Republic of Somaliland NDP III 2023-2027

Republic of Somaliland National Development Plan III 2023-2027

The Government of Somaliland has developed successive development plans to address its national development challenges. The National Development Plan (NDP III, 2023-2027) is a medium-term strategy designed to unlock the country’s potential in all sectors of the economy to achieve inclusive, sustainable development and poverty reduction. The NDP III builds on the achievements and lessons learned during the NDP II period (2017-2021), which concluded in December 2021, and aims to achieve the socio-economic transformation envisioned in the Somaliland National Vision 2030. During the NDP II period, the country grappled with external shocks and the persistent drought in the sub-region. The global shock of the COVID-19 pandemic taught Somaliland – and the entire world – the importance of building resilience in the economy, especially for the poor and vulnerable. As such, one of the notable updates to the NDP III is the addition of the Social Protection sector and climate change adaptation alternatives to strengthen the economy’s resilience to recurrent shocks. The NDP III envisages a diversified and resilient economy anchored on the principles of sustainable development. The plan prioritizes physical and human capital development as conduits to economic development. The NDP III will include significant investments to uplift infrastructure, mining and extractives, water facilities, and food security, and build on achievements in the health and education sectors. As in the past, the government’s investments in the overall governance architecture remain high, as no meaningful development can occur without democracy and the rule of law. The NDP III has many strategies to support economic development by improving the business environment for the active participation of domestic investors and attracting foreign direct investment. The plan will continue to emphasise easing the process for registering businesses through one-stop shops, enhancing financing conditions, improving energy access, and lowering costs to reduce the burden on businesses.

The NDP III outcomes and cost estimates are the aspirations of the various sectors and government institutions over the next five years.

The plan is meant to clarify the direction and structure of Somaliland’s national development, providing common ground for dialogue, facilitating the participation of a wide range of stakeholders and development partners, and promoting synergies to achieve shared goals. In this context, an essential precondition of successful implementation is “mutual alignment”. As the government is committed to aligning resources from the national budget with the NDP III, development partners are encouraged to follow suit based on international principles of development cooperation, as enshrined in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness.

As part of the NDP III implementation strategy, the government has initiated a National Development Fund (NDF) that is based on transparent and accountable governance principles to facilitate joint financing of priority interventions. The government will engage with development partners to build the NDF into a central financing mechanism for Somaliland’s long-term development.

The implementation of the NDP III will also involve the government engaging with its development partners and inviting them to jointly formulate National Flagship Programmes (NFPs) with clearly defined plans, budgets, implementation arrangements, and committed finances. These NFPs are designed to address the following priorities:

- Boosting Somaliland’s economic and private sector development and exploring and maximizing opportunities and multiplier

effects created by recent significant private sector investments.

- Improving the resilience and livelihoods of agro-pastoral and pastoral communities in areas most vulnerable to climate change and recurring droughts.

- Developing climate-smart infrastructure in partnership with local governments and the private sector to improve access to affordable services crucial for developing value chains and private sector initiatives, such as energy, water, roads, information and communications technology, and markets, among others.

- Broadening and accelerating support to the decentralisation process that was started with support from the UN Joint Programme on Local Governance (JPLG).

The government will commit sufficient resources to monitor the NDP III during its implementation. All ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs) are called upon to reinforce their internal capacity to continuously monitor progress through outcome targets and annual operational benchmarks. A separate NDP III Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning (MEAL) supplement provides technical guidance to MDA staff to harmonise monitoring and reporting efforts across government institutions. The learning from the mid- and end-term evaluations will offer vital recommendations for the formulation of Somaliland’s next Vision Paper. It is critical that monitoring and evaluation are conceived and implemented as joint exercises, leading to broad ownership of conclusions and recommendations

Finally, I want to reiterate the importance of alignment by all stakeholders in terms of objectives, choice of interventions, financial commitments, institutional and implementation arrangements, and monitoring and reporting on progress. I am confident that with the spirit of alignment, the NDP III will successfully improve the lives of my fellow citizens.

1.1 Introduction

In 1991, Somaliland had the enormous task of building a functional state after the devastating effects of the civil war that caused tremendous damage to the country. With determination, successive governments laid the foundations upon which to build future developments.

Thus, the country’s development evolved out of a process of more than twenty years of grassroots peacebuilding and state-building. Over this time, the Somaliland government started engaging a range of international partners, including the United Kingdom, Denmark, Germany, Norway, the Netherlands, the European Union, the World Bank, the African Development Bank, and a range of United Nations agencies and national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs/INGOs).

The first joint effort to work towards a common understanding of the priorities of Somaliland was the 2006 Joint Needs Assessment (JNA), leading to the 2007-2010 Reconstruction and Development Plan (RDP), conducted together with the United Nations and the World Bank.

These processes informed the thinking behind Somaliland’s first National Development Plan (NDP I, 2012-2016).

The then Ministry of National Planning and Development (MoPND) went on to develop the Somaliland Vision 2030. NDP I was written to operationalise the country’s vision and communicate with citizens and the diaspora.

At the start of NPD I, Somaliland was considered, by World Bank estimates, to be one of the poorest countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, with a per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of US$347. At the time, this was the fourth lowest in the world, ahead of Malawi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Burundi.

With perseverance and much needed reforms, including improved budgeting and planning of domestic resources, the National Development Plan II (2017-2021) achieved steady growth for the period, with GDP per capita increasing from US$557 to US$775. Compared to initial estimates in 2012, this is a jump from the fourth poorest country in the world to the eighteenth poorest in the world.

This steady growth has caused changes to the structure of the economy. Although still largely pastoralist and with livestock rearing a mainstay in the economy, other sectors have witnessed significant growth over the years. This is especially true of the service sectors, notably in retail trade, tourism (due to relative peace), and financial services, with remittances playing a catalytic role in the economy.

Leveraging the significant diaspora population, remittances continue to be the main flow of finance into the country together with development assistance. These serve as both a social safety net and key contributors to the growth in various sectors, especially in construction.

The re-emergence of the Berbera Port, with investments of US$440 million from Dubai Ports World, and its complementary infrastructure, the Berbera Corridor, is a testimony to the growing strategic role Somaliland could play in the Horn of Africa, reaping a peace and stability dividend. This is indicative of the improved investment climate in the country, with increased opportunities for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into other underdeveloped sectors such as fisheries and commercial agriculture. The oil exploration deal with Taiwan is another example of the improvements to and confidence in the business environment in Somaliland.

1.2 Demographics of Somaliland

The population of Somaliland was estimated to be 3.6 million in 2014 (47.9 percent male and 52.1 percent female) and projected to increase to 4.2 million in 2020, using a growth rate of 2.93 percent, with the bulk of the population living in urban centres.

The population of Somaliland has an average household size of six with 48 percent of the population being under the age 15 and roughly 72 percent of the population being under 30 years. Similarly, 48 percent of the population is within the working age group (15-64).

Somaliland’s population is young and has become more urbanised over time due to several factors, including repeated droughts. However, there is still a significant proportion of Somaliland’s population living outside of urban areas, whether living in rural settlements or as nomadic pastoralists. Urban, rural, and nomadic households differ significantly in terms of economic activities, sources of income, and consumption patterns, but also in terms of public service delivery challenges, such as the basic services of education, health, water, and sanitation. Although poverty is present across the country, those in non-urban areas are more deprived.

The different population groups stand at 53 percent urban dwellers, 11 percent residents in rural settlements, and 34 percent nomadic and agro-pastoral communities. Meanwhile, two percent of the population lives in settlements for Internally Displaced People (based on government and UN estimates). Having one of the highest fertility rates in the world, Somaliland has a broad-based age pyramid.

