Somali clan elders and institutions in the making of the of Somaliland

Appropriate ‘governance-technology’?

Somali clan elders and institutions in the making of the ‘Republic of Somaliland’

Summary

Can informal ‘traditional’ institutions help to build more legitimate, ac- countable and efficient states and governance? This article aims to con- tribute to that emerging discussion by unraveling the story of ‘Somali- land’, a self-declared independent republic which seceded from civil war- ridden Somalia in 1991. The Somaliland secession seems to have been instigated by ‘traditional’ clan leaders. The clan leaders were also responsible for several instances of political reconciliation between groups competing for power and resources in the region. The political weight of these clan leaders in the new polity had important repercussions for its institutional make-up. Somaliland started out as a clan-based politico-institutional arrangement, with an important role for ‘traditional’ clan leaders, albeit in a ‘modern’ framework: a ‘state’. The article examines the dynamic between these ‘modern’ and ‘traditional’ components and the evolution it underwent from Somaliland’s declaration of independence in 1991 to 2007. It will discuss ways and means in which ‘modern’ and ‘traditional’ institutions and personnel co-exist, overlap and become reinvented in the context of political competition in the newly founded ‘state’.

State-building in Africa is back on the agenda. After a spell of apparent consensus on the need for ‘minimal states’ in the 1980s and early 1990s, the new meta-narrative in international development prescribes sound state making and institution building as a precondition for market-led economic development (Maxwell 2005: 7). State- and institution-building in Africa, however, represent a serious headache to international policy makers. Ever since colonial times, imported formal institutions associated with Western conceptions of the state seemed to struggle with a lack of legitimacy, ac- countability, transparency and efficiency. Moreover, often their functioning appears to be compromised by informal (‘traditional’ or ‘customary’) institutions. Consequently, these informal institutions have long been considered as remnants of pre-modern times standing in the way of developmental progress. Today, however, informal institutions are beginning to attract the interest of the international policymakers who have worked so zealously to discard them. This is reflected in new policy research by big international players such as the World Bank and OECD’s Development Assistance Com- mittee (DAC), which have started to investigate African informal institutions in a different light (e.g. Dia 1997, Chirayath et al. 2005, Jütting et al. 2007). In- formal institutions are no longer simply dismissed as ‘obstacles’. They may just become ‘opportunities’ or even ‘tools’, potentially useful in fostering good governance and in ‘fixing’ faulty markets and states. This new thinking in terms of policy seems to have been inspired by the numerous instances of academic research analysing the causes, effects and cures of so-called ‘failed states’ (e.g. Zartman 1995, Chabal/Daloz 1999, or Herbst 2000). As pointed out by Keyd and Buur (2006: 2) the resurgence of informal institutions, in particular the political rise of ‘traditional’ or ‘customary’ chiefs, can to an important extent be attributed to the conditions underpinning failed states, notably those referring to conditions of unsuccessful nation-building and in- ternal conflict. In instances where the state lost control over its citizens (or failed to establish control in the first place), informal ‘traditional’ authority structures have filled the gap. In some cases, African governments have turned the outcome of a ‘failed’ (or ‘weak’) state into a means of coming to terms with it, resulting in various degrees of what Keyd and Buur have called ‘re-traditionalisation’ (Keyd/Buur 2006; Skalnìk 2004).2 This strategy also appears to appeal to international development policy makers.

Can informal ‘traditional’ institutions indeed help to build more legitimate, accountable and efficient states and governance? If formal institutions are absent, do not work well or lack popular acceptance, could informal institutions be used as ‘patches’ to repair them and help them function according to the donors’ standards? This article aims to contribute to that emerging discussion by unravelling the story of ‘Somaliland’, an instance of endogenous state-building where informal institutions appears to have played a prominent part. Somaliland counts as a successful case of African state-building. Since Somalia’s state collapse of 1991 the south of Somalia and the capital Mogadishu have sunk into a desperate quagmire of lawlessness and violent politico-economic competition, while the hitherto unrecognized Republic of Somaliland ‘looks, smells and tastes like a state’ (Bryden 2003). Since 1993, it boasts a functioning government with a president, a cabinet of ministers, a bi-cameral parliament, a national judiciary and a national army. Somaliland claims a territory, enacts laws, raises taxes and has even managed to organise three democratic elections: that were local (2002), presidential (2003), and parliamentary (2005). All has been achieved without international political interference and with only extremely modest technical or financial assistance. When asking in Somaliland’s capital Hargeysa how this has become possible and what makes Somaliland different from Southern Somalia, the reply will almost invariably amount to: ‘the clan elders have been of crucial importance’. Indeed, in the process that has led to the emergence of the new polity, ‘informal’ institutions – or more specifically: the institutions associated with the Somali clan-system – have been highly visible.

