfactory to strong’ in supervision/enforcement. In the promotional area, the information pro- vided suggests that there was weakness across the board, and the area where a number of government ministries felt the greatest need for capacity building was in forming PPPs.

Policy Priorities for the Government Sector

In an economy so reliant on its private sector, much still depends on the accelerated development of the government sector and its capacity to develop, introduce, and credibly implement key institutional, legislative, and regulatory arrangements. Added to this is a clear role to collaborate with the private sector to undertake promotional initiatives to address market failures that hinder private sector risk taking and investment. Recalling the priority areas set out in the earlier section on business demand for government services and those actions recommended in the chapters on the enterprise and financial sectors, table 5.6 provides a summary of key capacity building requirements in order for government to be able to address these priorities. This summary draws also both the survey results from the government ministries and other agencies and the ministries’ own published plans. It represents a considerable development program.

Going forward, the insight that local government has a specially broad engagement with private business on both the regulatory and the promotional sides10 suggests, in particular, that the government’s role in private sector development in Somaliland requires not just a careful consideration of the future balance of regulatory and promotional action, but also the future balance of central and local government action. A large part of the responsibility could beneficially focus at the local government level. This especially applies to activities such as business licensing, inspections, and enforcement (for example, of industrial pollution controls), settlement of land disputes, development of commercial and industrial space and services, improvement of urban or ex-urban access roads, water, provision of business support services, participation in PPPs for infrastructure development and service delivery, and dialogue with the private business community.

In the short to medium run, adequate capacity does not yet exist in the municipalities to carry such a burden of broad business regulation and support programs. So for now, the initiative for new support programs will need to be taken at the central level. The main exception is in the critical area of land use, where there will need to be a demarcation of responsibility between the Ministry of Public Works, other central ministries, and the municipalities. However, in the longer term, the way ahead may be for the government to delegate significant

Economic Governance and Political Economy Choices

The Evolving Challenges to Somaliland Economic Governance

For the purposes of this report, economic governance is understood in the following terms as the “structure and functioning of the legal and social institutions that support economic activity and economic transactions by protecting property rights, enforcing contracts, and taking collective action to provide physical and organizational infrastructure” (Dixit 2009, 5). Economic governance is both a major responsibility of government and the point in public policy processes where political and economic interests directly intersect. Getting economic governance right is a critical prerequisite for sustained economic development. Among other things, it requires the following:

- Passing appropriate legislation and tailoring policies to create an enabling environment for private sector growth while also protecting consumers, workers, and the state.

- Developing a tax code that is perceived as fair, that is enforced universally, and that provides the government adequate funding to operate without im- posing undue burdens on firms and citizens.

- Developing sufficient governmental capacity to implement policies and regulate the economy.

- Ensuring that government is accessible, responsive, and accountable to citizens without being captured by particular interest groups.

Given its current regional status, recent history, and deep and long-standing clan-based and political culture, Somaliland has a unique set of factors at play that impact the current status and potential evolutionary path of its economic governance arrangements. These need to be understood in order to more effectively identify the challenges and opportunities to economic governance appearing on the horizon.

The limits of informal governance: Earlier in this report, the strengths of the Somaliland economy were noted and in particular the capacity of Somaliland to establish economic exchange through a trust based on social and cultural mores. But as the economy progresses and strives to meet the more complex demands of a maturing and growing population, the negotiated, informal arrangements that have served Somaliland well in earlier postwar years are increasingly shown to be insufficient for its next stage of economic growth and investment. The signs of this changing reality are revealed in the analytical work undertaken for this report. Somaliland ranks among the most difficult places to do business in the world (World Bank 2012, 1). The ESs identify a range of factors that impede or discourage private sector investment. These obstacles are further confirmed by the diaspora dialogues and the consultations that accompanied the analytical effort.

Looking more deeply at the leading constraints such as finance, land, and water, of note is the differential impact that these constraints have on different strata of the private sector. For instance, small businesses reported different experiences of investment constraints than larger businesses; female-headed firms face additional constraints to their productivity; and diaspora expressed concerns that their capacity to invest is hindered by perceived uneven treatment in some areas, such as access to land and dispute resolution. A general finding is that large enter- prises are in a much stronger position to address and resolve impediments to doing business in Somaliland than are small firms and microenterprises. Large businesses can gain access to credit abroad, procure their own power, import skilled labor, and use their money and social capital to ensure land disputes are resolved in their favor. Large firms enjoy certain advantages in all economies but are arguably in an even more privileged position to benefit from the current system of negotiated arrangements with the government. Smaller firms have weaker bargaining positions with the government and complain of inconsistent and costly administration (for example, in customs), which breeds distrust of the government and animosity toward what is perceived to be the potential for collusion between large firms and the government.