The population is demographically very young, with nearly two-thirds (61 percent) of Somaliland’s population aged less than 25 years and around three-quarters (74 percent) aged below 30 years.

Youth between 15-29 years of age constitute 26 percent of the population, while older persons (65 years and above) comprise only 6 percent of the total population. Nearly half (48 percent) of the population is within the working age (1564 years), highlighting the need to create jobs and ensure that training or education address the needs of the labour market. The sex and age distribution of the population is presented by the population pyramid in Figure 1.

The growing urban population is already reshaping the socio-economic dynamics in Somaliland. More individuals in cities mean an increased demand for services and jobs.

Also, this new trend is putting pressure on prices, particularly for food and housing. Somaliland’s economy is based on a dichotomous employment situation. Unemployment levels in urban Somaliland are exceptionally high – as much as 70 percent nationally.

On the one hand, there is an emerging service sector, which is generating increasing levels of quality jobs, but which are not adequately catered for by the local educational and training institutions. On the other hand, the bulk of the population is engaged in the traditional sectors of pastoralism, agro-pastoralism, artisan fisheries, and trade, which require minimum levels of education and are not expected in their present situation to lead to improved livelihoods. To the contrary, these sectors are coming under increased threats due to the consequences of climate change.

Diversifying the income sources of the population is a challenge that Somaliland must face. The creation of meaningful and adequate employment sources is a challenge every government must tackle.

Chapter 2 ACHIEVEMENTS TOWARDS VISION 2030 GOALS

2.1 Somaliland Vision 2030 and NDP III Structure Pillars and Sectors

In 2011, after 20 years of remarkable progress as an independent country, Somaliland decided to embark on the formulation of a vision that could encapsulate its long-term aspirations. The Somaliland National Vision 2030: A Stable, Democratic and Prosperous Country Where People Enjoy a High Quality of Life was developed, considering Somaliland’s past, present, and envisioned future.

Since its inception, the Somaliland National Vision 2030 has provided common goals concerning Somaliland’s future, enabling the country to take ownership of its development agenda. It also inspires the nation and its leadership to mobilise resources and overcome development challenges to attain higher standards of living. Moreover, the vision guides development partners to align their assistance with national priorities and aspirations. Importantly, it provides a framework upon which national strategies and implementation plans can be anchored.

The pillars upon which the Somaliland National Vision 2030 rests are i) Economic Development, ii) Infrastructure Development, iii) Good Governance, iv) Social Development, and v) Environmental Protection. Expanding upon the five pillars of the National Vision 2030 and the NDP II, and based on requests from the affected government institutions, the National Planning Commission (NPC) decided to introduce changes in the planning structure of NDP III.

Please note:

- The Judiciary Pillar was added to accommodate the courts. The Ministry of Justice remains in the Governance sector.

- The Social Protection sector was added to the Social Development pillar.

Underpinning and Cross-cutting Themes

As in the NDP II, the underpinning themes of Resilience and Human Rights are key and critical conceptual areas that provide the foundational basis for development that each sector rests upon. Cutting across each of the ten sectors are the following thematic areas:

- Displacement affected communities

- Gender

- Children’s rights

- HIV/AIDS

- People with disabilities

- Youth

2.2 Poverty and Inequality

Data on poverty and inequality dates back to the poverty report in 2013, done in collaboration with the World Bank.

The findings suggest that poverty is more prevalent in rural communities, where the poverty headcount stood at 37 percent. The urban areas were slightly better, with 29 percent of the urban population considered living in poverty.

It is important to mention that significant changes occurred between 2013 and the present, with the economy moving away from livestock dependency to be more service-oriented. The GDP per capita increased from an initial US$347 in 2013 to US$681 in 2022. This is likely to impact the population in different ways, ranging from economic activities to employment rates and household sources of income.

Based on the last labour force survey (2015), 50 percent of the population is in the labour force, but the poverty headcount ratio remains high among the economically active.

2.3 Social Development Education

As in many other countries, education is highly correlated with poverty in Somaliland, and it can be a route out of poverty. Household heads with higher education levels are less likely to be in poverty. Although adult literacy is close to the Sub-Saharan Africa average, Somaliland children are much less likely to attend primary school than children in other countries in the region.

Children who do not attend primary education are likely to grow up lacking basic cognitive skills. The lack of basic cognitive skills will reduce their productivity and wages as adults as well as reduce their ability to adapt to changes and shocks in their environment. Children in rural areas of Somaliland are much less likely to attend secondary school compared to those in urban areas, raising concerns about the disparities in education access between rural and urban Somaliland. Cognizant of its obligation under Article 6 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that every child has a right to education, the government of Somaliland has initiated various programmes over the period of NDP II. Despite the challenges, the Gross Enrolment Rate in primary education has improved only marginally from 29 percent in the 2018/19 academic year to 32 percent in 2020/21. However, the Gross Enrolment Rate in secondary education remained the same at 18 percent.

The Gender Parity Index at both primary and secondary levels decreased from 0.84 to 0.81 and 0.78 to 0.75, respectively. These are areas NDP III will strive to improve upon over the next five years. Educational attainment is higher for men than it is for women.

Overall, 21 percent of women have no education, compared to 17 percent of men. Approximately 50.9 percent of women and 42.9 percent of men in the households surveyed have not completed primary education. Ten percent of men attended secondary or higher schooling, compared to 9 percent of women.

Health

Although there are still considerable challenges in the health sector, noticeable progress has been registered in many health outcomes, as per the Health and Demographic Survey from 2020. Maternal mortality was reduced from 732 per 100,000 live births to 394 per 100,000 live births during the NDP II period. It is important to note in this context that the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel increased from 33 percent to 40 percent in the same period.

Between 2016 and 2021, the under-five mortality rate went down from 137 per 1,000 live births to 91, and the infant mortality dropped from 85 to 72 per 1000 live births. However, neonatal mortality went up slightly, from 40 to 42 per 1,000 live births. Breastfeeding is almost universal in Somaliland, with 94 percent of children born over the last two years being breastfed and the prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding in the first hour of birth is 69 percent.

Malnutrition improved marginally from 14 percent in 2016 to 13 percent in 2021. Also, in the context of communicable diseases, the incidence of new HIV infections per 1,000 uninfected people dropped from 6.8 to 0.03, while the incidence of tuberculosis dropped from 285 to 200 per 100,000 people and the incidence of hepatitis B dropped from 150 to 51 per 100,000 people.

Related to out-of-pocket expenditures, the Somaliland Health Demographic Survey (SLHDS) reports on households’ expenditures on health services based on the last month prior to the survey, showing that 27 percent of households spend less than $US50, whereas 28 percent

spend US$50-99, 18 percent spend US$100-199, 7 percent spend US$200-299, and 20 percent spend US$300 or more on healthcare.

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

According to the recent SLHDS, 41 percent of households get their drinking water from improved water sources. However, there is a slight discrepancy between the urban and rural population.

This data shows that less than half of the population has access to improved drinking water sources, defined as piped water on premises and other drinking water sources, like public taps or standpipes, tube wells or boreholes, protected dug wells, protected springs, and rainwater collection. Table 1 shows the number of additional functioning improved drinking water sources constructed or rehabilitated during the NDP II period.

The main interventions by the Ministry of Water Resources Development (MoWRD) are the construction (drilling) or rehabilitation of boreholes, together accounting for 50 of the 639 additional water supply systems, and the establishment or rehabilitation of mini-water systems (27.5 percent).