This article is based on fieldwork carried out in Somaliland between March 2002 and May 2003.3 It presents a discussion of the process leading towards the consolidation of the new polity and an analysis of its current nature. Looking at the case of Somaliland it will become clear that neither in- formal nor formal institutions are ‘empty’ of-political elements. They are part of a larger political process. In that process, formal and informal actors and institutional ‘spheres’ overlap, co-operate and compete. Borders between the informal and the formal sphere are not fixed. It will be shown that in the case of Somaliland, setting or shifting borders between formal and informal spheres has been an instrument in the struggle for political power and con- trol, which has led to the emergence of the institutional and political make- up of the Somaliland Republic as it stands today. Taking this into account, it (nevertheless) becomes clear that the scope for straightforward instrumentalisation of ‘informal’ institutions as tools to fix failed states is limited. In contrast to tools, informal institutions as such can not be readily manipu- lated. Neither should international policymakers hope to avoid the inherently messy political nature of state-building or institution-building by presenting it as a technical fix.

In the following I shall outline how clan-elders and institutions became involved in the process of political reconstruction leading to the establishment of Somaliland as a ‘hybrid’ state. Then I present an analysis of its evolution to a ‘constitutional democracy’ against the background of local political competition and nascent Somaliland nationalism. Finally, I shall discuss the nature of the Somaliland state today as well the relevance of the Somaliland case for future policy.

State-making under a tree: Somaliland as a modern-traditional ‘hybrid’

Somewhat ironically perhaps, the origins of the Somali clan institutions which became a contributing factor to Somaliland’s state-building are profoundly connected to the context of statelessness of the pre-colonial era. The Somali political system was adapted to a thinly populated region inhabited by a dispersed nomadic people, who did not sustain central governance. Relations between roaming nomadic families which were part of larger descent groups (clans) were regulated via heer4. As Somali traditional law, or in fact Somali ‘social contract’, heer constitutes unwritten sets of essentially ‘private’ laws governing the relationship between particular descent groups: in the absence of a higher authority able to enforce laws. All matters between de- scent groups or groups are subject to agreement, contract and compensation.

Liability is collective. For example, if a man kills another man, the descent group of the killer is supposed to compensate the descent group of the victim for their loss or to face retaliation from the victim’s group. The usual price for an adult man is 100 camels or its equivalent in cash. Similar laws and precedents exist for incidents of theft, rape, access to pasture and so on. Heer is made, applied and transmitted by the clan elders, i.e. the clan’s adult married men who decide on an egalitarian basis and are collectively responsible for the affairs regarding their descent group6. I.M. Lewis, the British anthropologist whose 1961 work on the Northwestern Somali still massively im- pacts on current analyses of Somali politics, affectionately called this stateless form of governance ‘a pastoral democracy’ (Lewis 1961/1999). Somali independence in 1960 signalled the inception of formal state structures resulting in the informalisation of the ‘traditional’ institutions associated with the Somali clan system. Subsequently, the military regime installed by the 1969 military coup led by General Siyyad Barre formally (yet unsuccessfully) out- lawed ‘traditional’ clan institutions and even clan allegiance as such, arguing that modernisation and development required national unity.

What happened after the collapse of the Somali state apparatus in 1991? How did the clan elders re-appear so prominently on the political stage in the Northwest? Obviously, state collapse did not imply a simple return to the pre-colonial situation, as if the entire post-colonial political development was somehow deleted. Neither did the clan elders re-appear ‘out of the blue’, spontaneously taking charge of political affairs and governance when the state collapsed. The way for their involvement had been paved long before the actual state collapse, notably during the first decade of the Somali Civil War, beginning in the early 1980s. The northwestern region became one of the first theatres of conflict in the war. For several years government troops loyal to General Siyyad Barre’s military junta were pitted against the militia of the Somali National Movement (SNM). The SNM guerilla movement started in 1981 as a reaction against the perceived power concentration of the Barre regime, which allegedly excluded politicians, military officers and businessmen of the Northwestern Isaaq. SNM had been instigated by disenfranchised Isaaq cadres in the Diaspora. In order for them to stand a realistic chance of winning their guerilla war, they needed local support within Northwestern Somalia itself7. SNM’s leadership actively sought the endorsement of the Isaaq clan elders inside Somalia (Prunier 1990: 113). In re- turn for their moral, logistical and military support the clan elders were given a voice in the movement. From then on SNM’s administrative structures would include an advisory body of clan elders, representing the various sub-clans of the Isaaq. The body was called the ‘Guurti’ and its members were self-selected. Technically, they were just ‘elders’, yet interviewees tended to refer to them as ‘politically active clan elders’, pointing to the fact that these elders involved themselves with matters superseding ‘traditional’ clan affairs. Because of the existence of a modern organisation such as SNM, drawing exclusively on Isaaq fighting power, these elders had become in- volved with Isaaq-wide politics rather than with ‘traditional’ clan affairs conducted at a grassroots level of political aggregation.