In several sectors (for instance, import–export, telecommunications, and remittances), the potential exists for more powerful businesses to shape public policies in ways that can discourage or prevent new competition in those sectors. As has been portrayed in the foregoing chapters, the government currently has a limited legal, regulatory, and institutional capacity available to deal with this dynamic. This leaves the government ill-equipped to properly manage the issues and maintain its accountability to the wider population. The worst-case scenario is one where there is policy capture, which can severely reduce government legitimacy as steward of the public interest. This is not an issue easy to address in Somaliland, given the current lacuna of objective data and the ever-present concern not to diminish the track record and huge strides that have been taken— by both public and private sectors—since 1991. However, interviews and focus group feedback consistently voiced this concern. Somaliland does not want for engaged political discourse among its citizens, so it is not surprising—given the size of top private sector firms in Somaliland in contrast to the modest capacity of the government—that concerns about government autonomy on critical matters of economic governance are being raised. If these concerns are not objectively addressed with evidence and transparency, there is a risk of eroding public confidence in the otherwise impressive democratic system in Somaliland.

An imperative for institutional development: To take advantage of current and future economic opportunities, especially nonremittance external sources of investment, Somaliland must accelerate its transition to greater reliance on formal economic governance tools and uniform application of laws and policies. If not, Somaliland risks becoming trapped in economic governance arrangements that will produce a low-level equilibrium and missed opportunities, as well as declining political legitimacy. Informal, negotiated arrangements between the government and private sector actors or between private sector firms pose too many risks for investors. These arrangements work against new investors with little or no social capital in Somaliland which, in turn, is currently the primary source of the trust relations at the heart of Somaliland’s current political economy.

Overall the evidence to date signals an institutional-building effort that has made progress in developing formal structures of economic governance. However, where much remains to be done within this framework. For instance, the legislature’s ability to understand and address complex technical aspects of economic governance is variable. Moreover, the formal judiciary is not relied upon by most citizens and firms to adjudicate disputes or enforce contracts. At the level of the executive, there was—during the consultations and interviews— views expressed that the presidency role in decision-making needs to be put onto a more formal institutional footing. At the level of the Somaliland government— as portrayed in chapter 5— “clusters of competence” exists in a variety of offices and ministries, but generally the capacity of the civil service to implement and enforce policies is low. The effectiveness of ministries and municipalities typically depends on the quality and commitment of one or two individual leaders, so cabinet rotations can have dramatic impact on the quality of a ministry’s performance. This is not a surprising finding, as political institutionalization is a slow process that can, even in best case conditions, take a generation and longer. In the absence of a sufficiently professional government institutional capacity, a government can be more easily penetrated by strong societal (clan) and private sector interests. All this in turn impacts the center–periphery dynamics and the impact of the election cycle. Some comments on each of these factors follow.

Clannism. Somaliland is a lineage-based society in which clan and subclan identity play an important role. Clan has an ambiguous role in Somaliland. On one hand, the social contract between clans has been central to maintaining peace, and clan-based customary law has been the main source of routinized dispute management. On the other hand, clannism can work against the principle of meritocracy in employment and contract distribution, encourage neo-patrimonial behavior, and is at the heart of some of the most intractable disputes over property and rights. Clannism is ubiquitous in Somaliland politics: the role of clan elders is institutionalized in the Upper House or Guurti; citizenship is based on

clan; voting strategies are heavily influenced by clan calculations designed to maximize the number of seats a lineage has in Parliament; an informal under- standing has been in place that the presidency rotates among major clans and subclans; the Ministry of Labor sometimes reviews hiring practices to ensure acceptable distribution of jobs along clan lines; and the ongoing tensions in eastern portions of Somaliland.

Core-Periphery Dynamics. As with Somaliland’s informal economic governance arrangements, the aspects of clannism that helped Somaliland maintain peace and stability now risk becoming an obstacle to good governance and private sector growth as Somaliland enters a new phase of development. This tension is liable to intensify if the government is unable to diversify its economy, not just in terms of greater access to opportunity in different sectors of the economy but also geographically. Economic investment and wealth are heavily concentrated in the capital Hargeisa and more broadly in the Berbera-Hargeisa-Boroma corridor. Most of the rest of Somaliland has seen limited development. Lineages that are dominant in the core area have benefited more from Somaliland’s private sector investments. A concerted effort is required to mitigate the perception and evidence of privileged access and build a more inclusive private sector development paradigm.