2.4 Economic Development

The Impact of Drought

In recent times, particularly beginning in 2010, there have been repeated droughts in Somaliland due to low and erratic rainfall. Currently, Somaliland is experiencing a drought. The drought has led to a severe reduction in the quantity and quality of grazing pastures and the water available for livestock. The effect on livestock herds has been devastating. Some regions have seen herd sizes fall by over half due to death, distress selling, and low birth rates. As a result, some families have lost their entire herd.

Around half of the population are pastoralists and livestock play a crucial role in supporting their livelihoods. They are a source of income and calories as well as a major capital asset. For many pastoralists, livestock are the only asset they own. Their living standards are intimately connected with the health of their livestock.

Besides a damaging impact on the health of livestock herds, the drought has had a significant direct impact on those who are engaged in agricultural production. It has also had an indirect impact on those working in the non-agricultural sector through reduced economic growth and inflation.

Crop Production

Somaliland’s agriculture is dominated by subsistence farming, mainly dependant on traditional small-scale sorghum-based dryland agriculture (mono-cropping), although maize is also grown, especially in years with better rainfall. Mono-cropping has made soil less productive and is one of the attributed factors to land degradation in traditional farmlands. Most agriculture related programmes focus on emergency response and resilience enhancement, with very few working on agricultural development.

Livestock

Livestock exports represent about 80-90 percent of the total value of all exported goods and services of Somaliland, indicating their importance. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), Yemen, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are the main destinations for Somaliland livestock exports.

The bulk of the live animals being exported are small ruminants (sheep and goats). Saudi Arabia is the main destination for these animals, with 70 percent of the exports taking place during the Hajj season. Based on health grounds, Saudi Arabia imposed a ban on imports between November 2016 and May 2020, based on claims that it found Rift Valley Fever (RVF) in Somali livestock. A second import ban was instituted in March 2020 following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and was ended in December 2022.

The clear drop after the 2016 peak year is explained by the combined effect of the drought and the Saudi Arabia import ban. Over the same period, stable numbers of live animals were slaughtered annually for domestic consumption in the seven urban slaughterhouses (approximately 530,000 goats and sheep, 23,000 camels, and 18,000 cattle per year). In the domestic market, the negative impact of the drought was compensated by the fact that more animals were available for the domestic market due to the Saudi Arabia import ban.

Fisheries

More than 95 percent of fish currently caught in Somaliland are estimated to be from registered national fishing boats, with an estimated 80 percent of this coming through the Berbera Port. Data from other locations (Maydh, Las Khorey) is currently not reliably collected.

International vessels can operate through a locally established partner company and are currently (as of 2021) limited to a maximum of four licensed vessels after a complete ban was imposed by the Ministry of Livestock and Fishery Development (MoLFD) in 2018 and 2019. The growth of the annual catch from international vessels is therefore limited. The official annual catch from international vessels dropped from 830 tons in 2017, to zero during the period of the imposed ban, and back to 219 tons in 2020 and 162 tons in 2021.

The limitations have been imposed for environmental reasons, as MoLFD does not have the capacity to regularly conduct stock assessments and establish sustainable fishing quotas or ensure sufficient oversight to limit the damage to coral reefs.

The fleet of national fishing vessels that were registered with the Fishery Department consisted in 2021 of 245 smaller vessels with an engine capacity of less than 25 hp, 123 vessels with an engine capacity between 25 hp and 100 hp, and only seven bigger vessels with an engine capacity of more than 100 hp

Energy

The recently updated National Energy Policy estimates that 80.7 percent of Somaliland urban households have access to electricity, whereas 20.3 percent of rural and nomadic households have access to electricity. These figures are slightly below the target outcome indicators of the NDP II.

Energy is relatively expensive, which has a negative impact on household income and business development. Efforts by the Ministry of Energy and Mining (MoEM) to reduce the average tariff charged by energy service providers have been a priority and during the NDP II period there has been a reduction of 35 percent, according to a survey in the 9 major towns, which slightly surpassed the 30 percent target.

It is estimated that 16.2 percent of the total installed 150 MW capacity comes from renewable energy sources, considerably above the NDP II target of 10 percent. The main renewable energy projects implemented during the NDP II period include:

- Energy Security and Resource Efficiency Somaliland (ESRES) was a US$34 million clean energy investment and technical assistance programme in Somaliland.

- The Somali Electricity Access Project (SEAP) is a US$2.6 million clean energy investment and technical assistance programme in Somaliland.

- Somaliland Energy Transformation was a US$4 million renewable investment that targeted maternal and child health facilities, schools, and water points in the rural areas of Somaliland.

- A US$2.6 million investment in solar streetlights and renewable energy installations for Las Anod and Erigavo hospitals.

- The Berbera Solar Project that installed 7 MW of solar capacity in Berbera.

In terms of improving the policy and legal framework, the Somaliland Electrical Act was passed by the parliament in 2018 and signed off by the president. However, there are important sections, such as tariff regulation, that were removed by the parliament during the review.

Upon the approval of the Act, the Somaliland Electricity

Commission was appointed, and they are currently regulating the sector. The Commission is currently working to establish the certification and licensing system of the electrical workers and contractors. The MoEM also developed and endorsed the temporary distribution guidelines.

In early March 2017, consultancy services were contracted for the development of a Power Master Plan. This Power Master Plan captures the current situation within the Somaliland power sector as well as suggests ways to improve efficiency. The Power Master Plan of Somaliland was launched in 2020.

Extractives

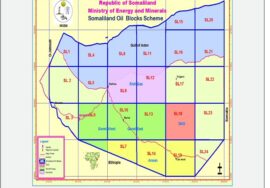

The MoEM formulated and facilitated a multi-client 2D seismic project, which it presented to all international oil companies that have production sharing agreements with government. The first project of the multi-client arrangement was concluded in January 2018, with the acquirement of 3500 km of 2D seismic surveys for Genel Energy on blocks SL6, SL7, SL10, and SL13. The second project was concluded six months later in July 2018, with the acquirement of 800 km of 2D seismic surveys for RAK GAS on block SL9.

In mid-2019, both RAK Gas and Genel carried out seepage analysis surveys. These oil and gas exploration surveys covered 17 percent of Somaliland’s land mass, exceeding the NPD II target of 10 percent. The extractives sector has also implemented numerous mineral exploration undertakings, including the following:

- Small scale jade mining

- Abdulqadir Mining exploration survey

- Dhagax Guure mining exploration survey

- Sheiklh (Sule Malable) mining exploration survey

- Laaso Surad mining exploration survey

- Exploration and small-scale mining of gold in Sanaag

- Siimoodi gemstone project.

2.5 Environmental Management

The following developments are noteworthy achievements during the NDP II period:

Biodiversity Protection

A total of 5,000 km² of land has been gazetted as protected areas and four biodiversity hotspot sites have been identified and evaluated.

In terms of wildlife protection, 90 cheetahs, approximately 40 antelopes, and numerous birds of prey, wild cats, caracals, and about 400 lizards and tortoises were saved. Three wildlife orphanage centres have been established in Dabis, Masalaaha, and Geeddeeble. The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change signed an agreement with Sweden for a project to assist in the establishment of Somaliland’s first marine conservation area, to be established during the NDP III period.

Soil and Water Conservation

Various soil and water conservation programmes have been implemented, including the construction and rehabilitation of 30 berkhads in Togdheer and 11 berkhads in Sanaag, as well as soil bunds, stone terraces, check dams, and gabions. Four sand dams and two earth dams were constructed at Arabsiyo, Dabis, Aw Barkhadle, Diinqal, El Ayfwein, and Balli Gubbedle.