In the field, the support for SNM became near-universal, especially after Siyyad Barre’s air bombardment of the Northwestern cities Hargeysa and Bur’o in 1988. The Isaaq clan elders on the ground became deeply involved and actively participated in the war against government troops and their ‘auxiliaries’, makeshift militia from the Dulbahante, Warsangeli and Gad- abuursi clans (Prunier 1990 : 116). As a result of their contributions to the war effort, the political weight of the elders in the field and in the SNM Guurti markedly increased. So did the weight of ‘traditional’ clan leadership and institutions. Upon the collapse of the military regime in 1991, the clan elders took a clear position confronting the SNM leadership. The SNM Guurti sup- ported the rank-and-file guerilla fighters who had fought under the SNM banner in their bid to force SNM’s politicians to abandon their claims on a share in the new Somali national government to be formed in Mogadishu. Somaliland was proclaimed independent (Bryden 2003). Moreover, the increased political weight of traditional clan leadership and institutions al- lowed for a swift return to peace in the Northwest. The Dulbahante, Warsangeli and Gadabuursi, whose clan-based militia groups had fought alongside Barre’s army, had lost the war. Yet, thanks to the involvement of Isaaq clan elders and institutions in the war and in SNM, it was possible to approach the parties who had lost in a particular manner. Rather than approaching each other as political competitors, the former adversaries approached each other via traditional institutions – as clans (Farah and Lewis 1993).

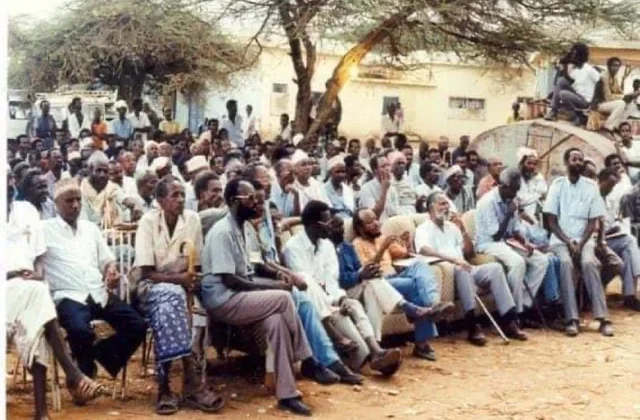

The elders of the respective sides dealt with death, injuries or lootings via negotiation and reconciliation mechanisms according to heer, Somali traditional law. In some cases the traditional peacemaking meetings were a mat- ter of clan elders sitting under a tree hammering out a peace deal between two pastoral groups. In other cases, traditional peace-making was raised to a clan-wide and region-wide reach: in these cases, the negotiators were not exclusively elders from a traditional pastoral background; they were usually ‘politically active elders’ and urban power brokers with modern occupations – former civil servants, businessmen, intellectuals, military men or politicians (Bradbury 1996). Referring back to heer and traditional institutions, however, allowed the negotiators of the involved clans to restore relations and to settle war damages, without having to resort to formal courts, war tribunals or other instruments for restorative justice that did not exist. The involvement of ‘modern’ political and economic actors in the ‘traditional’ peace-making process was in fact a prelude to the celebrated ‘hybridity’ of the new political system that would be born out of it. Thanks to the particularity of that proc- ess, however, none of the former enemies had to lose face and large scale fighting between SNM and non-SNM clan-militia ceased. A portion of the political leaders of the non-SNM clans even appeared to subscribe to Somali- land as a political entity – their representatives were incorporated in the new Somaliland government.