Democracy and elections. Somaliland’s multiparty democratic system is another impressive accomplishment. Election campaigns are, however, an important entry point for powerful private sector lobbying in the political arena. Parties and top political figures accept contributions from large firms which, in the absence of clear legally enforceable rules for accepting and using election contributions, leave open the perception that preferential benefits are involved. These arrangements are a source of frustration for smaller businesses.

Managing Change with Structural Transformation

The case for the status quo: Somaliland is a high-risk investment environment due in part to its unrecognized political status and the complications that this creates. The research done for this report confirms that local private sector actors have done an impressive job of both calculating and managing risk primarily through traditional mechanisms, given the limited institutional and regulatory structures built to date, albeit from a very low postconflict base. It has also led to caution towards stronger economic governance measures that create new uncertainties, by altering an operating environment in which many in the private sector have found a level of security and in which a significant number has managed to thrive.

Given this context, pursuit of more robust economic governance will need to include a focus on producing shorter-term positive impacts to reassure businesses of the long-term value of an effective regulatory environment. Nevertheless, the outstanding political economy question that bears close monitoring is whether the current informal institutional arrangements

and policy-making practices of the Somaliland government are viewed as a transitional state, or as a preferred condition to satisfy the interests of those that would want to perpetuate in an operating environment of informal governance. The present evidence is mixed, suggesting that initiatives to promote new modes of more formal governance will be the source of both support and con- test within civil society, the private sector, and government itself. The challenge is likely to become even more complex over the coming years as potentially transformational economic developments could significantly impact the eco- nomic and policy interests among Somaliland’s key stakeholders.

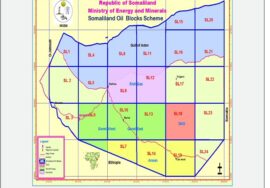

Sources of change: Three economic developments in particular—hydrocar- bon extraction, expansion of the seaport, and expanded transit trade with Ethiopia—have the potential to reshape the Somaliland economy, creating a significant increase in government revenues, attracting large direct foreign investments, and creating new opportunities in information and service sectors. This foreign investment is already starting to flow with the recent investments by foreign firms including Somcable, Coca-Cola, and Genel Energy. Port and transit trade expansion and the discovery of hydrocarbons could rapidly accelerate direct foreign investment, potentially bringing with it needed capital investments, technology transfer, and job creation. It will also add a powerful new dimension to the political economy equation.

The other consideration to note is that these developments have the potential to change the Somaliland economy into what is known as a “rentier” economy— one in which most government revenues accrue from the “rent” it captures from natural resources or real estate rather than from taxes on citizens. This can have the effect of shifting the commanding heights of an economy from the private to the government sector. The pathologies of rentier states are well known, often linked to the so-called resource curse, and serve as a cautionary note. In the wrong circumstances—conditions of low levels of institutionalization and accountability and low commitment to national development—rentier states can result in spikes in corruption, authoritarianism, and power struggles. When governments with strong rule of law, accountability measures, and commitment to the future are in power, windfall revenues from natural resources and seaports and DFI flows are more likely to be harnessed to promote rapid economic growth and political stability in the interests of the Somaliland people.

In addition to the new sources of economic growth now appearing on the horizon, questions can be asked about the future of the current mainstay of the economy—the remittance flow. Few diaspora in the world are as dedicated to remitting money to family members on a monthly basis as are Somalis and Somalilanders, a unique advantage that reflects the powerful obligations binding this diaspora to its extended families. But the fact that remittances constitute 40–50 percent of the Somaliland GDP is a worrisome level of dependence on an external source of funding that, while reliable, is vulnerable to disruptions due to economic downturns, changes in welfare programs in host countries, and banking regulations. It raises concerns about the long-term sustainability of the Somaliland economy. The finding that 40 percent of Somaliland households receive remittances, averaging US$271/month, and that the urban middle class remains dependent on remittances underscores that households receiving remittances form something of a privileged class in Somaliland. This system creates enormous incentives for households to focus their livelihood and investment strategies on placing a family member overseas, despite the very high cost and risks involved. Evidence from other research (for example, the UNDP Human Development Report of 2011) finds that the remittance-focused economy shapes educational choices as well, as young people pursue language and other skill sets mainly crafted to make them employable overseas. The heavy reliance on remittances means that Somaliland’s top export is its own labor force.

