Traditional Governance and the Modern State in Somaliland

Challenging the Ideal? Traditional Governance and the Modern State in Somaliland

ABSTRACT

Increasing attention paid to state-building and reconstruction of post-conflict states has highlighted significant deficiencies in the practice of state-building, largely brought on by a lack of knowledge and expertise, but also because of a narrow and intrusive view of what a state can and should be. By examining assumptions underlying much of the literature on weak, fragile and failed states, the myth of the ‗ideal‘ state is highlighted; through this it is possible to understand, and also critique, the expectations for state formation or state-building and what a state ‗should be.‘ An idea case study for this, and thus the focus of this thesis, is Somaliland, an unrecognised state in the Horn of Africa. For all pretences, Somaliland is a separate entity from its southern neighbour, and is often referred to as the ‗model‘ of state formation in Africa. However, Somaliland deviates from the normative values surrounding successful statehood in its inclusion of traditional authority in the central government. Whilst the hybrid government in Somaliland was created to establish peace and stability in the territory, pressure for democratisation of government institutions is creating tensions between the ‗old‘ Somali style of governance and the ‗new‘ democratic government in the territory; tensions which are becoming more apparent and problematic. This thesis examines these tensions and relates this case study to larger questions of not only state-building but also state formation; namely the impact and consequences of international norms of statehood on stability within new or democratising states. Somaliland shows the absence of international state- building projects and the ability to closely tailor the project to the specific case can facilitate the creation of the state, particularly in contrast to the ongoing succession of failed projects in Somalia, resulting in a project that reflects both internal and external demands and desires. In addition to highlighting and examining the successes of and obstacles to Somaliland‘s state formation project, this thesis comments on deficiencies in international intervention in developing, forming or re-building states as well as in the normative frameworks or blueprints concerning how to be a state.

Chapter 1: Introduction

While many of the existing territorial states in Africa remain fragile and prone to collapse, these conditions have not always given way to anarchy. On the contrary, in a few cases, the breakdown of large, arbitrary state units has given way to more coherent and viable (though not always more benevolent) political entities.

The 1991 failure and collapse of the state in Somalia ushered in what was to become a long-term and largely unsuccessful effort aimed at internationally driven post-conflict state reconstruction and state-building. Since 1992 Somalia has been the subject of numerous peace conferences and a succession of attempts at re-establishing the state apparatus and a government. The current government in Somalia continues to be plagued with difficulties, not only from within the government itself but also from various factions within society. The return of Somalia‘s government from more than a decade in exile in Kenya was not met with jubilation in the streets, but rather the continuation of violence so intense in the capital city of Mogadishu that the returning government opted to base itself in Baidoa, nearly 160 miles away. Today‘s unstable and unpredictable situation in Somalia leads one to question the sustainability of the current incarnation of the government and, more broadly, of an externally created government within the archetypal failed state that is synonymous with anarchy. Despite the persistent failures at re-building the state, the international community and Somalia‘s neighbours continue their endeavours aimed at building a stable and accountable Somalia. Where the international community is absent, however, pockets of locally created governance have emerged. In the northeast province of Puntland, along-standing regional government offers basic services and security to the

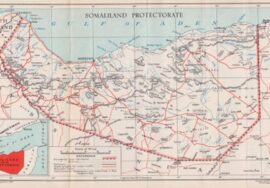

In many areas outside the major cities, clan governance continues to population provide social and physical stability and security to the people. And in the northwest territory of Somaliland, the most organised and developed of these pockets of governance, a new ‗state‘ that exhibits the central democratic government that has so far eluded the south is emerging. It is here that an extraordinary project of state formation is taking place within the larger failure of Somalia.

Throughout the literature on failed states and that of state-building, the on-going project in Somalia is a constant point of reference. Within these studies the self- declared independent territory of Somaliland is often referred to as a rebel region or as a deviant breakaway territory that refuses to engage with the wider project of reconciliation and rebuilding. Whilst it is true that there is a refusal on the part of both Somalia and Somaliland to engage with each other in negotiations or discussions on the nature of Somaliland‘s status, the attachment of the rebellious or deviant label creates a situation in which the causes for Somaliland‘s secession and the successes in creating a state are not acknowledged. Instead, the existence of an independent Somaliland is problematic for the long-standing goal of re-establishing a government able to exercise its power throughout the entirety of Somalia. The insistence on the territorial integrity of Somalia coming from the West as well as strongly from the African Union ensures that very little official attention is paid to the state formation process in Somaliland. It therefore remains conspicuously absent from much of the state-building policy, practice and literature.

The insistence on an externally-led project of creating a central democratic state in Somalia reflects the current development trend of promulgating a universally applied style of state. Indeed, state-building in Somalia, as the first post-Cold War state- building project informed by the idealistic New World Order, marked the start of the promotion of an idealised modern democratic state through state-building and development projects. With a flux of new Eastern European states creating increased competition for investment and development assistance from the West, the message portrayed to African states seeking support regarding what was needed to obtain support became clear. As Dowden recollects: Europe and America gave African governments three conditions for their continued, if diminishing support: pursue free market policies, as laid down in the Washington consensus, respect human rights, and hold democratic elections – by which they meant multi-party democracy.

This emphasis on conforming to the dominant international norms informs state- building projects that began with the project in Somalia in 1993 as well as development and reform policies.4 The response to what are seen as financial, political social and security concerns or problems is a prescribed ‗one size fits all‘ approach5 to modern idealised statehood in order to create stability in not only the state in question, but also the international system of states. This ‗ideal‘ state conforms to liberal notions of acceptable statehood, exhibiting not only a democratic government and a secure territory, but also exercising good governance, providing public and political goods to the population, engaging in the international economy through liberal policies and eager for political interactions with other states and international institutions. In other words, the ‗ideal‘ state is one in which political, economic and security threats are eliminated and the practices, policies and structures of the state are familiar and easily accessible to the international community, particularly the West. The ideal state, therefore, is an extension of liberal intervention and as such subject to the control or subjugation of powerful states and international institutions. It does not reflect an already existing state structure, but rather comprises a wish list of sorts; it is a composition of factors that together would make the perfect acceptable or successful state not only for security, but also for political and economic relationships with powerful actors in the international community. The promulgation of the ideal state is more a liberal tool than an achievable reality.

Although the ideal state is a reflection of desires rather than a recreation of an existing state structure, this rubric of statehood is exhibited in policy as the desired outcome of interventionist actions. It extends far beyond active development or state-building policy, however. The dominance of this style of state in the normative liberal framework guiding international relations also creates an environment in which alternatives to or deviations from this blueprint of statehood and the path through which to reach it are not trusted, regardless of any success that may be exhibited. As such, international norms of what it means to be a state also direct domestic policy within developing states and, in particular, unrecognised states. For the latter, conforming to these acceptable standards of statehood is considered vital to achieving international recognition. By exploring conceptions of the acceptable or ideal state it is possible to understand, and also critique, the expectations for modern state formation. An ideal case study for this is Somaliland. For all pretences, Somaliland is a separate entity from its southern neighbour, Somalia, and is often referred to as the model of state formation in Africa: on empirical grounds it ―fulfils the principle criteria for statehood‖ and ticks the boxes of what a stable, modern state should be.