Once more, ‘politically active’ clan elders played a pivotal part in the episode that followed. The new SNM-led Somaliland government failed to establish control. It succumbed to an internal power struggle among compet- ing political actors within the Isaaq over the control of Berbera seaport, a strategic economic asset, vital for government income. What had started as a political conflict between various groups of SNM cadres (politicians as well as military commanders) degraded into an armed fight among the militia of their respective clans. The war, which signalled the end of the SNM government and SNM altogether, was ended by the intervention of the elders. The Gadabuursi elders convinced the Isaaq elders to start negotiating amongst themselves in order to broker a cease fire (Farah and Lewis 1993). The Isaaq elders eventually obliged. Subsequently, the Guurti of the now defunct SNM jumped into the political vacuum. It took over the political initiative and called a national conference of Somaliland clan elders and representatives in Boorama, a Gadabuursi market town.

The conference was held in Boorama on the invitation of the Gadabuursi elders who had mediated in the intra-Isaaq conflict. According to custom, the community hosting a clan meeting has to facilitate it and has to provide housing and catering for the attending elders. Local Gadabuursi businessmen footed a substantial part of the bill for the conference which ended up lasting six months, from January to May 2003. The delegates gathered under trees in the vicinity of the main conference venue and discussed whatever issues they had with each other – as would happen when holding a number of parallel ‘traditional’ clan meetings. Yet, while the form of the conference was ‘tradi- tional’, the substance was indisputably innovative. While normally clan meetings would take place on much lower levels of political aggregation (i.e. descent groups or sub-clan groups), this was the first time ever that a clan conference took place on a ‘national’ scale, bringing together delegates (‘tra- ditional’ elders as well as power brokers such as politicians, military men, etc.) of the different clan families. They were assisted in their work by younger professional clansmen to do the administration, to take minutes or to prepare meetings. Rather than being formally mandated by their clans, the delegates were self-selected, with the clan elders sitting on the Guurti in con- trol of the process (Fadal 1996 and interview Mohamed Ibrahim Warsaame ‘Hadraawi’ 16.04.03).

Organising and overseeing the negotiations between political players within a ‘traditional’ framework (that of a clan conference), allowed the eld- ers on the Guurti, who had filled the power vacuum after the demise of the SNM, to keep on top of the process. They succeeded in formalising their po- litical and institutional role in what was celebrated as a ‘hybrid’ political con- struction. The Boorama delegates agreed to the introduction of a ‘hybrid’ presidential system with a bi-cameral parliament, the latter of which con- sisted of a house of representatives and a house of elders, or Guurti. Mem- bers of both houses were appointed through their clan’s political channels and subject to their clan’s fluctuating political dynamics. The new political system featured the Guurti as the highest organ of the state, the final arbiter in institutional and political conflicts (SAPD 2002). The new president elected by the conference delegates was Mohamed Ibrahim Egal, a veteran Isaaq politician. Egal had been a former prime minister under the 1960s civil re- gime. Deposed by Siyyad Barre’s military coup, he spent some time in prison, but was later rehabilitated as Somalia’s ambassador to India. Egal had a good reputation and stature as an elder statesman. It was hoped that this would enhance Somaliland’s position in the Horn. Even more impor- tantly, Egal had never been involved in the SNM, nor had he been party to

any of its politico-military factions fighting for political power in Somaliland. The elders of the Guurti considered him a trustworthy partner (ICG 2003, and interview Mohamed Rashid Sheikh Hassan 03.04.03). Little did they an- ticipate the impact the new president was going to have on the political posi- tion of the Guurti and the Somaliland clan elders in general.

Claims to ‘modern’ statehood: the hybrid recaptured

In the hybrid state Somaliland had become, the Guurti was invested as the ul- timate peace keeper in the country. Moreover, as a chamber with legislative power, it was part of the national government. The Boorama conference had been the elders’ moment de gloire and the apex of their political power. It is in- teresting, however, that the particular institutional arrangement that resulted from Boorama, seems to have contributed to their gradual but irreversible political displacement as independent, pivotal political actors. Under the ae- gis of the Guurti, the 1993 Boorama Conference laid Somaliland’s new insti- tutional foundations and settled issues concerning the division of power be- tween competing political factions. The outcome of the Boorama conference was promising: a wide consensus was reached and Somaliland now seemed ready for take-off. Arguably, Boorama signalled the birth of something like a Somaliland consciousness, some kind of national identity and a sense of statehood, at least among the Isaaq and the Gadabuursi. The Gadabuursi elders had been intensely involved in forging a political compromise be- tween competing Isaaq politicians and their respective clan constituencies. By saving Somaliland from civil war, the Gadabuursi gained a more impor- tant stake in it. Consequently, Somaliland could no longer be perceived as a merely Isaaq-driven political entity. While the Boorama Conference was go- ing on, nascent ‘Somaliland consciousness’ was further enhanced by the pro- jected deployment of 28.000 troops by UNOSOM II in a bid to pacify and re- unite Somalia (Indian Ocean Newsletter 13.03.1993)10. The idea of foreign troop deployment on Somaliland soil, let alone re-unification with the South was resented by most Somaliland political actors involved at Boorama. This embryonic popular sense of nationhood and more importantly, statehood, was masterfully nurtured and instumentalised by Egal.