As the second generation of the diaspora that commenced in earnest in the early 1990s starts to earn a living, it will be of particular significance if this new generation of Somali immigrants and refugees are less willing to remit money to family members they barely know. This suggests that the remittance economy on which Somaliland is currently based is unsustainable without a continued flow of citizens abroad. Tightening immigration laws in the West and efforts to indi- genize labor in the Gulf could make this more difficult in years ahead. There is a possibility that the current generation of remittances constitutes temporary windfall revenue that will slowly decline in importance.

Whether Somaliland becomes more of a rentier than a remittance economy depends on factors like the size and extractability of oil and Somaliland’s ability to stay connected with the new generation of diaspora, both of which are largely beyond its control. What it can control is its preparations for such a scenario—the pace and effectiveness of policy reform and institution building. If Somaliland engages in the difficult task of economic governance reform now, it stands a much better chance of adapting to potential changes in remittance flows and harnessing new wealth from trade and oil toward transformational growth in the economy. Though the actual changes in the economy have not yet occurred, Somaliland today is at the “pivot point” in its economic development. In sum, Somaliland is approaching a critical crossroad; the decisions its leaders take on these matters will determine the course of Somaliland for decades to come.

Conclusion

The Political Economy at Work

Somaliland has already experienced two decades of major changes in its security situation, its political system, its economy, the regional environment, and technological changes. In the process, Somaliland and its people have demonstrated impressive resilience and capacity for progress—both politically and economically. The Somaliland of today bears very little resemblance to the Somaliland emerging from the war and dislocations of the early 1990s. Politically, Somaliland featured very significant adaptability and innovation in the 1990s, from the Boroma peace conference to the passage of the Constitution in 1999, which transitioned the government from a clan-based form of representation to a multiparty system. Somaliland also demonstrated its political adaptability with its hybrid governance model, which enshrined the role of customary authorities (clan elders) in the Upper House or Guurti. In a region with various forms of more authoritarian government, Somaliland has remained committed to a liberal democratic model.

Over the past 15 years, however, the political system can be seen to have grown less able to respond to changes in the economy, society, and wider region- al setting and is having difficulty keeping up with changes in the private sector. Everywhere, political institutions and governance models tend to be slower to adapt than their counterparts in civil society and the private sector, so Somaliland is not unique in this score. Politics is driven and constrained by competing inter- ests, compromises, and slow decision-making processes. In the case of contemporary Somaliland, the gap between the speed of potentially transformational changes in the wider political economy and the pace of the government response runs the risk of missed opportunities on a large scale.

From the political economy perspective, the analysis undertaken from this report points to the following conclusion. The principal impediment to business, as documented by the survey (including access for finance, insecure land title, costs of and access to infrastructure services) all reflect shortcomings in core economic governance. Additional concerns raised during diaspora and local business interviews that taxes and customs are opaque and unevenly applied further highlight the deficit in terms of policy focus and implementation. It is not just about the policy and legal framework but also very much about the capacity—both technically, but also politically—of government to implement in an even-handed, transparent, and predictable fashion and provide a level playing field to domestic, diaspora and international investors.

Private Sector Development and Jobs Creation—Policy Choices for the Future

Many rightly laud the more traditional coping mechanisms discussed in this report. It has provided the bedrock for much of Somaliland’s success to date. But the proposition of this report is that this model of economic development is reaching a point of significantly diminishing returns and an increasing inability to meet the demands of a population that is seeking opportunity and jobs and a closer integration with the world economy. There is an opportunity and necessity to generate a step-change level of new investment flows and to access new markets to spur broad-based economic growth. But it requires that Somaliland takes the dynamic and robust culture that has served it so well through very difficult times and joins this to a drive for institutional development and internationally recognized standards of economic governance.

