Somaliland Oil Economy

Somaliland:

An Early Warning to Manage the Politics of “Oil Economy” and Opportunities to learn from the Available Wealth of Global Experience.

- Background

After independence, the Somaliland people did not inherit any significant development infrastructure or any other economic sectors from the colonial rule. The colonial authorities found them as nomads and left them still predominantly nomadic, because they needed their product raw and undeveloped – meat. The Somaliland economy has always been meat-rich and still is. Obviously, the livestock imports were useful for them on the hoof, to be slaughtered fresh in Aden, the major base of the British forces in the region, and subsequently in the oil-rich Gulf countries.

The oil exploited in Arabia could have also been found in the Somali region of the Horn of Africa. It has always been strongly rumoured that black gold is also abundant in the Somali inhabited region and of both on-shore and offshore nature. However, it remained to be a hush-hush business and has never been exploited. Why is the international system so unfair to the Somalis to leave them languishing in poverty? The answer often lies with their indigenous governance institutions, I would argue, which are totally incompatible with the dominant Christian-based Western model. But that was also true of the Arabian Peninsula, whose dominant culture is both ethnic and Islam based. But the difference is the development of a hierarchical society where the rule comes from one source; in the Arabian context the “Sheikh”, which for the Westerner is tantamount to a kingdom model of governance. On the contrary, the Somali model is diffuse, with no single ruler to deal with, but is often so fragmented and ad hoc in nature. Therefore, the colonial authorities had to create their own system to control the population, which was never in sync with the local culture and beat.

In the same token, the oil companies, at the time, needed to have a stable authority to deal with in order to have guarantees for the long-term recovery of their huge investments on the exploration and exploitation of the oil resources. It is obvious, Somalis could not fulfil that condition, and hence the oil industry decided not to waste time on the unruly Somalis and let the development of the oil economy by-pass them. However, today, things are changing; the world’s energy needs are growing exponentially, and the traditional sources are either depleting or no longer as stable as they used to be. The African oil potential, especially the Horn region, is coming into the radar again. Nevertheless, the question still stands whether Somaliland is fulfilling the basic condition of stability and by extension whether the oil industry is ready to commit this time to exploit the Somaliland oil. It is also important to raise here in this context, the reality that most of the societies of resource-rich countries did not benefit from windfall incomes of their black gold and other mineral resources, but rather has gotten more impoverished and socially stratified. So, will Somaliland be able to avoid the pitfalls of the other Sub-Saharan Africa countries, the resource curse, and ensure that its population at last reaps the benefits of its natural wealth?

- What is the Resource Curse?

The Somaliland Minster of Water and Mineral Resources, answering a question of what Somaliland is doing about possibility of resource curse impact is on the record that ‘He would rather have the resource curse in the present circumstance.”31 This could be an indication that the Somaliland Government has no clue of the dangers involved in becoming an oil producing country and hasn’t made any serious thought and planning on how to handle the possible windfall earnings accruing from it. It is, though, understandable that it is in a desperate economic situation to provide services to its people, but it is forsaking the fundamental responsibility of any government to bring to the public its vision and strategies to utilize the natural resources and endowments of the nation for the benefit of all and not for the few in the seats of power to line their pockets.

The term resource curse mainly applies to the sub-Saharan African countries which although resource rich, failed to transform their earnings into development and improvement of their people’s standards of living (Carmignani and Chowdhury). There are three main reasons why huge revenues from oil could become a curse to a country (Ghazvinian, 2007): first, oil revenues inflatethe value of a country’s currency, hence making its exports more expense and less competitive in the international markets. Furthermore, the national labour force flocks to the oil sector and that weakens the traditional sectors of the economy especially the agricultural sector, which makesthe country import dependent, a situation usually termed as the “Dutch Disease”. Secondly, it corrupts politicians, because the Government is not dependent on taxation but rather on oil income and hence is less accountable to the people. Moreover, the economy is more under the mercy of oil price fluctuation rather than being engineered by the Government. Thirdly the oil sector is a capital-intensive industry and not labour-intensive and therefore, often imports its skilled people from outside. Local people are usually hired as security guards and drivers and not much more(ibid).