President Egal immediately consolidated his position by mobilising a critical amount of financial resources. Working through his own Habar Awal sub-clan of the Isaaq, he secured a loan of 3 million USD from Somaliland businessmen based in Djibouti. The club of businessmen consisted of about 10 big traders, some of whom had been present for a long time on the Soma- liland market, where they were mainly involved in foodstuff and cigarette imports and in hide and skin exports. Others had joined the market after the Boorama Conference in 1993. Except for two of them, the traders were all Habar Awal. In return for the loan, the traders would be granted a tax break for imports into Somaliland via the port of Berbera, which was controlled and managed by Egal’s own Habar Awal clansmen (Marchal 1996 : 75). With the loan, Egal paid for the demobilisation of SNM militia, as well as for the personnel of the new Somaliland government and administration – all of whom were entitled to a salary. With a further financial input from the Ha- bar Awal traders, he introduced a new currency, the Somaliland shilling, which replaced the Somali shilling as legal tender. For both parties this was a hugely profitable move, financially as well as symbolically (De Waal 1996; Africa Confidential 31.03.1995).

Almost immediately, Egal’s position was challenged by competing ac- tors from the Habar Yunis sub-clan of the Isaaq, who felt politically and eco- nomically disenfranchised. A fresh armed conflict ensued. Egal, however, proved able to hold his ground and was even able to strengthen his position, politically as well as institutionally, drawing on superior financial resources, Somaliland nationalism, a statist discourse and clan politics. Predictably, during the conflict, fighting took place. Some of it involved Habar Yunis mi- litia, fighting government regulars aided by Habar Jallo militia. Fighting also took place between Habar Yunis and Habar Jallo militia as such. Militia of other Isaaq clans were involved in the war as well. Yet, the fighting did not totally paralyze the country or the state’s institutions. Egal was in control at all times, embodying the realm of the state founded by the representatives of the Somaliland clans. To be sure, Egal took care to keep balancing and work- ing politics through clan channels, but he was able to do so on his own terms. The clan elders had become all but sidelined. While during the previous con- flict the elders of the Guurti had played a crucial role in peace-making and power-brokering between competing political factions, now they had lost the political initiative. They were part of the government, Egal’s government, and as such considered partisan (Bryden 1994).

As the war between competing politicians fizzled out after two years or so, clan elders on the ground started negotiations amongst each other, out- side the realm of the state or the political competition over state control. As had been the case in the former episode, clan elders successfully brokered a ceasefire and war reparations between the clans of the militia fighting on either side of the political conflict. As the process gradually approached the next level of negotiations – those about inclusiveness of government and political power sharing, Egal broke in on it. He had the clan elders of his Habar Awal sub-clan stop their participation in the process and offered political posts and spoils to Habar Yunis opposition politicians, who in their turn then disregarded the participation in any political negotiations of their own clans’ elders. In order to formalise and consolidate the result of these negotiations, Egal had his Guurti organised a clan conference at the Somaliland capital Hargeysa, modelled after the one in Boorama. It was nothing like it, how- ever. The conference was carefully engineered and fully under the control of the power circle around the president, now including his previous Habar Yunis opposition figureheads. Delegates of the different clans were hand picked in order to deliver the desired outcome, a new government as preconceived by Egal and his former competitors. From then on it was the govern- ment, not clan elders or politically active elders who regulated clan representation (SAPD 2002; interviews Ali Dirriye Jama ‘Mudubbe’ 06.04.03; Abdil- lahi Mohamed Ahmed ‘Filter’ 07.04.03; Suleiman Awood Jama 06.04.03).