By all pretences it is a state, albeit one that lacks international recognition of sovereignty. A 2005 report commissioned by the World Bank, however, unveils a perceived problem with the state in Somaliland: a deviation from the liberal blueprint in the inclusion of traditional authority in the de facto state‘s central government.

The stated goal of creating a modern state is the same in both Somalia and Somaliland, but Somaliland has taken a drastically different path to achieving this and has set about creating a state on its own. Its exclusion from international involvement in the state formation process, however, has meant that the territory has been subjected to little direct interference from the international community. This isolation has allowed for Somaliland to create its own path to statehood and to define its own conditions for the introduction of demands for modern statehood, including democracy, in the governing structure and practices of the territory. The formation of the state in Somaliland reflects not only the normative dominance of the idealised acceptable or successful modern statehood, but also adapts these demands to Somaliland society. What is being created is a hybrid state that is inclusive of both familiar traditional governance structures as well as the newly introduced modern democratic government.

The hybrid government in Somaliland was integral to establishing peace and stability, but as the state continues to grow and develop this hybridity is being tested from within Somaliland itself. With domestic pressure for modernisation of government institutions, tensions between the ‗old‘ Somali style of governance and the ‗new‘ democratic government in the territory are becoming more apparent and problematic. This case study will examine state formation through the context of the normative framework of the ideal state. This thesis will consider the normative framework surrounding the creation of the ideal state and how this is enabled on a domestic level and in accordance with local political structures and priorities within the non- recognised state of Somaliland. This thesis will also examine the tensions between the ‗old‘ and the ‗new‘ resulting from this reconciliation between the two parallel governing structures. This introductory chapter provides an overview of research on the state formation process in Somaliland and its linkage to the wider discourse on the modern acceptable state. It will also briefly outline the key conceptual framework of the research, the chapter structure of the thesis and the methodological approach taken.

The Ideal Modern State and Indigenous Governance Structures

Within literature and policy on state failure, state-building and state development the successful or acceptable – the ideal – state is portrayed as one that complies with the normative framework of the modern state. As Berger notes, the growing body of literature concerned with failed and failing states ―attempts to facilitate the formulation of policies that will reverse this trend and create a world order of stable, economically dynamic and secure nation-states.

This is also reflected by the technocratic Ghani and Lockhart in the subtitle of their book, Fixing Failed States: A Framework for Rebuilding a Fractured World.9 Failed, fragile, weak or collapsed states are seen as states in crisis and as such are threatening to the cohesiveness and stability of the international system of states. Because of this there is a perceived incompatibility of failed states and the international system of states, thereby forcing the system to seek a way to strengthen its weaker chains. As Weiner indicates, weak, failed or fragile states create the threat of a bad neighbourhood, with the problems of one state quickly spreading to impact upon the others in its proximity. In line with this, failed, weak, fragile or collapsed states can be seen as crudely akin to a crack house in a residential neighbourhood: the malignant force of a failed state threatens the stability of a surrounding area and therefore must be addressed.10 Since removal of the entity is unfathomable under current rules of the international system, the response is a prescriptive remedy similar to an urban regeneration scheme that would be established to address a problematic neighbourhood. Berger associates this increased prescriptive attention with an emerging crisis of the nation-state system, with states failing to meet the rigorous demands of modern statehood threatening the stability of a system built on and dependent upon the functioning or legitimate sovereign states. However, the current means of addressing these problems itself are problematic in that the impending crisis is not one which can be addressed by ―technocratic prescriptions for the creation or stabilisation of particular collapsing or failing nation-states or the rehabilitation of the nation-state,‖ but rather the international community must reconsider the dictate of what is acceptable in the modern state.

As models of development have largely been dictated by the dominant discourses of the period, policies such as the push for political reform based on democracy‘s third wav, the economic sector oriented Washington Consensus and increased awareness of and concern for social and human security within sovereign states have significantly informed today‘s development policy and therefore the normative framework for acceptable statehood.12 Modernisation of state institutions and practices is integral to this framework; ‗backwards‘ traditional, indigenous or non-democratic structures and procedures are not efficient or effective in meeting the ideals being presented. Thus, modernisation of political and economic structures through democratisation, good governance practices and liberal economics becomes a vital component of the state. Even though an definitive statement of ideal statehood does not exist, policies such as Structural Adjustment Programmes and aid conditionality, together with the promotion of good governance and modernisation of institutions and government support the perception of an ideal, preferred, or acceptable state. In other words, within this literature and policy there exists a notion of the type of state that is preferred by the international community; a type of state that viewed as secure and stable and is preferable to engage with on an investment, development or financial assistance level. In addition to a liberal economy and democracy, the ideal state exhibited within this discourse is one that provides what Jackson terms empirical statehood and what Rotberg identifies as public and political goods. Amongst these are key components of Weberian statehood such as security, but also more socially orientated provisions such as education and health care, the maintenance of physical infrastructure and respect for human rights.13 Whilst there are no specifically stated parameters for this state, the popular characteristics defined by developed states and presented in literature and policy create a picture of the ideal that developing states should strive to become and what the international community should build through state-building interventions.

For those entities aspiring to legally recognised statehood, however, creating the ideal state can become more than just conforming to a normative model of statehood; it can become the perceived path to recognition and therefore to the political, social and economic interactions and benefits that accompany legal statehood. In reference to the enlargement of the European Union, Ghani and Lockhart paint a picture of a structured path for aspiring member states, with the accession to the EU being the end reward for following the pre-determined rules and regulations for membership.14 In a similar manner, the benefits of recognised statehood are the carrot being dangled in front of those territories wanting to be states. In the context of what Jean-François Bayart identifies as a strategy of extraversion,15 or actively seeking external sources of financial benefit, creating the ideal state with the aim of gaining recognition of statehood can become a means through which a territorial entity can benefit from interaction with the international community; the state becomes a strategic tool.

Through the medium of legally recognised statehood, ‗de facto‘ states endeavour to gain access to those areas largely reserved for states, such as legal financial frameworks and developmental assistance through international organisations. The process of creating an ideal modern state, therefore, can be a means to a financially, politically and socially beneficial end.

The concern here, however, is the uniform approach to creating stable or successful states using the blueprinted framework of the ideal state, particularly within non-Western or traditional societies. How are local structures and dynamics

accommodated in the creation or formation of a state, particularly within territories or entities with little or no experience of the modern or democratic state? The model of modern acceptable or successful statehood discounts the centralisation of indigenous or traditional governance structures, particularly in Africa, as they are believed to be backwards, corrupt, unpredictable or unstable. Although indigenous structures are viewed as useful when engaging locally in governance or development projects, their exclusion from the central state creates a situation in which the expectation is the creation of a modern and acceptable state in varied social or political contexts. As a result, modes of social and political organisation that are specifically tailored to the territory and society, yet do not follow the Western model of statehood, are often the target of reform by external donors and institutions as those unfamiliar alternatives do not conform to the ideal and trusted picture of the successful state.