It is argued in the literature that so far, oil companies and governments in developing countries have followed a specific model of development where oil companies produce oil (and gas) for export, and host governments get a hefty share of the profit in the form of taxes and payments. From there it is the job of host Government to make the effort to promote employment and supply chain opportunities at the local level (Shankleman, 2013). Shankleman further argues that a structural industry problem is that oil companies face issues of currency, costs and capabilities: they have to employ skilled people from international market and should pay them in US dollars; they have to recover their huge investments through exports to the energy hungry international markets and not to supply local markets33; and that they are not in the business of local development to create jobs, but rather specialize in oil production, its marketing and therefore generation of huge revenues. This economic model is where the irony of “plenty and poverty” in the resource industry is observed. “Where this model applies in West Africa, it is typical to find huge, state-of-the-art oil and gas export facilities sitting alongside communities where people live in houses without electricity.”(Shankleman, 2013)

Furthermore, as KatjaHujo (209) argues, the literature supporting the resource curse thesis is based on the following arguments.

- There is supposed to be a long-term decline in terms of trade for commodities vis-à- vis manufactured goods (the famous Prebisch- Singer thesis).

- Dependence on mineral rents creates revenue volatility because of unstable prices in world markets, which is detrimental for investment and public finance.

- The enclave nature of mineral-based industries has few linkages with the rest of the economy and provides little direct benefit to local communities.

- The macroeconomic effects of foreign-exchange inflows (‘Dutch disease effect’) can have detrimental effects on competitiveness, balance of payments and debt, and eventually crowd out investment in sectors with higher value-added skill requirements and labor demand.

- Resource abundance is frequently accompanied by an increasing role of the state, which (especially, but not exclusively, from a neo-liberal point of view) can produce further problems associated with ‘government failure’: bad decision- making, corruption, rent seeking, protectionist policies, inefficiency and market distortions.

- Resource wealth influences the nature of political regimes, which tend to be classified as rentier states, developmental or predatory regimes; the nature of the regime has implications on institutional capacity, quality of the bureaucracy and its relationship with the natural resource sector.

- The Botswana Model of Development on How to Avoid the Resource Curse

Where the rest of resource-rich African countries failed, Botswana succeeded to avoid the pitfalls of resource curse to manage its diamond economy. Its successes lie in a three- pronged approach strategy (Paula XimenaMeijia& Vincent Castel; 2012):

- Economic diversification to protect itself from the volatility of the mining sector

- Sustainable Fiscal Policy – It delinked its expenditure from its revenues

- It invested surplus revenues for future generations

In the Botswana case,“the state recognized that mineral wealth, or the country’s “inherited wealth”, was limited in that the wealth acquired from mining would only last as long as there were diamonds

To be found. “Created wealth” on the other hand could provide the country with an answer to its objective of achieving long-term sustainable development.” (Paul et al, 2012). Botswana followed the above three approaches in its strategic economic development.

- In its economic diversification policy, Botswana promoted the manufacturing sector; especially the meat products35, and it established institutions and economic infrastructure to promote private competitiveness as the engine of its diversification strategy. Key among its strategies to promote economic diversification is the creation of the Business and Economic Advisory Council (BEAC) in 2005. The council mandate includes identifying constraints hindering economic diversification and formulating key strategies and action plans to overcome those constraints.

- In the implementation of its Sustainable Fiscal Policy, and delinking of expenditure from revenue, it pursued a six-year National Development Plan integrated with the Annual Budgetary Process to ensure the establishment of an efficient economic management process. “Beyond the considerations taken into account in the drafting of the National Development Plans, their oversight, structure and recurrent nature are also a fundamental source of Botswana’s successful wealth planning track record”(ibid). Further steps to ensure the integrity of its National Plans also include that no change can be made to the plan without Parliamentary approval and that scheduled term reviews of the plan are held.

- Botswana invests its resource income. In its investment strategy, Botswana has established the Pula Fund, which has two functions: a) it is a stabilization fund to finance Government fiscal deficits and b) a savings fund for future generations. The investment strategy is also used in the development of productive sectors of the economy to offset the “enclave” nature of the resource economy and in the promotion of the private sector efficiency as a vehicle of the diversification programme.