Moreover, the 1997 Hargeysa conference signalled the end of clan-based representation in the Houses of Parliament. It was decided to introduce – in due course – a multi-party system. The idea as such was generally accepted among urban populations, politicians, civil servants and intellectuals. How- ever useful the clan-based representation system had been immediately after state collapse, and however commendable the role of the clan elders, the ‘traditional’ system was not suited to deliver proper governance and development. The elders could keep or make peace in case of conflict, but their role remained short of the level of leadership and administration needed to make laws and enforce them, to make policy or to provide services to the population such as health and education. This was what was expected of the state, not only by the educated elite, but also by the population at large11. (The state was supposed to provide.) Last but not least: the only instance in which Somaliland would stand a chance of winning international recognition (and international financial aid) would be if it presented itself as a modern state with a democratic system of government. Egal sensed this very well. Surfing on the nationalist sentiment and the popular concern for international recognition, he expanded the realm of the state-moving to bring local governance and taxation controlled by the clan elders under government control. At the same time, some tasks which are generally considered as crucial attributes of statehood remained ‘outsourced’ to the clan elders outside the state realm.

Drawing and shifting borders

After the Somali state’s collapse in 1991, elders in various regions started to develop initiatives in the sphere of governance and service provision. In Boorama for example a so-called ‘social committee of elders’ dealt with local governance issues. It helped in the administration of the town and the sur- rounding areas, overseeing peacekeeping as well as local development. In conjunction with local businessmen, administrators, intellectuals and local professionals, it determined development priorities for the region and regulated relations with external interveners, such as international NGOs. The relatively safe and regulated environment provided by what Menkhaus has called the ‘civic coalition’ resulted in enthusiastic participation on the part of the international NGOs, which kept expanding their activities in the region (Menkhaus 1997 : 35). After the installation of a Mayor and the governor in Boorama in 1993, the social committee of elders functioned as a semi-official city-council to the mayor. Following the 1997 Hargeysa conference, however, this changed. The central government blocked the elders’ initiatives and made it clear to all concerned that it was the state administration that was the relevant authority to deal with. The international agencies were requested to shift their offices to Hargeysa or to face expulsion. In addition to the offices, the Boorama regional economy lost local jobs and other benefits as well as the leverage to generate its own income and to determine its own spending priorities12. Moreover, as from 2000, Hargeysa curbed taxation by municipal authorities, increasing Boorama’s (as well as other municipalities’) financial dependence on the central government13. Local authorities appointed by the central government stopped soliciting the advice of the social committee, which lost its leverage and eventually disappeared.

In the sphere of public order however, it appeared evident that neither the government, nor the administration, nor the police or any other state institution was in control. The state (embodied by its institutions and officials) did not have the monopoly over legitimate violence. It was unable to maintain public order without the help of the local clan elders on the ground and had to depend on local security arrangements. In Bur’o, for example, the po- lice force left disputes between local clansmen to a body of elders called the ‘Peace Committee’. It settled disputes according to heer and functioned on an ad-hoc basis without fixed membership or a set number of members. It was composed in accordance with the specific needs of each particular case. As for its status, I was told that the Peace Committee was a ‘tribal’ institution,

which was recognised by the government. Moreover, the Regional Governor often seems to have been part of it as one of the elders14. The role of the po- lice was apparently limited to assisting the elders involved in resolving the conflict. Moreover, ‘formal’ state institutions involved in law enforcement as such functioned in a particular way. At Bur’o municipality a set of officials including the local police commander and the commander of the local custodian corps explained their role to me as follows. Allegedly, theft and other petty crimes were, in principle, handled by the police and the lower courts of Somaliland’s formal justice system. A murder case, however, was automatically a matter for the elders of the involved parties. According to the officials, murderers were caught by the police, sent down to court, convicted and jailed. Then, the government called the families to negotiate. When an agreement was reached, blood money was paid and the sentence was ‘reduced’, referring to the fact that the perpetrator was in fact released15. The impact of the elders (and of Somali ‘traditional’ law, heer), however, ex- tended far beyond murder cases. It appears that settlements were reached out of court in most instances involving conflicts between civilians such as land issues, theft or assault. Reportedly, the formal justice system was compelled to condone or even ratify any decision taken by the elders for fear of (otherwise) triggering uncontrollable violence, thus undermining the existing fragile stability (SAPD 2002b). Even relations and conflicts between state agents acting in their official capacity and civilians – for example when a policeman shot someone in the context of a police operation – were subject to heer.

The apparently complete overlap of the activities of formal and informal agents in the sphere of public order, and the fact that conflicts were processed via the ‘traditional’ system, however, did not hinder the shift of real political control from elders to the political class. On the contrary, outsourcing security was functional and served the purposes of those in control of the state apparatus. Rather than limiting their leverage, it expanded it even further. (In a context where the political and military balance between clans [as well as the perception of that balance] is very important and has a potential impact on the national political level, the political stakes in a conflict can be- come very high.) Government agents and officials were in a position to take part in informal ‘traditional’ proceedings as elders. At the same time how- ever, they were still government agents with a position they owed to the political patrons who appointed them. By means of the resulting loyalties the political patrons exercised control over the process. In other words, in cases where the political stakes were high, there was a form of direct political control, exercised by the political actors who controlled the state apparatus, al- lowed by the elusive borders between the ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ sphere.