Communal Grazing Reserves

Five communal grazing sites were brought under the management of the local communities of Bancawl, Casuura, Bookh, Aroori, and Tuuyo. An additional 20 potential communal rangeland sites have been assessed, while dozens of illegal private enclosures were eliminated, mainly in the Maroodi Jeex and Togdheer regions. A rangeland demonstration site was established at Illinta Bari.

Forestry and Tree Planting

Approximately 820,000 seedlings were distributed to major urban centres and at least 70 percent of trees were successfully planted. Five new tree nurseries were established in Debis, Geeddeeble, El Afweyn, Ainaba, and Shurko and an additional five nurseries were rehabilitated in Borama, Berbara, Erigavo, Burao, and Hargeisa. Reduction of the Use of Charcoal

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change, with support from its development partners, distributed 15,000 energy-saving cooking stoves, 4,000 liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) cylinders, and 3,000 kerosene stoves covering all regions of Somaliland.

The policy and legal instruments were put in place to introduce a tax exemption for LPG and a tax reduction for equipment related to alternative energy. The ministry has also provided a subsidy for private investors interested in producing charcoal from mesquites (Prosopis juliflora), an invasive tree species in farmlands, especially in the west of the country.

2.6 The Somaliland Development

Fund

The Somaliland Development Fund (SDF) is highlighted here as an excellent example of a jointly-managed development fund under the chairmanship of the Government of Somaliland, leading to the successful implementation of projects in several sectors at the value of almost US$60 million. It has been often recognised as the government’s preferred financing mechanism.

Phase one of the SDF was successfully concluded at the end of 2018 and phase two has been initiated. In total, just under 500 procurement contracts were handled for the supply of goods and services for the design, preparation, implementation, and conclusion of these projects. The vast majority (approximately 90 percent) of these contracts were awarded to local contractors, providing a boost to the Somaliland economy as well as reinforcing entrepreneurial skills and routines in operating under professionally executed contracts.

One important reason for the operational success of the SDF projects is the Project Preparation Facility (PPF) at the SDF Secretariat. Once an initial Project Concept Note is approved, this will unlock financial resources for technical assistance to support the requesting ministry in developing a professionally designed Final Project Proposal with a detailed budget.

The establishment of a Project Preparation Facility could greatly enhance the capacity of ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs) to operationalise the NDP III and formulate properly designed interventions with sound budgets. Lessons could be learned from global funds that work with such a facility, such as the Green Climate Fund.

Chapter 3 MACROECONOMIC ANALYSIS

3.1 Gross Domestic Product

Somaliland started measuring its annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2012, with technical assistance from the World Bank, and later the Government of Sweden and the African Development Bank (AfDB). This coincided with the first National Development Plan (NDP I, 2012-2016). The economy registered a steady growth from 2013 to 2016, averaging 2.6 percent for the period under consideration.

The start of the National Development Plan II (NDP II) coincided with negative growth, with the economy contracting at -1.1 percent, which was mainly attributed to the drought and restrictions imposed on livestock imports by Saudi Arabia. The subsequent two years registered significant growth under the circumstances, with 2.5 percent and 6.2 percent in 2018 and 2019 respectively. As Somaliland has one of the most open economies in the region and is connected to the world economy through trade, COVID-19 impacted the economy in 2020, as in most countries, with a contraction of -3.1 percent.

The GDP at constant prices rose from US$1.9 billion in 2012 to US$2.3 billion in 2020, and GDP per capita (at current prices; 2017 base year) rose from US$544 to US$697. This highlights the significant potential for growth yet to be fully exploited due to economic vulnerability to external related shocks.

3.2 Sectoral Contributions to Economic Growth

Somaliland is attempting to develop non-livestock sources of growth for the economy to create additional revenues for the government to invest in social sectors, as well as to reinvest into the economy. The NDP II had strategies and interventions in agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and the ever-growing service sector, while identifying programmes to promote resilience to maintain comparative advantage in and grow the livestock sector.

Based on estimations from Somaliland’s GDP figures, which is computed using an expenditure approach, sector contributions to GDP in the last two years confirm the growing importance of the service sector. Table 6 highlights the various components based on classifications of the System of National Accounts 2008 guidelines. The major contributions of the three main economic sectors to GDP in 2020 were 8.1 percent from agriculture (production sector), of which livestock clearly stands out, 18.6 percent from industry, and 73.3 percent from services.

The Agricultural and Production Sector

The contribution of the agriculture and production sector to GDP dropped from 8.1 percent in 2019 to 6.9 percent in 2020. The drop is mainly attributed to the impact of COVID-19 that curtailed livestock exports into the main market of Saudi Arabia, as there was limited Hajj and Umrah participation. Somaliland is the Horn of Africa’s largest exporter of livestock – mainly goats, sheep, and cattle – into Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States, particularly during the Hajj. The livestock sector contributes over 75 percent of the total value of exports, as well as to the agriculture sector.

Pastoralism continues to be the dominant economic activity for most of the six regions across Somaliland, creating jobs and employment for the greater part of the population.

There is limited economic activity in forestry, fisheries, and crop production. With a coastline of over 800 kilometres, fisheries are one of the most underdeveloped sub-sectors.

There is just one commercial fish processing factory in the country. Despite livestock’s significant contribution to the Somaliland economy, all three sub-sectors, including livestock, continue to lag due to their strictly subsistence nature.

The Industrial Sector

The contribution of the industrial sector to GDP dropped slightly from 18.6 percent in 2019 to 15.0 percent in 2020. All the sub-groups, i.e., construction, manufacturing, and mining, registered drops in overall activity. The construction industry remains the most buoyant, contributing to 93.4 percent of industry, with both private and public investment in the sector. The construction sub-sector is highly dependent on remittances from Somalilanders abroad. Mining and quarrying contributions to growth remain largely underdeveloped whilst manufacturing is mainly in light industries.

The Services Sector

The contribution of the services sector to GDP increased slightly from 73.3 percent in 2019 to 78.1 in 2020. All sub-sectors showed a great deal of resilience despite the pandemic, with just moderate drops in a few instances. Food and beverages constitute 58.1 percent of the total services sector, followed by other services, which include wholesale and retail, telecoms, financial services, hospitality, etc. Public administration remains strong, especially from the central government, constituting 6.4 percent of the sector, a drop from seven percent in 2019.

Prospects

in the service sector depend on the rebound of activities in accommodation, professional services, administration, remittances (to support consumption), and hospitality, which contracted during the pandemic due to travel restrictions.

The tourism sector could pick up as travel restrictions are eased due to improved health responses, the administration of COVID-19 vaccines and increased international travel.

However, the outlook for the tourism sector remains fragile due to uncertainties surrounding the potential appearance of new variants of the COVID-19 virus and potential need for new travel restrictions.

3.3 Fiscal Operations

The Government of Somaliland’s fiscal position over the last three years of NDP II was strong despite challenges posed by COVID-19 for revenues and unexpected expenditures. In the fiscal year 2019, the overall budget balance (including grants) was a surplus of SlSh 90.4 billion. Due to the pandemic, the deficit widened to SlSh 29.7 billion in 2020, attributed mainly to a reduction in grant flows as well as increased spending on goods and services.

The budget balance was restored from a deficit to a positive of SlSh 97.2 billion in 2021 as economic activities bounced back. Figure 8 highlights the government’s fiscal balances considering grants and loan repayments. The objective of the analysis is to delineate the effect of grants and loan repayments on current efforts to gain a strong fiscal position.