- Good governance as a prerequisite for sustainable wealth management also contributes to Botswana success: a legitimate and accountable Government fostered long- term decision making, an integrated and vocal civil society encouraged broad consensus in formulating economic policy, and putting anticorruption policies in place allowed for the transparent distribution of resource benefits (ibid).

- Community Relations and Oil Companies

The oil industry is a conglomerate business, which in its governance and management systems is far removed from community level dealings. However, as a matter of necessity, the oil industry has covered a good distance now to open a window for the accommodation of the local community needs and demands. Some of the ways that oil companies interact and support local communities are outlined below, with the example of Uganda (Tower Resources, Local Matters).

- Building Community Awareness of the Company and Oil Industry in General: building an information centre to provide company promotional material including calendars and oil books support to educational institutions.

- Communicating with local communities to keep them informed of the activities of the company in the area at its different operational stages. Some of the methods employed are: town hall meetings, school presentations, radio phone-ins, and open air meetings in markets and religious venues.

- Maximize employment and training benefits of the local population in the company. It is also important commitment to develop local content participations in the country’s oil industry at the national level.

- Continuous consultations to gain feedback and understand community priorities for social investments and to design relevant projects for all citizens. Companies also need to make consultations with agents of both local and central governments to ensure compliance with national priorities.

- Is Somaliland Learning from the Experience of other African Countries?

Somaliland has an opportunity to avoid the pitfalls of most African countries that relied on the windfall earnings from resources, especially hydrocarbons. It is now in the entry stage of oil exploration, which affords it time to prepare its governance systems and its communities for the challenges of being an oil producing country. It should start to undertake a contextual analysis of Somaliland’s socio-economic and political situation and then base its strategies for development on the outcomes off this analysis.

Somaliland’s economy is mainly reliant on the livestock sector, which provides direct or indirect employment to no less than 70-80% of the population. It sustains over 60% of the population with pastoralist and agro-pastoralists occupations. It also sustains another 20% through the export of livestock on the hoof, the local slaughter business, and the sales of its other products such as local milk consumption and exports of hides and skins. A junk of the remaining population works in retail Khat business and other miscellaneous occupations such as commerce, public and modern private sector employment, and on remittances. Somaliland needs to have a strategy and planning system for how the advent of the hydrocarbon age in Somaliland will affect these employment sectors. It is also important to analyse how the fragile governance institutions will behave in a situation of slush funds and windfall oil revenues, without robust regulatory and public governance mechanisms, and how to counter its corruptive effects. A further caveat will be the fact that Somaliland lacks international recognition and how that will affect its capacity to manage its wealth.

Somaliland faced difficulties from the start to attract interest from international oil companies for the exploration of its hydrocarbon potential, because of its unrecognized status and perhaps because of pending claims from concessions allocated by the deposed Somalia Government. There was only one unallocated concession area and that was the so- called Odweine zone or Block No 26. Subsequent governments in Somaliland tried to tap into that huge potential to break the shackles of the undeclared international economic embargo which result in its inability to adequately provide for its people. However, recently, it looks like the tide is turning and Somaliland may have its day.

Despite the constraints imposed by Somaliland’s unrecognized status, there are several companies which acquired concessions from different Somaliland Governments36, chief among them, Genel Energy, the largest oil firm in Turkey, now headed by the former CEO of BP, Tony Hayward, which is the company that succeeded to discover oil in Kurdistan and is now prospecting in two key areas of Somaliland: 1. It is leading the Odweine block in partnership with Jacka Resources, Australian based explorer and the Petrosoma Ltd, owned by the Somaliland-born UK citizen investor based in London. 2. Genel Energy is also operating a concession in eastern Togdheer and Saraar regions in partnership with East Africa Resource Group. Other companies who are holding prospective concessions are the Ophir Energy, London based explorer that will operate two blocks near Berbera and the

Early Warning Signs

The recent developments in Genel Energy operation areas of eastern Togdheer and Saraar, show lack of preparation and attention to the communication with the local communities in these areas. The communities in those areas, especially in the Saraar region, have been complaining about several issues: First, the traditional leaders of these communities as well their elected politicians were unanimous that they were never made serious partners of on the ground work and preparations for the oil company to start its survey operations. Secondly, the local community on their part complained that they were not given due consideration when recruiting local staff for the company. As a result, the company planes conducting aerial surveys were shot at and had to suspend the survey. Although, nothing of the sort happened in the Odweine side and the aerial survey has been completed, still the Company has suspended its operations for two months, hoping that the authorities will sort out the problems of east of Burao blocks.