The more centralised, the less participatory Somaliland became. The government, controlled by the president, increased its leverage and political power to the detriment of decentralised, governance structures and proc- esses steered by informal leaders and institutions associated with the clan system. To be sure, clan and clan leaders/power brokers remained highly relevant. The increased economic leverage allowed the government to further expand its control by expanding the scope of patronage and clientelism. President Egal masterfully played the strategic game of giving and taking spoils and benefits to clan powerbrokers in the capital Hargeysa and the regions, while maintaining the power balance between them and keeping them loyal to him. The centre of power of the Somaliland heartland was Hargeysa. Despite the persistence of clan politics, the relevant players were now not the clan elders but the politicians.

This trend was continued after 2001, when the constitutional referendum abolished the clan-representation system and introduced the multi- party system and universal suffrage. The constitution had won overwhelming approval, yet, as pointed out by ICG (2003), it was held in the midst of a popular Somaliland nationalist frenzy and the approval rates were mainly due to article 1 of the draft, which re-affirmed the Somaliland independence. It was a matter of controversy, however, that the number of political parties to be registered under the multi-party system was limited to three, a measure proposed in order to prevent parties from drawing exclusive support from particular ‘tribal’ (clan) or religious constituencies. Egal died before the first actual election (on the municipal level), which was held in the autumn of 2002 and won by the government party UDUB. Meanwhile Egal had been succeeded by his Gadabuursi vice-president Dahir Rayaale Kahin who subsequently successfully contested the 2003 presidential election at the head of that same government party. The presidential election had been considered reasonably free and fair by domestic as well as foreign observers (Lindeman, B./Hansen, S.J. 2003). Yet, Kahin, a former high-ranking officer in Siyyad Barre’s National Security Service (NSS), promptly started recruiting former NSS colleagues as his advisors and in lower ranking administrative functions. Soon, the president was accused of displaying disrespect for due process and for the Somaliland constitution, organising and expanding his own secret ser- vice outside any legal framework and beyond public oversight (ICG 2003 : 33).

Kahin continued to rely on the government clique’s patronage network which extended far into the social fabric of Somaliland’s ‘traditional’ clan structure. However, the coercive power of the government became ever more tangible. While under Egal the government had to tread carefully when taking on its political adversaries, for fear of antagonising their clan constituencies, under Kahin political arrests became possible. In January 2007 three journalists of Haatuf/Somaliland Times Newspaper were arrested without warrant and detained incommunicado in prison. Reportedly, the reason for their arrest was Haatuf’s publication of a series of articles alleging corruption on the part of the president as well as his wife Huda Barkhad.16 They were tried under the old Somali Penal Code and convicted to two years and five months imprisonment plus a fine for ‘reporting false information about the government, discrediting the President and his family and creating inter- communal tension’. All local and international protests were of no avail. The men were only released after a presidential pardon, implying that they remained guilty (Afrol 29.03.2007)17. Four days before the presidential pardon for the journalists, according to a report of the Somaliland National Human Rights Network, security forces cracked down on a protest of meat traders in Bur’o who were demonstrating against a doubling of the city’s abattoir fees. Armed police stormed the building and arrested the protesters. The same day, they were sentenced to six months in jail by the regional security committee, an extra-legal body controlled by the president’s security service. The number of reports of similar incidents is increasing steadily. At the time of writing this article, September 2007, the Hargeysa Regional Court had convicted three prominent Somaliland politicians (including one of Rayaale’s former ministers) to a prison sentence of three years and nine months for il- legally forming a political party, engaging in unauthorized political activities and putting the good name of the head of state in disrepute (Somaliland Times 270, 24.03.2007).

While under Egal the Guurti still had sufficient leverage left to mediate in instances of conflict between the government and its opposition, this is less the case today. As the ‘upper house’ of the bi-cameral parliament, the Guurti’s status was an issue of debate when the multi-party system was introduced. As a house of clan elders, it could hardly be subject to a popular election by universal suffrage. Or could it? The 2005 parliamentary election proceeded without tackling that thorny question, which the Guurti members in fact refused to discuss or consider. As a result the parliamentary election only regarded the lower house, the House of Representatives. Thus by at- tempting to extend its own shelf life, the Guurti considerably undermined its own standing as the ‘unique institution that had been at the heart of clan-based power-sharing and consensual politics in Somaliland, linking modern political institutions to traditional political organization and, by extension, inter-communal poli- tics to national politics’ (Kibble 2006).