Somaliland is such a case. Outwardly, the outcome of the state formation process in Somaliland appears to be a modern democratic state – albeit an unrecognised one – and the modern practices of the state are widely referred to in Somaliland‘s quest for international recognition of sovereignty. The imposition of modern democracy within the complexities of Somaliland‘s political and social environment was not as simple as just creating a democratic government and modern state practices, however, and was viewed as potentially destabilising by the founders of Somaliland. Because of this, a compromise was reached between clan governance and modern democracy, resulting in a deviation from the model of the modern state with the formation of a hybrid government in Somaliland. The government being formed is thus a product of reconciliation between ‗old‘ traditional structures and the ‗new‘ democratic structures and practices, thereby creating a central government inclusive of and dependent upon both. This thesis will examine the creation of such a state, asking why a modern democratic state was created, why the traditional was included in this state, and how the complex relationship between the old and the new functions in the formation, the growth and the future of the state. This thesis will also consider what the implications of the success this hybrid government are for not only for Somaliland, but for the broader picture in the context of the discourses on state formation and state-building.

Situating Somaliland

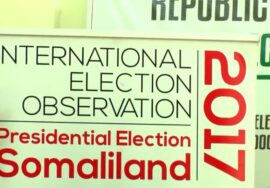

Somaliland proves an interesting case in that what is occurring in the territory is state formation that whilst informed and guided by international norms and standards of statehood, is also proceeding as an indigenous process with minimal direct external intervention. In contrast to the fraught filled long-term international state-building project taking place in Somalia, Somaliland is an oasis of calm in the chaos of the archetypal failed state. Although Somaliland appears to conform to the standards and requirements of acceptable statehood, despte its declaration of independence in 1991 it is not recognised as an entity separate from Somalia. Because of its inability to access international structures and institutions that are reserved for sovereign states, achieving recognition of statehood has become a primary goal of the government in the territory, with the creation of a democratic state at the centre of Somaliland‘s strategy. Whilst on the surface the state does exhibit the characteristics of a successful modern state and the government engages in an aggressive international public relations campaign advertising and espousing its success, it does deviate from the ideal statehood mould in that it has incorporated traditional Somali forms of governance in the central state structure in the form of a house of parliament. Whilst there is no conspiracy to hide the traditional nature of this body, its promotion as a primarily legislative body downplays those functions of the institution that are associated with the indigenous clan governance structure.16 With the objective of obtaining recognition of sovereignty in order to be capable of fully participating in the international system of states, and with the structure and function of the state apparatus appearing to conform to the acceptable state framework, the question must be raised of why a traditional institution was included in the government of this aspiring state? Indeed, without the inclusion of this traditional element from the beginning of the state formation process, the territory would not exhibit the level of peace and stability that exists today; and without peace and stability the introduction of a modern, yet foreign, democratic governing structure would have encountered significant difficulties. Whilst the inclusion of the traditional was essential to the initial stages of state formation, however, its continuance in the growing and evolving central government has begun to be questioned by elements within the Somaliland government and society. In order to maintain the uniquely Somaliland structure that has ensured stability, re-negotiating the relationship between the old Somali governance system and the new democratic structures and practices in the hybrid government is the focus of the next phase of state formation in the territory.

For purposes here it is important to distinguish between state-building and state formation projects. The term state-building is predominately used in reference to externally propelled and controlled re-building or re-creation of state institutions in legally recognised and sovereign states. State-building projects are generally based on the pre-existence of a state apparatus in some form; in literature and practice, state- building typically refers to the re-building of a collapsed, failed or post-conflict state or a previously autonomous territory within that state.17 State formation, on the other hand, is not commonly referenced in association with contemporary states. Rather, it is most often used in association with the creation of European states.18 It is the emergence or creation, rather than the re-building or even imposition, of a new state. State formation is the process in which a new state, including its governing apparatus, is domestically created rather than the externally-led restructuring of a pre-existing state structure; it is generally an indigenous process that is starting from scratch or close to it. State formation does not discount the pre-existence of a nation or a sense of nationality, but rather is primarily concerned with the more legal, technical and structural aspect of obtaining recognised sovereignty, as well as creating the governing structure that maintains the Weberian condition of monopoly of force and the modern demands good governance such as social provision and responsibility. State formation, therefore, is creating a new state entity from within rather than externally re-building a pre-existing state. Put simply, state-building is an externally led project aimed at rebuilding state structures and strengthening state functions, whereas state formation is predominantly an internally devised process aimed at creating new structures and functions. Whilst what is taking place in Somalia is an international project of state-building, what is taking place in the northwest territory of Somaliland is an example of state formation.

With the ideal democratic state being the end goal in state-building and development projects, as well as modern state formation projects, a set of guidelines for statehood and a blueprint of the ‗good‘ or ‗strong‘ state have been put forward. Whilst Somaliland follows this to an extent in that what is being created in the territory is a democratic state exhibiting many desired attributes of acceptable governance, the divergence in the inclusion of indigenous or traditional rule in the government sets Somaliland apart. This inclusion still puts Somaliland on the path towards democracy, but it does so in a way not defined by the international community but rather by Somaliland itself. The state being created in the territory is one that makes democracy work by tailoring the ideal to fit and therefore be possible in Somaliland. Because of the deviation, however, the success of the Somaliland challenges the dominant acceptance of the acceptable modern state. In balancing a desire for recognition of sovereign statehood with the need to create a stable governing structure in Somaliland, the shapers of this government have also created an interesting case of state formation for study. The case of Somaliland raises interesting questions concerning not only dominant state-building and state formation discourse, policy and practice, but also questions the ‗cookie cutter‘ approach commonly found in both literature and policy.

With that said, it should be noted that whilst the approach to state formation taken by Somaliland has been successful, it is not the intention of this thesis to suggest that the territory‘s distinctive experience should be carbon copied by other territories or states. What has worked for Somaliland is a tailored fit. Its importance is not that it has created a new blueprint for non-Western state formation or state-building, but that what has been created works for Somaliland and has been successful in creating a strengthening stable state within the remnants of chaotic Somalia. Somaliland is an example of how the model of acceptable statehood fails to acknowledge the importance of local social and political dynamics in contributing to the stability and success of a developing, re-building or forming state. It is because of this that the examination of the government in Somaliland in this thesis focuses on the deviation that has proved to be the foundation for stability in the forming state: the inclusion of the indigenous traditional governance structures into the Somaliland government. It must also be noted that it is not the purpose of this thesis to assess Somaliland through the discourse of right to self-determination. The complexity surrounding the international community‘s response to and policy regarding Somaliland‘s declaration of independence is best saved for a separate project. However, it would be misleading to present the assumption that the inclusion of traditional authority in Somaliland‘s government is the sole reason for lack of recognition. Whilst the power of the clan authority in the government has been noted as a concern, issues regarding Somaliland‘s placement within Somalia and expressed policy protecting territorial integrity in the region are also considerable obstacles to recognition. Until Somalia is stabilised, Somaliland is unlikely to be recognised. The isolation due to this, however, has been beneficial to Somaliland as the territory has been granted the time and space to ―go it alone.