The budget balance (excluding grants) and primary balance (excluding grants and loan repayments) were both positive for the last three years of NDP II. The budget balance, excluding donor funds and loan repayments, was consistently positive, reflecting good fiscal management.

Domestic Revenue

Domestic revenue, as indicated in Figure 9, increased by 26 percent from SlSh 1.8 billion to SlSh 2.0 billion, or 7.9 percent of GDP in 2020. The revenue-GDP ratio highlights the need for significant improvement in revenue generation, as the World Bank’s minimum recommended ratio is 14 percent for Sub-Saharan Arica countries. Tax revenue continued to be the main source of revenue for the government over the NDP II period, accounting for 87.8, 86.8, and 80.8 percent of total revenue in 2019, 2020, and 2021 respectively. The contribution of taxes to domestic revenue is slowly reducing as non-tax revenues grow, a positive development in expanding the revenue base.

Government Expenditures

eral financial institutions, all of the country’s debt is domestic. Additionally, due to an absence of financial assets such as treasury bills and central bank bonds, all loans accrued are mainly arrears accumulated by MDAs and central bank advances. There is an existing debt manual that guides the validation and payment of debt.

Similarly, government expenditure grew in nominal terms alongside revenues. Compensation of government employees continues to be the main expenditure, with a majority going to the security sector. Of particular importance is the increase in project financing from the government over the years, which grew from SlSh 27.7 billion to SlSh 182 billion, an increase of over 500 percent. To address the infrastructure deficit, which is required to spur economic growth, this trajectory must be sustained.

Donor funds using Somaliland’s country systems continue to be extremely low compared against recommendations set out in the Paris Declaration, which encouraged donors to use country systems as opposed to creating parallel structures.

Domestic Debt Market Developments

The domestic debt market remains shallow and is constituted largely of arrears accumulation by Ministries, Departments, and Agencies (MDAs). There is no accessible capital market for the government or private sector to raise required funding for investments. Due to a lack of access to international financial markets and financing from multilat

Total domestic debt payment as of December 2021 amounted to SlSh 86.5 billion, dropping from a high of SlSh 111.9 billion in 2020, a 22 percent reduction (see Figure 11).

3.4 Financial Sector Development

Financial indicators of the banking industry remain within prudential requirements, indicating a well-capitalised and highly liquid industry.

Growth in the banking industry is evident in its asset base.

Total assets grew by 22 percent from 2019 to stand at US$290.6 million by the end of December 2020. Overall, the assets of the banking industry grew by 64 percent from 2017 to 2020. There was also a significant rise in bank deposits from US$120.3 million in 2017 to US$291.1 million by the end of 2020. This is a significant indicator of the banking sector’s liquidity and ability to supply credit to the economy.

Although there is considerable room for improvement, the banking sector’s catalytic role and contribution to the economy is growing. Gross loans as of December 2020 stood at US$184.3 million, up from US$49.7 million at the end of 2017, a growth of 271 percent. Private sector credit growth, a universal indicator of business growth, grew 124 percent in 2020. Unfortunately, there is no data on Non-Performing Loans (NPLs). This makes it impossible to estimate significant asset quality measures, such as gross NPLs to gross loans, provisions to NPLs, earning assets to total assets, etc.

The industry remained highly liquid, with a liquid to total asset ratio of over 80 percent since 2017, reaching a peak of 90 percent at the end of December 2020. This is well above the prudential requirement of 30 percent. This indicates that banks are holding onto significantly more cash than required, possibly due to the lack of safe investment options. The ratio of liquid assets to deposits as of December 2020 was 89 percent, high enough to meet short-term liabilities.

Return on Assets (ROA) and Return on Equity (ROE) from the end of December 2019 to the end of December 2020 rose from 0.8 percent and 7.7 percent to 0.7 percent and 6.9 percent, respectively. The moderate returns could be attributed to excessive liquidity, as some of the liquid assets could be invested for higher returns.

The non-bank financial sector serves the informal component of the economy and is often used as a good indicator of financial inclusion. In Somaliland, non-bank financing is provided by microfinance institutions (MFIs) and mobile financial services. Both are expanding, in volume and in value, contributing to the rapid expansion of the digital financial space.

MFI’s assets, capital, and income continue to grow. Total capital grew by 21 percent from US$5.7 million at the end of December 2018 to US$6.8 million at the end of December 2019. MFIs registered 24 percent and 27 percent growth in total assets and total loans, from US$7.4 million and US$6.0 million in 2018 to US$9.4 million and US4 7.5 million, respectively. Finally, MFIs registered their highest recorded growth rates during this period, rising from US$252,118.47 to US$ 484,867.69, an increment of 92 percent.

3.5 Balance of Payments

The balance of payment is not estimated in Somaliland as the system of national accounts is not fully estimated.

As a result, this section analyses the goods and services of a typical current account, depicting persistent deficits financed through remittances and official flows. The goods account balance is estimated to be at a deficit of US$109.8 million as of December 2021, compared to a deficit of US$106.6 million the previous year. The deterioration in the goods account balance mainly reflects an increase in the importation of goods, which offsets the slight growth in exports.

The services account balance decreased 14 percent, from

In this regard, the stability of the shilling from 2017-2020 a deficit of US$16.3 million in 2019 to US$ 18.6 million in 2020. The widening deficit is attributed to a drastic drop in both tourism and personal travel due to COVID-19.

Both the services and goods accounts persistently recorded increasing deficits from 2017 to 2020. As a result, the trade balance worsened over the same period, exerting more pressure on financing the deficit. As depicted in Figure 12, the trade deficit widened from US$ -93.2 million in 2017 to US$ -128.4 in 2020, representing a negative growth of 38 percent.

The main sources of financing the trade deficit are remittances from abroad and Official Development Assistance (ODA). There is limited data on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Portfolio Investment Flows (PIFs) into the country.

3.6 Exchange Rate Development

The foreign exchange market continues to be awash with liquidity largely due to export receipts and ODA. However, it is equally under pressure as net flows of remittances registered in 2021 were negative.

The Central Bank of Somaliland’s main monetary policy tool to manage inflation is the exchange rate corridor. Based on movements in the market, the bank embarks on open market operations, through auctions, to stabilise the Somaliland shilling. The bank injects more shillings into the market when the value of the currency is considered overvalued (appreciates) against the US dollar. Alternatively, when the shilling depreciates, which impacts price stability, the bank intervenes by withdrawing more shillings using the US dollar. The market volume for US dollars then increases and slightly depreciates against the shilling.

Overall, currency depreciation or appreciation within a five percent band is acceptable, as it is considered non-volatile.bodes well for inflation and overall macroeconomic stability.

The Bank of Somaliland intervened in the market on multiple occasions in 2021 to influence the market rate of the shilling. Overall, the net injection was SlSh 48 billion, indicating a strong performance of the shilling against the US dollar.

3.7 Price Development (Inflation)

Although Somaliland is vulnerable to external shocks that can spike inflation, such as high imports (imported inflation), persistent trade deficits, and exchange rates, inflation has been low and stable over the last two years. Headline inflation has consistently been below double digits since August 2018, when it was 13.6 percent following high spikes in much of 2017 and 2018. Over the last two years, prices have, to a large extent, been stable within the central bank target of single digit inflation. Much of the inflation is driven by food inflation, except from April 2021 to July 2021 as depicted in Figure 15. The price stability towards the end period of NDP II is much more pronounced, as the last six months of 2021 registered subdued prices, peaking at one percent in July 2021.