President Rayaale has unilaterally (and illegally) extended the Guurti’s man- date in March 2006 (Kibble, S./Abokor, A. 2007). Since the parliamentary election, overt criticism levelled at the current political class is mounting. Government and opposition politicians are increasingly mistrusted as mutu- ally interchangeable, self-serving, corrupt and unscrupulously using clan politics to achieve their goals. The use of clan politics affects relations be- tween the communities belonging to those different clans inside as well as outside the capital Hargeysa. It is bound to affect – in some way or another – the capacity of local clan elders to make and keep peace as well. The containment of political competition is no longer the business of the clan elders or the Guurti. Interestingly, in a number of cases that role seems to have been duly assumed by prominent members of Hargeysa’s civil society (e.g. members of think tanks and NGOs or individual intellectuals and religious leaders) forming ad-hoc committees mediating between the concerned stake- holders in a political conflict18. It is they who now seem to represent Somali- land’s hope for peace as well as governmental legitimacy and accountability.

Conclusion

Looking at Somaliland one cannot help being amazed by the dynamics and the complexity of the coming into being of this polity. Somaliland is the result of a political process extending beyond its 17-year-old existence. In that political process, setting or shifting borders between formal and informal spheres has been an instrument in the struggle for political power and control. What has happened? ‘Traditional’ clan leaders and institutions provided the necessary political and institutional bypass to allow Northwestern politicians and strong-holders from the former regime to establish or re-establish control as governors and administrators of a new polity while enjoying the necessary legitimacy and resources to that effect. The claim to formal state- hood, allowed these politicians to eventually push community leaders (clan elders), who had done their share in building the polity in the first place, from the ‘negotiation table’, while keeping their assistance at hand for tasks strongly associated with state monopolies, for example, maintenance of pub- lic order.

Somaliland nationalism, born in the civil war against Siyyad Barre, was real. The local conviction that Somaliland was a state and that it should be recognized as such was real. It helped sustain legitimise President Egal’s claim on selected typical attributes of statehood such as the establishment of government institutions and agencies, taxation (however symbolical) or a national currency. Control over these selected attributes allowed Egal to recapture the pivotal place in politics. The Somaliland clan elders were (out of necessity) allowed to borrow from SNM politicians during and just after the war with Siyyad Barre. Egal successfully manipulated notions of the formal and the informal to bring the elders back under control, thus consolidating his position. Egal’s successor Rayaale completed the process. Many North- western pre-civil war politicians, who had made a career in Mogadishu, are back in power – albeit on a smaller turf than before.

In conclusion: what is the contribution of the factor ‘traditional’ institutions to state-building? Do they guarantee more legitimate, accountable and effective governance? It is not quite as simple as that. The Somaliland experience seems a far cry from the somewhat romantic idea of simply instumentalising informal traditional institutions as a kind of ‘appropriate governance technology’ solution for problematic statehood in Africa. In fact, Somaliland, as a result of a process involving ‘traditional’ leadership and institutions, could be considered as a (case of successful reconstruction of political arrangements amounting to a) neo-patrimonial system in the sense of Chabal and Daloz (1999). So, are informal institutions indeed detrimental to legitimate, accountable and effective governance? Are they indeed contributing to state failure rather than repairing it? As Meagher (2006) observed, it would be misguided to attribute political outcomes to assumed inherent characteristics of African society, politics or culture – as if it would be impossible per se for Somali political actors to foster some form of functional and equitable governance. It is not. that Somaliland as it exists today is the result of a political process involving competition between political actors (from the ‘mod- ern’ as well as ‘traditional’ spheres) who have operationalised and instumentalised notions of the formal and the informal or the ‘modern’ and the ‘traditional’ in that process. Taking this into account, as an external actor one cannot avoid the ‘political’ by invoking the ‘traditional’. State building is a political process. At the same time, one cannot invoke the ‘traditional’ to ex- plain the ‘political’. The destiny of the Somaliland polity is not predisposed. ‘Informal’ or ‘traditional’ institutions are not inherently good or bad for political legitimacy, governance or the degree of popular participation in it. Progressive powers in Somaliland will have to take it from here, working for more legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness of government through and perhaps beyond the institutions currently at their disposal, be they for- mal or informal.

By Marleen Renders