Overall, examining Somaliland‘s state formation experience is valuable on many levels. The territory provides an excellent platform for the study of contemporary state formation, particularly how this is shaped or reactive to normative values of statehood. The territory also proves interesting in examining the interaction between Western ideals and traditional practices and structures. Somaliland is relatively untouched by either researcher or practitioner, making its virtual isolation an interesting test tube in which the indigenously created state and its strategies for recognition, its interaction with the modern acceptable state and its adaptation of the ideal can be studied.

Chapter 2: State Failure, State Formation and State Utilisation

States have historically derived from various specific and by no means universally realised conditions, and the global political system has until recent times comprised areas under the control of states, areas regulated by other forms of governance, and areas with no stable government at all.

The rise and fall of states is nothing new. From the time of Westphalia and European absolutism, states have come and gone in the historical processes of state formation,

The modern Western state has taken centuries to reach what is exhibited today, with a Darwinistic survival of the fittest approach contributing to the evolution of the membership of the international community of states: the modern Western state is the product of a lengthy process rather than a unitary declaration or act. United Nations Plenary Session 864 (1960) and Resolution 2621 (1970), however, altered the exclusive club of statehood and as a result the number of states in the international system increased drastically.The bestowing of sovereignty and therefore statehood upon the former colonial territories, the majority of which are located in Africa, thrust these new non-Western states into the international system as fully sovereign states on par with those states that have existed for centuries. Herbst notes the obvious in recognising that state formation and consolidation in post- Westphalian Europe differs greatly from state formation and consolidation in as within Africa the creation of independent states was superseded by decolonisation and the granting of blanket sovereignty. As a result, what took place within the majority of former colonial territories was not state formation but rather state bestowing that took for granted the existence of state structures and practices. All of this together makes obvious one of the most fundamental yet most erroneous normative assumptions of policy and research surrounding state formation and failure: that all states will reflect or even follow the ‗European path.‘ The above-mentioned resolutions highlight the key distinction between European state formation following Westphalia and recent state formation in former colonies: the blanket sovereignty granted by the international community – through the UN – following decolonisation bestowed juridical sovereignty upon the new states regardless of the existence, or lack thereof, of what are widely identified as ‗functioning‘ or ‗acceptable‘ state structures and practices. As Jackson states, ―[t]o be a sovereign state today one needs only to have been a formal colony yesterday. All other considerations are irrelevant.Whilst empirical statehood was not an explicit concern in the granting of statehood following decolonisation, the opposite is apparent today. Current development policy centres on good governance, or what it means to be a legitimate, competent and accountable state, as vital to development and growth. This is nowhere more apparent than in the 2002 Monterrey Convention, which asserts:

[g]ood governance is essential for sustainable development. Sound economic policies, solid democratic institutions responsive to the needs of the people and improved infrastructure are the basis for sustained economic growth, poverty eradication and employment creation. Freedom, peace and security, domestic stability, respect for human rights, including the right to development, and the rule of law, gender equality, market-oriented policies, and an overall commitment to just and democratic societies are also essential and mutually reinforcing.

Carothers also notes this emphasis on governance in his work on democracy, stating: [i]n reaction to accumulated frustration with the negative developmental consequences of unaccountable, unrepresentative governments in many countries,

the development community embraced the idea that good governance is necessary for development. laden terminology often used in discussions on good governance, such as ‗sound,‘ ‗unaccountable,‘ ‗acceptable,‘ ‗legitimate‘ and ‗competent,‘ denote not only an act of assessment, but also a sense of superiority and judgment – in this case in reference to the developed world towards the developing. These assessments and judgements are apparent nowhere more strongly than in literature and policy regarding what have been termed ‗failed‘ states. Assessing of the effectiveness of states, specifically those within the ‗developing world,‘ and the degree of ‗goodness‘ in the governance of those states evidences the dominance of what Jackson distinguishes as empirical statehood in modern conceptions of what it means to be a state.8 This is not only a sharp departure from the Westphalian statehood applied to the early European states, but also from what was required for statehood in the immediate post-colonial era.

To understand modern state formation, one must first understand the evolution of the conception of the state from juridical conditions derived from Westphalia, through to the empirical pre-eminence found in modern normative values surrounding statehood. This chapter will examine this development as a pre-cursor to a critique of the discourse on failed states. In the context of the assessment of functionality or empirical attributes deemed necessary to be an acceptable or stable state, this chapter will conclude by offering a critique of this value-laden assessment and offering an alternative framework through which to identify and understand non-Western political organisation and practices, particularly within the African state. In separating the non- Western from its Western counterpart, it is possible to examine political organisation and function without assessing its effectiveness or legitimacy against normative Western political practices and state composition.

From Westphalia to Governance

The 1648 Peace of Westphalia is widely accepted as the landmark agreement that laid the foundation for the creation of independent demarcated sovereign states as well as the beginnings of the interstate system. As populations within Europe increased and land became more valuable both economically and politically, sovereigns and other powerful actors began competing for territory. The creation of states within Europe through the establishment of absolutist sovereignty was a means through which the territory of a sovereign could be protected against invasion or usurpation, particularly in border regions. Control of territory and a monopolisation of force necessary to extract rents and taxes was considered vital to the growth and sustainability of the state.9 This concern over clear territorial demarcation and security rather than the provision of social goods as the definitive tenet of sovereignty and therefore statehood was, as indicated primarily by Max Weber,10 a necessary precursor to the formation of the state apparatus itself. The Westphalian state, therefore, favoured territorial security and to a lesser extent, economic security, over humanitarian and social welfare provided by the sovereign. The ability to control a territory and to accumulate the capital necessary to ensure and maintain the territorial integrity of the state was the foundation of early statehood.

Drawing on this Westphalian sovereign guarantee of territorial boundaries, Max Weber offers a concise and widely used conception of the state. Weber asserts that a state is a corporate or bureaucratic group that has compulsory jurisdiction, exercises continuous organization, and most importantly, claims a monopoly of force over a territory and its population, including ―all action taking place in the area of its jurisdiction.‖11 Within this, Weber augments the rudimentary Westphalian conception of the state through acknowledging the empirical actions of the state in addition to the existence of a legal territory. Although under this definition his concern with the empirical maintains the focus on state actions in maintaining security and control within the state as well as the territorial integrity of the legal boundaries, the empirical is inseparably related to the juridical. It was not until his later works – those specifically in response to German political occurrences of the time – that he delved further into an assessment and proposal of the ideal empirical attributes of a state.

Consistently for Weber, if the monopoly of force by the national government is absent, the territory exists in a realm of statelessness. Whilst social, humanitarian, economic and political responsibilities may be interpretively derived from this definition through an examination of the elements of control or organisation, whether charismatic leadership, traditional leadership, or bureaucratic control,12 engrained in this definition is the persistent emphasis placed on force necessary to first achieve and then maintain statehood.