The rise in food prices is influenced by the increase in “food crop and related items” prices, which increased by 3.7 percent in July and 1.8 percent in August before declining 0.2 percent in September. The other volatile component of headline inflation is energy prices, which also remained low in the last six months, peaking in December at 2.6 percent.

As expected, core inflation is less volatile than food and non-food inflation. This is because core inflation measures fundamental changes in prices of goods and services in the economy, minus the volatile items. For the last six months, core inflation has never reached one percent. In fact, in December 2021, it was constant at 0.5 percent from the previous month. Indeed, the economy has experienced price stability for the past two years, aided by central bank monetary operations which keep inflation at reasonable levels as COVID-19 continues to impact lives and livelihoods.

Chapter 4 MACROECONOMIC STRATEGIES FOR GROWTH

4.1 Introduction

The Somaliland economy continues to grow, riding on the peace dividend as well as the government’s commitment to diversify the economy away from pastoralism. Prospects remain good in the medium and long term. The macroeconomic framework to support growth within the period of NDP III, in line with the objectives of Vision 2030, will specifically include, among others, the following reforms:

- Growth diversification

- Revenue mobilisation and expenditure rationalisation

- Domestic money market development

- Improved monetary policy framework

- Financial sector stability, competitiveness, and safeguards

- Business environment improvements

- Strengthened statistics via an inter-agency macroeconomic working group

4.2 Fiscal Policy

Domestic revenue (tax and non-tax) mobilisation is imperative to generate additional revenue and achieve greater budgetary flexibility, especially on development and project financing. The fiscal envelope will be expanded to increase expenditures on social services and infrastructure development. Options include improving revenue collection and streamlining expenditures to more strategic issues.

Although sensitive for a low-income country, taxation will be fair and non-distortionary, forming the bedrock of sustainable revenue mobilisation.

Revenue Mobilisation

Independent and semi-autonomous revenue authorities have proven to be effective in improving compliance in many areas. As a result, the Somaliland Revenue Authority will be established. Tax exemptions will be streamlined for both inland revenue and customs. The exemption rules and procedures will be strict. There will also be improved tax exemption reporting for inland revenue as part of annual tax returns and partner funds will be incorporated into the budget.

For inland revenue:

- The revenue base will be expanded by encouraging Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) into formal structures and/or improving overall compliance in the informal sector.

- The Integrated Tax Administration System (ITAS) in the Public Financial Management (PFM) reform strategy will be prioritised in phase II of the World Bank project, replacing the PFM Support project. The automation will improve general taxpayer information and, eventually, compliance.

- The capital gains tax will be reformed so taxes will be paid after disposal. It is beneficial to have a specific tax on the sale value or a percentage of the consideration made, whichever is higher. Presently, any gain or loss from the disposal of an asset is included in gross income or the loss is permitted as a deduction of gross income. This is prone to non-compliance.

- Telecoms taxation will be improved by introducing an excise on telecoms, a Global System for Mobile Communication (GSM) tax on all calls, and the standard corporate tax on profits payable by GSM companies.

This will be followed by telecoms audits, possibly with external technical assistance.

In the context of customs revenue:

- In line with the PFM Strategy, the customs department will receive funding to transition to the Automated System for Customs Data (ASYCUDA) system, which will reduce most of the current manual valuation.

- Utilising the Berbera Oil Terminal, and the overall Barbera Corridor, the government will continue to devise strategies to increase imports from Ethiopia, including fuel.

- The taxation regime on khat, cigarettes, and other tobacco products will be overhauled based on World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendations. There will be an ad valorem tax and a specific tax on all tobacco products.

Rationalised Expenditures

With limited domestic resources, the government will rationalise expenditures to be efficient and effective, reducing waste and improving impact.

In line with the PFM Strategy, the government will work on the establishment of the Procurement Authority, working closely with the National Tender Board (NTB) and parliament. This will pave the way to decentralise procurement in government, improving capacity at the MDA level and increasing value for money.

Linking the budgeting process to the National Development Plan will address the mismatch between the annual budgets and the NDP III. Additionally, extrabudgetary expenditures will be reduced to keep arrears at sustainable level by MDAs.

4.3 Monetary Sector Developments

Currently, the only monetary policy tool utilised by the Central Bank is the exchange rate corridor. This requires building foreign exchange buffers as part of the reserve management. There are downside risks to the effectiveness of this strategy, particularly the vulnerability of livestock exports, volatile inflow of remittances, and reduced ODA.

In the near future, the Central Bank intends to adopt a monetary targeting regime using Narrow Money (M1) and Broad Money (M2). It will consider reserve requirements as one of its morphing strategies. A well-capacitated research department, rather than a monetary policy unit, will be established to help the bank’s continuous assessment of the economy to prescribe the right policies for price stability, financial sector management, and economic growth.

On financial inclusion, a credit information system will be established to reduce possible excessive credit concentration and work on creating a platform for guarantees for SMEs. Presently, Somaliland’s banks have too much liquidity. Therefore, financial sector policies to incentivise lending to the private sector will be promoted. This will create a win-win situation, where liquidity could increase yields for banks while providing needed credit to the private sector.

4.4 Financial Stability and

Safeguards

The banking sector is in good condition, but financial inclusion remains limited despite recent gains, especially among women in the informal economy. The sector is dominated by a few large players, organised in an oligopolistic structure, with limited information provided to the Central

Bank on important indicators that gauge asset qualities, such as on Non-Performing Loans (NPLs). The Central Bank will continue to build its supervisory capacity, utilising standard reporting tools for all bank and non-bank financial institutions. There is a need to improve data sharing obligations so that banks and non-banks regularly supply information to the Central Bank, especially on credit distribution. This information will help the government avoid credit concentration and develop incentives to stimulate borrowing in critical sectors of the economy. Besides the building of a credit information system to reduce possible excessive credit concentration and improve inclusion, a platform for guarantees for MSMEs must be created to enhance inclusion. Regulations and the payment architecture for mobile banking need to be improved. Mobile banking services have the potential to improve financial inclusion via an electronic payment platform in the country.

Risk-based bank supervision and the enforcement of prudential ratios must be introduced based on the Basel Committee recommendations. The whole range of financial sector indicators will be subjected to prudential requirements.

4.5 Domestic Currency and the

Debt Market

The government of Somaliland, through the Central Bank, will work on modalities to introduce money markets into the country in line with the principles of Islamic banking, as required by the Islamic Banking Act.

Due to limited domestic resources, much of Somaliland’s development budget comes from international partners.

Domestic revenue is mainly comprised of taxes, especially on international trade. The government doesn’t have access to multilateral financial institutions, hence the need to create an avenue to raise funds both from domestic economic players and Somaliland’s diaspora. This will serve both the government and corporate sectors, as there is a need for a domestic money market to raise capital for investments.

For the establishment of a domestic debt market, strictly based on Shariah-compliant investments, the government will study the model in other Islamic countries and Sukuk markets and adjust for local context. Furthermore, a national development forum on domestic market development will be organised, including discussions on establishing diaspora bonds, a financial tool available in other countries in the region.

Prior to the establishment of the money market, a debt law must be enacted. The law can legislate the “golden rule principle”, taking debt only for capital expenditures.

Moreover, it can introduce an explicit debt anchor by, for example, targeting a specific debt-to-GDP ratio. A debt management strategy will then be developed based on the proposed legislation, based on the objectives of contracting debt at the lowest cost and risk to future generations.