This renewed drive towards objectives that the GoS itself has set out as policy goals in the SNDP would provide a clearer path towards a more robust diversified economy with greater capacity to provide the jobs that Somaliland requires. And while there are larger regional political issues to be addressed by the GoS, the private sector development policy options avail- able for pursuit at this juncture remain entirely within its purview. They can be acted upon now. This conclusion echoes recommendations from many other quarters for Somaliland to build its capacity to deliver economic gov- ernance and judicial functions through formal institutions and laws, and not via informal arrangements. This will involve a transitional period in which both formal and informal mechanisms play essential but overlapping roles. There are many risks associated with this transition, one of which is incautious policy initiatives that undermine informal mechanisms of economic governance and enforcement of contracts when they are still needed. The transition will require carefully calibrated legal and policy shifts implement- ed over time with careful management of the vested interests they will impact. What would be the core features of a policy agenda designed to respond to the greater international, regional, and domestic pressures that the economy will be facing in the coming years?

The following represents a summary of main priorities, as they pertain to the financial, enterprise, and government sectors that have been the focus of this report.

- Financial Sector: Somaliland needs to get its financial sector into better shape. It should pursue and conclude decisively on its current ongoing debate as to the nature of this sector and whether it is to be a solely Islamic financial or alternatively a dual system. Once this decision is made, move purposively to amend and introduce the necessary legislation so that an effective regulatory system can be operationalized, and this absolutely key sector can provide the inclusive services that the economy so desperately needs.

- Enterprise Sector: Facilitate formalization and new business entry and target services to those businesses with near-term employment and growth potential, including firms with a track record for innovation and female-headed businesses. Develop enterprise zones and industrial parks where it will be possible to mitigate infrastructure and land access risks more systematically. Ensure that these services are allocated to interested businesses in a transparent and accountable manner and in accordance with well-defined and documented eligibility criteria. The other key infrastructure investment priority is development of the Berbera Corridor. But this is not just about capital investment; it must also entail governance development and modernization of other key related services—in particular the customs administration.

- Government Sector: Ensure that capacity building to and investment in government and other public agencies (for example, the BoS and Berbera Port) are aligned closely with policy milestones, the passage of critical legislative instruments and regulations, and initiatives being taken for the enterprise and finance sector—as outlined above. Put in place a metrics program and align institution building and training closely to progress on these higher-level development outcomes.

Concluding Remarks

Somaliland’s maintenance of peace and security is a signature accomplishment and must be safeguarded. Conflict sensitivity is required in all aspects of eco- nomic governance to ensure that goals designed to catalyze private sector growth do not undermine Somaliland’s sustained peace. The World Bank’s World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security, and Development concluded that “strengthening legitimate institutions and governance to provide citizen security, justice, and jobs” is critical to breaking conflict cycles and maintaining peace (World Bank 2011, 2). It is significant that all three of these government deliverables are also central tasks of economic governance to promote private sector growth.

In its diagnosis of resilience and vulnerability to political violence, the report found the following:

Many countries face high unemployment, economic inequality, or pressure from organized crime networks but do not repeatedly succumb to widespread violence, and instead contain it. The WDR approach emphasizes that risk of conflict and violence in any society (national or regional) is the combination of the exposure to internal and external stresses and the strength of the “immune system,” or the social capability for coping with stress embodied in legitimate institutions. Both state and non-state institutions are important. Institutions include social norms and behaviors—such as the ability of leaders to transcend sectarian and political differences and develop bargains, and of civil society to advocate for greater national and political cohesion—as well as rules, laws, and organizations. (p. 7)

Applying the World Development Report (WDR) findings to the Somaliland case is revealing. First, Somaliland currently performs well in two of the three critical tasks associated with consolidated peace—provisioning of security and justice. It falls far short on the third objective of generating employment, how- ever. The legitimacy of its institutions is generally high, but threatened by some of the factors noted above, especially public perceptions that the government is too susceptible to private sector capture. The WDR makes the point that the societal “immune system” to political violence requires strong institutions at both the state and nonstate level. In the Somaliland case, informal institutions are currently more central than formal state structures to peace maintenance; this sug- gests Somaliland’s “immune system” is functional but incomplete, and that Somaliland’s ability to consolidate peace requires stronger governmental institutions.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the WDR is how it highlights a difficult transitional challenge in Somaliland. Strengthening of formal economic governance and capacity is needed to attract investment that will spark growth and reduce unemployment. But that needs to be done without compromising the constructive role that informal institutions have to date played in maintaining peace and providing justice. Somaliland’s strategy for pursuing formal economic governance will need to ensure that informal governance arrangements are not disrupted abruptly during the long transitional period of institution building. The continuation of pluralistic legal systems for dispute mediation is one example of how formalization of economic governance can be achieved in a conflict-sensitive manner, as part of an intentional transitional strategy designed to ease disruptions while shifting from informal to more formal economic governance.