From Juridical to Empirical

Whilst territorial control and monopoly of force within a territory invariably remain essential components of modern statehood, the evolution of what it means to be a state has resulted in increased importance being placed on the actions of the central government outside of the realm of physical or territorial security. As stated previously, Weber expanded upon his definition of the state in response to pre-World War I German politics. Regardless of the German-specific nature of his commentary on the state, it, together with his earlier ruminations, continues to shed light on what Weber believed a state should be: physical security and monopolisation of force remain the primary responsibilities, but the state also should not have free reign in regard to how it treats the population. Due to the specific nature of Weber‘s conception, however, it is difficult to apply it broadly as his Eurocentrism cannot be ignored. Going further in offering a more contemporarily relevant definition, Ian Brownlie incorporates the criteria for statehood codified in the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States in his conception of the state. He describes the state as a legal entity – recognised by international law – with four main elements: a defined territory; a permanent population; an effective government; and

independence, or the right to enter into relations with other states.13 Compared with Weber‘s primarily security centred conception of a state, and with the criteria espoused in the Montevideo Convention, Brownlie deviates in that although he recognises the importance of territorial security, he also places emphasis on the internal occurrences and practices of the sovereign within the element of ―effective‖ government. In a similar theme, Robert Jackson, in his presentation of what he terms quasi-states, articulates that modern states exhibit two forms of statehood: empirical and juridical. Juridical statehood is the internationally recognised sovereignty over a legally delineated territory. Following admission to the United Nations, ex-colonial states, as Jackson argues, ―have been internationally enfranchised and possess the same external rights and responsibilities as all other sovereign states: juridical

statehood. The key identifier for juridical statehood, in this sense, is the granting of the rights and responsibilities of statehood by the international community (in this case, the United Nations) as purely international or external responsibilities based on the existence of legally recognised boundaries. Internal responsibilities are not a component of juridical statehood.

According to Jackson, purely juridical statehood is incomplete statehood. He argues that the modern state must also possess and exhibit empirical statehood, or internal responsibilities. He argues that empirical statehood undoubtedly began with the earliest modern states in Europe, although still in a force-centric manner. Echoing Weber, Jackson affirms that these states, consisted in a populated territory under a ruler who claimed the territory as his realm and the population as his subjects and was able to enforce the claim. He possessed a government apparatus that could project royal power and prerogative both internally and externally.

Although the existence of monopoly of violence continues to dominate, according to Jackson sovereignty in its historic sense was not only respected externally, but was exercised internally. A state was not complete, to use Jackson‘s terminology, if it did not present both external as well as internal sovereignty.

Just as the conception and understanding of the state has changed, it can be argued that the conception of empirical statehood has also evolved.16 When discussing empirical attributes of early mostly European states, Jackson excludes mention of state responsibilities to the populace. His discussion of the inclusion of the responsibility to the people occurs not in a positive manner, but instead becomes a concern when considering the new wave of statehood that occurred following decolonisation. In this granting of ―blanket sovereignty,‖ the empirical was overlooked in the rush to grant juridical statehood. Accordingly:

many [ex-colonial states] have not yet been authorized and empowered domestically and consequently lack the institutional features of sovereign states … They disclose limited empirical statehood: their populations do not enjoy many of the advantages traditionally associated with independent statehood. Their governments are often deficient in the political will, institutional authority, and organized power to protect human rights or provide socioeconomic welfare.

From this, Jackson makes a key distinction between complete and incomplete, or ‗quasi,‘ states in how the two types of states exercise external (over the territory) sovereignty and internal (within the territory) sovereignty.18 To clarify, for Jackson external sovereignty refers to territorial sovereignty and the state‘s ability to engage with the international system as a sovereign entity. Internal, on the other hand, refers to what happens within the boundaries of the state; it is the state‘s ability to effectively exercise authority over the population with the territory. Internal sovereignty, therefore, includes components such as style of governance, the state‘s social provision or treatment of the population, physical and infrastructural development and domestic economic policy. For Jackson, quasi states are those that exercise predominately juridical, or external, sovereignty within which ―sovereignty is a legal fiction not matched by an actual political capacity.‖19 Grounded in the conception of the liberal state, complete states, conversely, are those that have been granted sovereign recognition and that also exhibit what is deemed the beneficial internal workings of a state. Within his discussion of quasi states, therefore, Jackson places conditionality for complete, or acceptable, statehood on the existence of not only exercising the force necessary to maintain the sovereign borders, but also for the state‘s domestic responsibilities to the populace.

Rotberg further expounds upon this emphasis on state provisions in maintaining that modern states are responsible for mediating the ―constraints and challenges of the international arena‖ with the ―dynamism of their own internal economic, political, and social realities.‖ He also identifies the importance of physical territorial security to the existence of sovereign statehood. However, he places security at the top of a list of goods that a state must provide, indicating the importance of security but also noting that it is not the sole purpose for the existence of a state:

[n]ation-states exist to provide a decentralized method of delivering political (public) goods to persons living within designated parameters (borders) … modern states focus and answer the concerns and demands of citizenries … [political goods] encompass indigenous expectations, conceivably obligations, inform the local political culture, and together give content to the social contract between ruler and ruled that is at the core of regime/government and citizenry interactions.

Rotberg stresses that the provision of political goods is vital to the domestic legitimacy of the state, and as such in assessing the empirical performance of a state key political goods are hierarchically identified as valid tools of judgment and evaluation. Within this security is the top priority for successful states, and although Rotberg does not distinguish between physical and human security, based on the remainder of his list it can be assumed that physical security is the primary concern for a successful state. In addition to this, however, other more social-political goods are also ranked as being fundamental to a state‘s legitimacy and success, such as enforceable rule of law, free and fair participation in the political process, the provision of social goods such as health care and education, physical and economic infrastructure, communications infrastructure, environmental protection, sound and logical fiscal policy and even the promotion of civil society.

Under these assessments, states are not complete, functioning or legitimate if they are lacking in the empirical provision of public goods that are perceived as essential to effective rule within the legally recognised territorial boundaries of juridical states. Successful states, therefore, perform in a way that legitimises governmental rule domestically and internationally by protecting the interests and security of not only the sovereign and the territory, but the population as well. It is for this reason that much of the current development focus of the international community, particularly those areas concerned with fragile states or states on the brink of failure, is closing the gap between juridical and empirical statehood.

What is not recognised within mainstream literature and policy, however, is how the empirical evolved in Western states. Western states exhibit vast bureaucratic structures to ensure the well-being of the population. Ministries or departments such as those for education, health, transportation, and social welfare exist within the structure of the state in order to monitor or support the population, creating welfare agencies that exist in parallel to the more Weberian bureaucracies responsible for the physical security of the state. As a result, there is little gap between juridical and empirical. Within those states that are the target of academic scrutiny or development policy, however, there is an assumption that welfare bureaucracies and empirical institutions are either not needed or are already in existence in some sub-state capacity. Within African states, or other states considered to have strong traditionally based societies, for example, there is an unwritten assumption that society is self- reproducing through reliance on traditional structures, meaning central bureaucratic government ministries tasked with social welfare are viewed as redundant or inefficient as the more socially entrenched traditional support structures provide the necessary empirical goods. This is evident in contemporary development policies, particularly those of NGOs, where local indigenous institutions or structures are seen as more effective in social provision than the state and are thus placed at the centre of the distribution or enactment of development assistance.23 If the state, therefore, does not have the primary responsibility over the protection and support of society, what then is the purpose of the state other than to ensure territorial security? If the state is redundant in the area of social provision, what empirical attributes of the central government itself are necessary for the state to be ‗successful‘ and why the firm insistence within literature and policy on closing the gap between the empirical and juridical? Whilst these questions are impossible to answer, it remains important to continue to question the contradictions and the gaps within the normative and uniform expectations for ‗successful‘ statehood.