4.6 Improving the Business

Environment

The business environment in Somaliland remains good, but improvements will further support private sector-led growth. The World Bank’s 2012 Doing Business Index (DBI) ranked Hargeisa 174 out of 183 in doing business. Since then, there was no other DBI report that included Somaliland. Recently, the Ministry of Finance Development conducted a study of the business environment in the county, based on the recommendations in the 2012 DBI report.

This study concluded that:

Momentum needs to be sustained in the following areas:

- The number of days it takes to register a business has been reduced and Somaliland is now competitive among East African countries. Only Rwanda is doing better, with just 4 days.

- Continue the one-stop shop for investors.

Improvements are needed in the following areas:

- Improvements in the energy sector will be geared towards reducing costs, establishing a national grid, improving the energy mix for sustainability, strengthening regulations, and enhancing standardisation.

- Access to credit remains a challenge – out of the eleven indicators in the 2012 DBI report, access to credit was ranked the lowest. The policies mentioned previously under the financial sector are expected to improve this indicator.

- Although competitive in the region, paying taxes will be made more efficient for the taxpayer and less costly for the government to collect, especially for land and buildings. There will be an inter-agency committee to review reforms and create a roadmap on how to address reforms, if needed.

- Land banking for investment will be prioritised based on the recently approved Land Policy in 2021, which establishes reforms to the land tenure system.

Chapter 5 MAINSTREAMING CLIMATE CHANGE IN NDP III IMPLEMENTATION

5.1 Introduction

predict the weather. However, these typical climate patterns no longer exist or are more difficult to predict because of Somaliland is highly vulnerable to the risks of climate change and extreme weather conditions. The NDP III comes at a time when Somaliland has experienced five consecutive failed rainy seasons, and forecasts indicate that the rainfall in 2023 will be below the average, devastatingly impacting the ecosystem. These droughts and shocks are increasingly becoming recurrent and disproportionally affecting vulnerable groups, including women and girls, children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and other marginalized groups. Frequent and intense droughts undermine food security and worsen livelihood conditions, fuelling societal grievances, increasing competition over scarce resources, and exacerbating existing community tensions and vulnerabilities. Climate change has complex and interlinked implications for natural resources, peace and security, human health, migration and displacement, gender equality, and vulnerable and marginalized groups.

Hence, the NDP III is adopting a climate resilience approach in its implementation by mainstreaming climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies to respond to the needs and priorities of different communities.

Compared to other nations, Somaliland emits relatively low levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere but suffers from the impact of global greenhouse gas emissions. In the NDP III, Somaliland is committed to reducing the emission of greenhouse gases by increasing the share of renewable energy sources and generation and planting trees in urban and rural areas.

5.2 Climate Change Adaptation

Approaches

The NDP III will embed climate change adaptation approaches in its implementation to combat the climate crisis and achieve Somaliland’s national development priorities.

Climate-resilient Infrastructure

Somaliland aims to build advanced infrastructure that enables economic and social development while facilitating local, regional, and global trade. The priority is a domestic road network that connects the different parts of the country. 37.71 percent of the cost of the NDP III is dedicated to building to climate-resilient infrastructure such as roads, bridges, ports, airports, and telecommunication lines that can withstand shocks from extreme climate impacts. Investing in resilient infrastructure is a key strategy for adapting to climate change and will save billions of dollars worth of damages while reducing vulnerabilities. More resilient infrastructure assets pay for themselves with extended lifecycles and more reliable services.

Early Warning Systems

Somaliland relies on regional institutions for climate information and early warning systems. Although the Ministry of Agriculture Development (MoAD) keeps weather records at specific meteorological stations across the country and NADFOR disseminates periodic weather information through radio, rural communities seldom access this information to take necessary actions. Historically, rural communities have relied on natural indicators like wind direction, the location of stars in the sky, and cloud movements to climate change. Early warning systems are becoming a critical adaptation measure that can reduce the damage of droughts to the economy, specifically for agro-pastoralists and vulnerable groups. In the NDP III implementation, the Government of Somaliland will establish the National

Meteorological Agency (NMA) for the documentation and timely dissemination of climate information to stakeholders to prepare for eminent droughts and other climate patterns.

Water Supply and Security

Recurrent droughts from declining rainfall have significantly reduced the availability of water in Somaliland. Water scarcity kills livestock, dries crops, and forces pastoralists and agro-pastoralists to move from one place to another in search of water and pasture. In urban areas, families prioritise water for cooking and drinking and forgo bathing and washing clothes during dry seasons when water is scarce and expensive. In its implementation, the NDP III invests in rainwater harvesting systems to increase water availability.

These measures will be complemented by the installation of green technology, such as solar water sources, to improve water supply sustainability and reduce the cost of operations and maintenance. It is also vital to adopt a policy of Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM), which considers the entire water cycle from source and distribution to treatment, reuse, and return to the environment in a sustainable manner

Natural Landscape Restoration and Reforestation

Over the past two decades, the degradation of natural resources and deforestation, mainly driven by charcoal production and overgrazing, have rapidly increased Somaliland’s vulnerability to climate change-induced droughts and desertification. The Environment chapter of the NDP III outlines nature-based solutions or ecosystem-based adaptations for the climate crisis. This includes planting trees in urban and rural areas and on mountain slopes and planting mangroves in coastal areas to significantly reduce heatwaves, provide natural sea defences from storm surges, and prevent desertification.

Sustainable Production Practices

In Somaliland, most food production depends on weather conditions as a majority of the country’s agriculture is rainfed. Changing rainfall patterns make it difficult for farmers to determine when to sow the seeds, which can lead to reduced food production and availability. For example, farmers typically sow their fields in February each year and expect rainfall between March and May, while finally harvesting in July or August. However, infrequent rain and shifting rainfall patterns lead to smaller yields or, in some cases, total crop failure for the year. The Production chapter of the NDP III outlines the implementation of sustainable agricultural practices to achieve food through strengthening communities’ resilience and adaptive capacity, while also protecting marine resources and adopting climate-resilient livestock management approaches.

Considerations for Vulnerable Groups

The NDP III reflects the needs and priorities of the vulnerable group in the Cross-cutting Themes chapter while also being inclusive in its implementation. Implementing the NDP III strengthens vulnerable groups’ resilience and reduces their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related events and shocks. For example, the implementation of national social protection systems and measures for vulnerable groups, including women and children, people with disabilities, displacement affected communities, and people living with HIV/AIDS, will strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters. Moreover, ensuring that vulnerable groups have equal rights to economic resources, access to basic services, and ownership and control over productive resources will further insulate them from climate-related crises.

Long-term Planning

The NDP III envisages climate adaptation solutions that could be more effective if integrated into national development policies, strategies, and plans. Somaliland will develop a National Adaptation Plan (NAP) which will consolidate and harmonize strategies, plans, and policies to strategically prioritize adaptation needs to address climate change-related crises. The NAP will inform government decisions on investments and regulatory and fiscal framework changes and raise public awareness of climate change risks. Given the unique case of Somaliland, the government will work with the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) to explore ways to support the development of the NAP, which will also be used to improve adaptation elements for Nationally

Determined Contributions (NDCs), which are a central part of the Paris Agreement.

5.3 Financing Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

Somaliland is committed to upholding the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and other international treaties in tackling the risks of climate change.

Although Somaliland cannot directly participate in global climate change discussions as a state, it can still participate and play an active role through the UN, regional bodies, friendly states, and other multilateral agencies. For example, in collaboration with the UN Development Programme (UNDP), the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change (MoECC) organizes annual climate change forums where participants exchange updates about the impacts of climate change and adaptation strategies. The MoECC will expand these forums by inviting all relevant public and private institutions, development partners, and think tanks and research firms. The MoECC will also organize regional events to cascade climate change discussions to affected communities and their governance structures. Furthermore, the MoECC will coordinate with relevant stakeholders, such as UNEP, to formulate the NAP that will guide the national adaptation needs.