The above crisis is happening at an early stage of Somaliland’s oil exploration operations and should be viewed as an early warning to the Government and to the society at large for a serious lack of understanding and preparation for the dynamics of the oil economy and politics. If the oil sector is managed in the usual practice of disorganized, clan-based traditional fashion, it is has the potential to destabilize Somaliland and prove to be a real curse. Somaliland state has several weaknesses which makes it vulnerable to the vagaries of oil economy: a) Its central government institutions are not strong enough to adequately enforce the public ownership nature of the resource wealth and guarantee the smooth running of the operations of their exploitation, b) there is a general lack of experience, coordination, and public information in dealing with oil companies. However, despite these shortcomings, there is a general public understanding that without oil income, Somaliland has limited opportunities of overcoming the grinding poverty, which its people are subjected to and the economic challenges facing their statehood aspirations without such a breakthrough. However, such popular spirit can only be tapped into through accountable and legitimate governance and definitely the current rent- seeking behavior, which is now identified with the oil sector management, is not helping that aspiration.

Way Forward:

“Resource wealth influences the nature of political regimes, which tend to be classified as rentier states, developmental or predatory regimes; the nature of the regime has implications on institutional capacity, quality of the bureaucracy and its relationship with the natural resource sector”. Katja Hujo

- National mining and hydrocarbon laws have to be in place before any serious oil work and contracting starts. These laws are not now there, and obviously the companies are operating in a legal vacuum, possibly on the basis of the defunct Somalia state laws.

- The local contracting must be transparent and accessible for both the media and oversight institutions; such contracting include the field logistics work such as catering, transport, security, and other locally manageable works. Similarly the disbursements of ‘social funds’ should also be transparent and nationally accessible.

- In view of Somaliland public institutions weaknesses, the Somaliland Government needs to maximize the strong culture of dialogue and consensus building to compensate the deficiencies in the state authority reach. That approach has served Somaliland well for maintaining its peace and stability and should do so also in the sound management of its natural resources.

- The hydrocarbon resources should remain a national wealth, but in meantime should benefit the local population, which would sacrifice some of its traditional livelihood assets such as pasturelands. The state, in conjunction with the local authorities both modern and traditional as well as the oil companies should be able to carefully keep all key stakeholders and actors on board. The state should be the lead agent of this process.

- The social development components need to focus on the priority needs of the local communities, which would have a longer-term impact of alleviating poverty such as provision of basic social services and business investment initiatives and infrastructure to open economic opportunities.

- It is important to establish conflict resolution mechanisms at the local level, so as to avoid problems blowing out of proportions when not addressed at the grass-root level on time.

- It is important that the Government should factor in the African negative experience of single resource dependence and should seek appropriate resolution for Somaliland to avoid the pitfalls of the “Resource Curse”. It needs to start an in-depth analysis of the possible trajectory of the impact of oil revenue to the traditional sectors of Somaliland’s economy and the aspirations for a sustainable, just development of Somaliland.

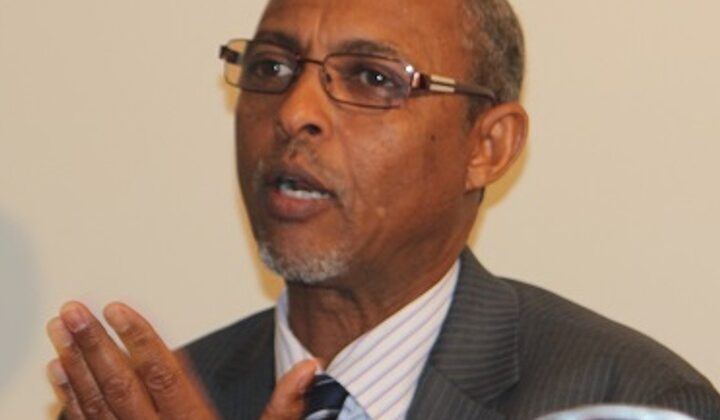

By Dr. Mohamed Fadal