From Ideology to Action

The importance of the distinction between external and internal sovereignty becomes apparent when comparing international intervention in developing states during the Cold War to post-Cold War involvement. The relationship between the ‗Third World‘ and the West during the Cold War was one of ideological balance – assistance was given to leaders of the developing world and in exchange those leaders would join the ‗democratic‘ or anti-communist side in the ideological struggle. The Cold War patronage system ensured monetary and military support in exchange for ideological conditions; little regard was paid to occurrences inside the state apart from the appearance of ideological conformity and protection of borders. Thus, during the Cold War importance was placed on maintaining territorial boundaries, military capabilities and ideological leanings rather than the inner workings of the state and the relationship between the state apparatus and the populace.

Following the end of the Cold War and thus the patronage system, international focus moved away from the ideological leanings and the militarization of the state. As evidenced in President George H.W. Bush‘s short-lived New World Order, and later prevalent in the output and actions of the United Nations, in particular Boutros Boutros-Ghali‘s 1992 An Agenda for Peace as well as the advent of humanitarian intervention, the empirical actions of state leadership in regards to the treatment and

conditions of the populace became predominant over the state‘s juridical sovereign right to non-intervention.24 What is important to note, however, is that the current focus on state performance and empirical statehood identifies an expanded conception of statehood rather than a sudden change in the nature of the state itself. As Jessop notes, the notion of what it means to be a state is a perpetually incomplete and

Although Jessop discusses the changing nature of the state as a result of changing economic practice, the observation can also be applied to changes resulting from normative values determining what it means to be a state. In other words, what has changed is not the state, per se, but rather the conception or understanding of the state. Whilst provision of public goods and empirical statehood are not new concepts in relation to the state, the focus is no longer solely on the physical attributes of statehood but rather on the more empirical domestic occurrences. The conception of expected state action, both externally and domestically, has shifted from a focus on force to a focus on provision, both to the international community and the domestic population of the state in question. It is within this realm where the legal state separates from the normative state. Where Weber and Brownlie emphasise the legalistic monopolisation of force – a close derivative of the Westphalian state – contemporary conceptions of effective statehood have come to include the state‘s ability to provide for its citizens in the realm of territorial security as well as in terms of political, social, economic, and human security. Whilst the legal definition of sovereignty and statehood has changed little since the formation of the early European states, as evidenced not only by Weber‘s and Brownlie‘s definitions of statehood but also by the United Nations Resolution 864, the normative conception of statehood has evolved. This is increasingly evident within the discourse on failed and fragile states and what it means to be a state in today‘s international system.

Failed States, or Failed Ideals?

The assessment of state performance has reached a pinnacle with the recent attention on failed states. With the post-Cold War focus shifting from the ideological or military state to the humanitarian or governance state, the criteria through which to assess state performance have also altered. Whilst control of territory and therefore physical security remain of high importance in the assessment of state performance, social and humanitarian standards have become more prominent. These new benchmarks for statehood are clearly evidenced in literature concerning failed states.

Semantically, the term ‗failed state‘ is relatively new, although the concept of state failure is not. As Bøås and Jennings ascertain: [a]lthough the rhetorical and policy adoption of ‗failed states‘ is quite recent, intellectually speaking the concept has been around for a long time. Indeed,

‗failing‘ or ‗failed‘ are simply the most recent in a long list of modifiers that have been used to describe or attempt to explain why states residing outside of the geographical core of Western Europe and North America do not function as ‗we‘ think they are supposed to.

They continue in identifying previously used terms within scholarship, including ‗neopatrimonial,‘ ‗lame,‘ ‗weak,‘ ‗quasi,‘ and ‗premodern.‘27 Morton and Bilgin share this view of the place of the failed state in the international system in arguing that the failed state is nothing more than the latest representation of the problematic ―post-colonial‖ state. Whereas the term ‗failed state‘ was made popular by Madeleine

Albright during her tenure as United States Ambassador to the United Nations,29 after 11 September 2001 it became the dominant term associated with states in which there has been an ―implosion of government‖30 and where the absence of central authority creates a vacuum of sovereignty. Indeed, a commonly used definition identifies failed states as those in which ―the central government ceased to function and [is] unable to provide for the well-being of its population or protect it from internal or external threats. A failed state is unsuccessful at maintaining the most basic Weberian norms of statehood as well as in the areas of social provision and human security.

The Fund for Peace in its Failed States Index also considers economic conditions in its consideration of state failure, and the State Failure Task Force adds to these factors such as environmental protection and ―democracy level‖ as variables in its statistical determination of a failed state.

Although ‗failed state‘ is a popularly used term within academia and policy, definitional ambiguity exists surrounding what the phenomena actually is. Thürer, in his attempt to clarify the conception, offers the French language equivalent of etat sans gouvernement, or ‗state without government.‘ However, he also acknowledges that this term is too narrow, leading to a concept that overlooks the function of a state to instead focus on the presence of a state apparatus. He also argues, though, that the term failed state is too broad, encompassing ―the aggressive, arbitrary, tyrannical or totalitarian state‖ that would be considered failed ―according to the norms and standards of modern-day international law.‖ Identifying that neither term is―sufficiently precise,‖ Thürer chooses to use clarify his usage of ‗failed state‘ by stating that it should be understood as indicating a ―disintegrated‖ or ―collapsed‖ state,

thereby offering more definitional and conceptual vagueness in his attempt to solidify the term.34 To add to the confusion, the CIA commissioned State Failure Task Force identifies four different categories of state failure: revolutionary wars, ethnic wars, mass killings (genocide or ‗politicide‘) and adverse or disruptive regime change.35 The 2008 Failed States Index also reflects this extensive definition in that its taxonomical list identifies thirty-five states on ―alert‖ for collapse and failure, with another ninety- two in the ―warning‖ category. Only fifty out of 177 states on the list indicate sustainability or stability of the state, indicating that according to their criteria only a handful of the world‘s states are not failing or at risk of failing. Within these offerings a wide definitional expanse becomes clear, with everything from complete lack of government to poor governance to violent state actions falling into the broad conception of state failure.

Whilst recognising the imprecise definition of the concept, Derrick Brinkerhoff offers a useful elucidation into the meaning of state failure:

[i]n general, a failed state is characterised by: (a) breakdown of law and order where state institutions lose their monopoly on the legitimate use of force and are unable to protect their citizens, or those institutions are used to oppress and terrorise citizens; (b) weak or disintegrated capacity to respond to citizens‘ needs and desires, provide basic public services, assure citizens‘ welfare or support normal economic activity; (c) at the international level, lack of a credible entity that represents the state beyond its borders.