Like many other developing countries, Somaliland needs to finance its climate change mitigation and adaptation measures. There are several global funds available for climate change mitigation and adaptation. While Somaliland may not be able to benefit directly from these funds as a state, it can still access financing through the UN, specifically UNEP, and other multilateral agencies.

These funds include:

- The Global EbA Fund provides grants to innovative approaches to ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA).

- The Adaptation Fund Climate Innovation Accelerator (AFCIA).

- The Green Climate Fund (GCF).

- Strengthening Endogenous Capacities of Least

Developed Countries to Access Finance for Climate Change Adaptation (UNI-LEAD) and others.

Moreover, the announcement of a global Loss and Damage Fund at the most recent United Nations Climate Conference (COP27) is an opportunity for Somaliland and other developing countries to finance their climate mitigation and adaptation needs. Since Somaliland is likely to face restrictions and challenges in accessing climate change adaptation and mitigation financing, the country needs to develop an innovative strategy to coordinate with UN agencies and other multilateral agencies to benefit from available funds.

Chapter 6 ECONOMY SECTOR

6.1 Introduction

Table 9: Policies and legal instruments developed during NDP II Somaliland’s Vision 2030, with respect to the state of the economy, is to be “a nation whose citizens enjoy sustained economic growth and reduced poverty levels”. To achieve this objective, the government will prioritise expenditures on core sectors such as health, education, and water. The emphasis will be on improving human capital as a bedrock of development. Furthermore, development will always be anchored on sound macroeconomic policies and enabling factors, such as trade facilitation and investment policies, which will lead to job creation and ultimately improve livelihoods through increased incomes.

The anchor of the Somaliland economy used to be livestock and livestock-related activities, but over the years this has shifted, at least in terms of market value, to the service industry. This is a common trajectory of economies in Sub-Saharan Africa – skipping growth in industrialisation and instead focusing on services.

In the services subsector, the dominant players are retail trade, telecoms, tourism, and financial services. Remittances play a catalytic role in the economy and are supported by the large diaspora population. Remittances and the export of livestock ensure a steady supply of much-needed foreign currency to finance the persistent account deficit.

The economy is growing as an important logistics hub for the Horn of Africa, riding on the Berbera Corridor and the peace dividend. The successful Dubai Ports World investment in the Berbera Port and a logistic hub by trading giant Trafigura are good indications of the investment climate in the country. Investments in fish processing from artisanal fishing can be an important source of value added in the economy.

Notwithstanding these gains, Somaliland’s economy remains vulnerable to shocks. To grow on a sustainable path, a reform agenda should be pursued to improve the enabling business environment. A key component of this is expanding the financial sector to support economic growth, which will be complemented by public sector reforms.

6.2 Situational Analysis

The NDP II period witnessed successes and challenges regarding the economy. Although external factors continue to hinder the growth of the economy, challenges also remain on the domestic front. This section highlights the progress as well as the challenges in this sector.

Policies and Legal Reforms

The government’s role in a typical liberal economy is to create an enabling environment through appropriate policies and legal instruments for the private sector to prosper, as well as to address market failures and the provision of public goods.

The reforms in Table 9 highlight the commitment of the government to continually improve the business environment for improved inclusive economic growth.

Public Financial Management

Public Financial Management (PFM) was driven by its reform strategy, which has several important reform programmes, i.e., in the budgeting process, increasing domestic revenue, automating the country’s payment system, and building the capacity of public services to better manage the country’s finances.

The Ministry of Planning and National Development led a prioritisation process of Somaliland’s NDP II (2017-2021), and subsequent budget cycles were informed by these outcomes. The Ministry of Finance Development has also engaged with communities and held public hearings on the budgetary process to enhance citizen engagement and accountability. One of the PFM targets included improving human capital, IT infrastructure, and automation, as well as legal and regulatory frameworks. This has been partially achieved, as mentioned in the policies and reforms subsection.

The reforms in Table 9 highlight the commitment of the government to continually improve the business environment for improved inclusive economic growth.

Public Financial Management

Public Financial Management (PFM) was driven by its reform strategy, which has several important reform programmes, i.e., in the budgeting process, increasing domestic revenue, automating the country’s payment system, and building the capacity of public services to better manage the country’s finances.

The Ministry of Planning and National Development led a prioritisation process of Somaliland’s NDP II (2017-2021), and subsequent budget cycles were informed by these outcomes. The Ministry of Finance Development has also engaged with communities and held public hearings on the budgetary process to enhance citizen engagement and accountability. One of the PFM targets included improving human capital, IT infrastructure, and automation, as well as legal and regulatory frameworks. This has been partially achieved, as mentioned in the policies and reforms subsection.

Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises

Micros, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) play a key role in inclusive growth and employment. In Somaliland, MSMEs are enterprises that employ less than 100 people and have sales turnover or total assets of less than US$500,000.

MSMEs contributed significantly to the post-war recovery in Somaliland following independence and remain a core element of the country’s private sector-driven economy.

A 2017 study by Cardiff University and Gollis University showed that most enterprises in Somaliland are informal and involved in trade. The study estimated that in Hargeisa alone, the informal economy provides 77 percent of the city’s total employment. To facilitate the ease of doing business, the Ministry of Trade and Tourism has established a Business Information Centre (BIC), or Xogsiiye-9444, aimed at providing information to small businesses. The BIC provides information across Somaliland in Somali, English, and Arabic on business start-up practices, access to finance, and business development services.

Following the approval of the MSME Policy 2019, the ministry drafted a roadmap for implementation and established a technical working group to guide the process.

The Ministry of Trade and Tourism established a business licensing inspection team that has been undertaking inspection activities since 2018 to ensure that all types of businesses operating in the country legally exist and are registered. This measure aims to reduce the growing number of unregistered and unlicensed enterprises.

The one-stop shop platform for business registration and licensing was established in 2021, which aims to ease the process of registering businesses by both national and international investors. This will help streamline and automate business registration as well as increase certainty and transparency in setting up businesses, which will increase investor confidence.

The government extended COVID-19 support to businesses in 2020 by cutting the cost of registering a business in Somaliland by both citizens and foreign nationals by 50 percent. In addition, 20 start-ups were granted a 65 percent reduction on business registration and licensing fees.

Tourism

On tourism, the government undertook certain measures primarily linked to the protection and preservation of historical and archaeological sites in Somaliland. Sites that have been protected include Laas Geel, Dhagah Kuurre, Abbasa, Qiblatayn, Dhagah Nabi Galay, and Old Amoud, among others. These measures are geared towards contributing to their long-term preservation, especially the Laas Geel heritage site, which is being promoted as a tourist attraction so it can to be better integrated into the local economy.

Trade and Investment

The Investment Policy 2019 and the Investment Act (Law No. 99/2021) introduced measures to promote, strengthen, and streamline foreign and domestic investment in Somaliland, as well as improvements to productivity and competitiveness. The Berbera Corridor is considered a strategic trade and transit route for the Horn of Africa and beyond.

To leverage this opportunity, the Government of Somaliland established the Berbera Special Economic Zone (SEZ), which extends 12 km from the Port of Berbera, to be the leading integrated maritime, logistics, and industrial hub in the Horn of Africa. The Somaliland Special Economic Zones Law 93/2021 was passed in 2021 and aims to provide local and foreign investors with a conducive and competitive environment for investment and trade.