Whilst the emphasis on both territorial security and public goods is clear in this definition, exactly what constitutes state failure, how to assess failure, who assesses failure and whether or not there is an identified threshold that if crossed indicates failure remains uncertain. The exact meaning of the failure of a state is left open to interpretation and assessment, with the control against which a state is assessed being unspecified beyond vague specifications such as citizens‘ needs and desires and legitimate government. Following the arguments of Fiona Adamson as well as Martha Finnemore, it can be assumed that these standards for non-failure, or success, are based on the hegemonic ideals presented by the Western liberal state, thereby raising concerns of Eurocentric determinations, expectations and impositions on non-Western states. In other words, the broad conception of the ‗failed‘ state can be reduced to mean the opposite of the ‗functioning‘ Western state; the ‗failed‘ is the mirror image of the model of the ‗success‘ espoused in and propelled by the liberal state.

As Gros acknowledges, ―even the phenomenon – failed states – is poorly defined‖ as states that exhibit any degree of weakness or breakdown in terms of what is desired of state performance can be labelled failed. Confusion is exacerbated by the often synonymous use of failed with terms such as ‗collapsed,‘ ‗weak,‘ ‗fragile,‘ ‗quasi,‘ and even ‗rogue,‘ all of which have their own separate definitional ambiguity attached. What is consistent throughout the literature, however, is the prevalence of assessment and judgement based on conceptions of Western democratic statehood and the model or ideal state portrayed through normative assumptions. These value laden comparisons of success and dysfunction, particularly those that compose state performance taxonomies,41 paint a picture of superior versus inferior state forms, organisations and actions. The term – the classification, even – brings with it the semantically valued implication that ―[a] failed state[s] is a polity that is no longer able or willing to perform the fundamental tasks of a nation-state in the modern world.‖42 As a failed state is ―utterly incapable of sustaining itself as a member of the international community,‖ those considered to be as such ―subsist as a ghostly presence on the world map.

Yannis reflects on the synonymous use of ‗collapse‘ and ‗failure‘ in saying:

the term [failed state] can mislead if it is understood to imply a value judgement that there are specific standards of social, political and economic performance and success to which all states should aspire, rather than minimum standards of governance that reflect a universal consensus about the minimum requirements of effective and responsible government.

Although Yannis opts to use the ―more descriptive and dispassionate term ‗state collapse‘‖ throughout his work, the above statement highlights the value conceptions surrounding the term failed state; by highlighting the ambiguity it is possible to extract the underlying value assumptions of what a successful state should be. Yannis claims that normative minimum requirements of government should be the basis of performance evaluations, but he fails to clearly identify what these minimum standards are. One can only assume that Yannis is establishing his point of reference for state evaluation as the Western liberal democratic ideals of successful governance and statehood which are prominent throughout the literature on state failure. These value-laden assumptions of what an effective and responsible government should be contribute to a normative understanding, and framework, of what the expected performance of an acceptable or successful state is.

The emphasis on the ideals of successful statehood highlights an important distinction that is prevalent throughout current state failure literature: that of societal responsibility. Yannis, amongst others, makes clear there is an idealised point or standard of statehood at which to aspire that goes beyond the existence of a central government; a standard which incorporates Rotberg‘s political or public goods. It is here that the normative assumptions of what a state is expected to be become clearer: a central democratic government is expected to protect the territory and the people as well as provide certain goods and services. States that do not achieve this, therefore, have failed the standards of statehood, a departure from the more innocuous and literal etat sans gouvernement conception of the failed state. These standards of governance are echoed by Jackson, who claims failed states are those states that ―cannot or will not safeguard minimal civil conditions for their populations: domestic peace, law ad order, and good governance. During the Cold War and the liberation and nationalist struggles in the former colonies, when movements attempted to seize states and remake them in the name of the people the West intervened and armed the states in order to resist these popular pressures. Today, however, the opposite is taking place and the West is intervening to remake states in the name of the people in an attempt to ensure the security of the population. The intervention taking place carries the semantics of modernising and developing, and what is being created is a human security or governance state (see Chapter 3). The implication of failure to society as an aspect of state failure not only displays the value placed on societal responsibilities of states to their populations, but also links the existence of an effective central government to societal stability. The association of the failure of the state with failure

to society deviates greatly from the Cold War assessments of state performance that placed emphasis on military control rather than societal security.

In the early post-Cold War years, state failure was perceived of as being problematic primarily because it was detrimental towards local populations and regional stability. Following 11 September 2001, however, state failure became a widely recognised international security threat. As such, state failure,

is now increasingly identified with the emergence within a disintegrated state of non-state actors who are hostile to the fundamental values and interests of the international society such as peace, stability, rule of law, freedom and democracy… [it is] the descent of a state into Hobbesian anarchy.

The importance placed on democracy and the expectation of this style of governing evident within the above statement again exposes normative standards of statehood.

Failed states are seen as a threat to democracy and therefore are presumably undemocratic and descending into Hobbesian anarchy. These dangerous states which, according to Rotberg, are ―black holes‖ where a ―dark energy‖ exists and where ―the forces of entropy have overwhelmed the radiance that hitherto provided some semblance of order,‖ are antithetic to secure liberal democratic states.47 Whereas this language may appear to be overdramatic, the sense of pessimism and even despair portrayed is typical of the posture found throughout literature on failed states.

Much of this pessimism derives from recognition of the lack of socially and economically focused political goods. Ayoob concedes that ―[w]hat are considered in the West to be norms of civilized state behaviour – including those pertaining to human rights of individuals and groups‖ are ignored or neglected in many states, particularly former colonial states, which are still establishing government structures. Excluded from much of the literature is an acknowledgement that many of those states considered to be failed are former colonial states with relatively new sovereign statehood. Of the thirty-five states identified as failed or failing by the 2008 Failed States Index, only four do not have a colonial past: North Korea, Ethiopia Liberia and Nepal. Amongst the remaining thirty-two, eighteen are found in Africa. All but two of the former colonial states identified as on alert of failure were created in the twentieth or twenty-first centuries, with the most recently independent being East Timor (2002), Uzbekistan (1991), and Zimbabwe (1980).49 As many of these states are new states, it must be acknowledged that they are continuing to undergo the lengthy and often violent process of state formation.50 In this context what is often identified as breakdown and decay of social order can also be viewed as the necessary steps of state formation and consolidation.

The criteria against which failed states are being judged, although often ambiguous or not concretely identified, are criteria established in the context of the Western liberal democratic state created through the lengthy formation of the European state. De jure sovereignty was granted by the United Nations following decolonisation on the assumption that political and economic stability and viability would ensue in the new states.52 What is omitted from much of the study and policy regarding failed states is that former colonial states were admitted into a system that had pre-existing and established norms and standards as to what statehood was; a marked difference from the fledgling system that existed during the time of the emergence and formation of the European state. Because of this, former colonial states must be expected to take a markedly different route towards statehood than European states. In the context of Africa:

Because of this assumption, much of the current literature on state failure focuses on characteristics of the process of failure, with particular attention paid to Iraq and Afghanistan as well as African states. Along with describing and identifying symptoms, but not causes, of state failure, prescriptive methods are put forth for which to pull these states out of their ―tense, deeply conflicted, dangerous‖55 environments in order to make them strong and viable members of the international community of states and reduce the threat they may pose to the rest of the world. That is, they must be ‗restored‘ to the Western-style state that most were granted at independence in order to sustain an effective or functioning future.

Failing the Norms of Statehood?

As Gourevitch critically observes, by viewing state failure as domestic anarchy, analysts and policymakers ―do not have to understand the local dynamics driving the crisis … Instead they can simply treat it as chaos. Implicit in this analysis is that by identifying state failure in Western terms – that is, applying the assessment of failure, chaos or anarchy to situations that do not comply with norms of statehood – the self- image of the ideal Western state is reinforced and intervention to ‗fix‘ or ‗remake‘ the chaotic state is justified. As a result, non-Western forms of political organisation and practice are often overlooked as legitimate forms of state organisation and are therefore excluded from state-building, political development or governance reform projects. Whether they be shadow networks headed by warlords or strongmen, or indigenous or traditional means of social, economic and political control, these forms of organisation can, and often do, provide a form of law and order within the territory or state. The focus of much of the literature on state failure is not on understanding what causes the perceived chaos, but rather proposes possibilities for international intervention into failed or failing states as a means of establishing a functioning government and to restore order, albeit often without taking into account these local sources of order. Within this is the underlying assumption that the key to a successful state, and the key to preventing state failure, is to create a modern democratic state that is familiar and understandable to the West, regardless of the effectiveness of pre- existing structures of control.

Whilst shadow networks are commonly associated with criminality, traditional or customary structures are also viewed negatively in the context of the liberal normative framework of statehood. In his explanation of the evolution of the state Weber defines traditional authority as legitimated by sacred traditions and considers it an important early step on the path to modern statehood.58 What is important to note, however, is that Weber does not endorse the inclusion of traditional authority in the end result of modern statehood but rather rejects legitimacy based on it as archaic or retarding progress. Indeed, Weber‘s conception of traditional legitimacy identifies it as ―the authority of the ‗eternal‘ yesterday; the perceptions of backwardness, regression and negatively being stuck in the past60 place traditional authorities in a position that is contrary to the creation of a modern ideal state. The attitude expressed by Weber is echoed in contemporary liberal policies aimed at state-building, reform and development.

Whilst rejecting the inclusion of traditional authority in central government, international institutions do often recognise benefits resulting from the utilisation of traditional structures in local projects. Institutions such as the World Bank view that ‗legitimate‘ traditional governance structures, as opposed to ‗illegitimate‘ structures such as those headed by warlords or strongmen, can play an important role in enabling development projects and governance reform within local communities by utilising pre-existing and well-known social, political and economic structures. However, as Garrigue notes, this does not come without conditions as there is a ―particular phase‖ in the evolution or strengthening of a state after which traditional structures can become useful. It is only when traditional structures ―become one among other stakeholders of the local governance‖ and are parallel to the state rather than a component of or a competitor to modern governance that they can be effective in implementing or enabling policies or reforms and therefore can be accepted within the scope of the project.61 In other words, it is only when traditional authorities become complicit in and therefore controllable through the project that they become useful. As such, the traditional authority becomes another level of complicit elite within the state. The recognition of the benefits of traditional authorities, however, rarely extends into the sphere of central government, particularly democratic government. As indicated, traditional authority and legitimacy derived from traditional structures in this realm are often perceived of as being backwards, unpredictable, unreliable and contrary to the practice of modern democracy and the existence of a modern state.

The stance of international institutions and development organisations in regards to the inclusion of traditional authority in a modern central government is indicative of the bias against centralised traditional governance. Ottaway and Mair argue that these actors ―seem to respect the essential rules of civilized behaviour,‖ but often do not have access to means of coercion and are therefore ineffective in maintaining the basic security requirements of a state.62 The Weberian emphasis on security is not the only concern, however. As the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNCAE) Traditional Governance Focus Group explains, traditional authorities are incompatible with the ideal of democratic government: in democracies ―rulers are not chosen by divine right or on the basis of a hereditary entitlement,‖ meaning that ―[o]ne of the difficulties for chieftaincy is its incompatibility with the democratic ideal‖ of recognises the predominant view of the relationship between modern democracy and traditional authorities in governance discourse and practice as being competing paradigms of governance at extreme opposite ends of the Shivakumar expands on this, stating that within liberal international policy there is a common perception that traditional authority simply cannot be trusted. Accordingly, although a traditional authority has the potential to be beneficial in an institutional or central capacity, as every component and historical aspect of that authority cannot be traced or identified the risky elements of the unknown and the unpredictable are too great. Shivakumar goes further, stating that as we have to ask whether the terms of competition among alternative problem-solving routines have been conditioned with respect to specific normative standards as reflected in the agreed on rules of the game,‖ there is no way of ensuring that the traditional authority in question is the optimal option.65 Therefore, in comparison with the ‗tried and tested‘ system of modern democracy and acceptable statehood, because the traditional institution cannot be traced through the ―sieve of time and trial…we cannot…expect the result of processes of institutional evolution to produce,

Whereas the unknown impacts only minimally on localised projects, and therefore the international community as a whole, the uncertainty surrounding an institutionalised version at the state level is perceived to be too great and therefore the risk should be excluded.

Critical of interventions, Milliken and Krause argue that strong and legitimate state institutions must have their roots in local populations and organisations; externally shaped institutions are not the best solution to the lawlessness and anarchy that is associated with state failure.67 Ottaway echoes this in saying that attention must be paid not to ―the creation of institutions but to ―generating power and authority. Chopra identifies the difference between a crisis due to the collapse and failure of government and a perceived crisis of legitimacy within a structurally sound, albeit non Western-style state structure in saying, ―there is a profound difference between anarchy defined as the absence of a national executive, legislature and judiciary, and the actual breakdown of indigenous social structures.‖69 To quote Gourevitch, ―[w]hat state failure discourse misses is that the central issue during political crises is a crisis of legitimacy. With little attention being paid to understanding the political structures and socio-economic-political environments in which failure takes place, unfamiliar non-Western state structures are often labelled as failures and prescriptive

methods of intervention are proposed in order to ‗cure‘ the dysfunctional. Milliken and Krause note:

one way to think about the contemporary anguish over state collapse is to note that what has collapsed is more the vision (or dream) of the progressive, developmental state that sustained generations of academics, activists and policy-makers, than any real existing state.

What has failed, therefore, are not solely a small number of individual states, but also the dreams of the proliferation of the ideal state that has not been realised.

Forms of political organisation that do not mimic or comply with the familiar Western state or the picture of an ideal modern state are often present in states identified as failed; it is often these forms that create the basis for and often provide the rule of law, monopoly of force and social provisions mandated by the acceptable state. However, they are often overlooked, ignored or not identified by academics and policymakers due to their unfamiliar nature or due to the presence of a multiplicity of actors exercising variable forms of non-centralised control over regions within the state‘s