Somaliland Seed

Somaliland Seed

- Introduction

The Development Fund-Norway conducted a rapid assessment to identify needs and challenges associated with seed security among rural communities in Somaliland. The purpose of the assessment is to provide field-based information for the implementation of community seed banks in Somaliland. The report contains main findings from fieldwork and concrete recommendations in relation to the type of CSB, services and associated costs; as well as, in relation to capacity-building needed among farmers and partners for an effective implementation of CSB in Somaliland.

- Area and scope of the study

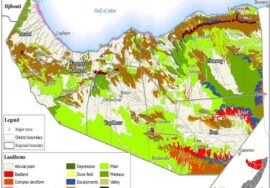

The rapid assessment is based on focus groups discussions carried-out in five different communities in Somaliland. Selected communities are those with on-going projects, implemented by Development Fund´s partners in Somaliland. The information is, therefore, relevant for Lafta Thinka in Gabiley district, Dubur in Sheik district; Beerato and Haahe from Odweyne district. However, seed security situation in Somaliland is similar for most of the farmers according to agricultural officials from Somaliland. So, although the assessment is based in few communities, it is expected to give a representative picture of seed security situation of Somaliland farmers in general (Map 1).

Focus groups discussions were used to gather information from farmers, women cooperatives and local Village representatives. During focus group discussion, four-cell analysis1 was applied in order to gather information on relevance and distribution of key crops and varieties of key food crops in selected communities. Interviews were carried out with key informants form the government and FAO. Development Fund partners in Somaliland also participated in generating information and facilitating field visits. A complete list of interviewed people appears in Annex 1.

- Agriculture in Somaliland

One of main agricultural zones in Somaliland is located in the North-western part of Awdal and Gabiley districts2. However, farmers are also cultivating in Odweyne, Burao and Berbera district along Somaliland; most of them depending on irrigation systems. Gabiley and Awdal are the main areas for rain-fed production. The agricultural systems in all villages are a combination of maize and sorghum with cash crops (fruits and vegetables) and livestock herding (camels and sheep). One of the main cash crop in Somaliland is watermelon. All villages visited were harvesting it since it was the end of the rainy season (“Gu Season”). Farmers also produce various vegetables, such us tomatoes, onions, paprika, green chillies, potatoes, okra, parsley, which are minor cash crops sold in local markets (table 1 below). Crop production in Somaliland is determined by bi-modal rainfall. In most of the villages land is mainly communal (70%) vs 30% private. The process of privatization of land is accelerating in recent years (Ministry of Agriculture and partners, personal communications).

The two main agricultural seasons in Somaliland are: Gu (rainy season) from April to June and Dayr (Autumn) from September to October-November; the amount of rain during Dayr is not good enough; most farmers need irrigation during Dayr Season. Summer time or Xagaa Season is from June-July and Jiilaal “ dry winter season” from December to March. Jiilaal is the hardest Season of the year. Therefore, it is recognised as the season of uncertainty and desperation for many Somalis; while Gu is considered the season of abundance of milk, meat and good crops.

Drought periods are getting more severe and the majority of farmers are relying in irrigation and water harvesting systems to cope with erratic rains. Many donors, such us The World Bank, FAO, IFAD and many International NGOs are working with water management systems. Development Fund´s water management projects in Somaliland are allowing farmers to have access to irrigation systems during dry seasons, especially during Dayr (Autumn).

- Food and cash crops in selected communities

All communities we visited cultivate maize and sorghum as main food crops; while watermelon, tomatoes, onions, green chillies and hot pepper are main cash crops. Fruits such as papaya, mango, guava and lemon are also good sources of income and food for villagers. Seeds of maize and sorghum, in some case cowpea as well as some fruits are found locally. However, seeds for most crops are imported (table 1). Watermelon is imported and there is only one variety produced by most farmers in Somaliland.

In terms of maize and sorghum there are few landraces still conserved by farmers.

Storage systems are similar in most communities: seeds “grains” are conserved with dry cow dung and hang in sacks inside the house; in some cases seeds are treated with salt and ash and hang in sacks inside the houses.

The challenge is to find enough space inside their homes to hang enough quantities of seeds. In the case of Lafta Thinka grains are conserved in underground pits. Loses in terms of grains are very feasible: insects attack the storages and heavy rains can infiltrate water in underground pits

- Mapping diversity of local landraces

A four-cell analysis was conducted to identify which varieties are cultivated by majority of households and in large areas. Maize, Sorghum and watermelon are cultivated by many households and in large areas (cowpea in some cases). However, there is only one type of watermelon, and seeds are imported. Maize and sorghum seeds are maintained by farmers. Therefore, a more detailed four-cell analysis was carried out to identify diversity of local landraces of sorghum and maize in all communities.

5.1 Sorghum and maize varieties in Lafta Thinka community

Lafta Tinka is an agriculture village of 637 households, located 10 km south from Gabiley downtown (more information in annex 2) and maize are produced in large areas and by many households.

Maize varieties: Lafta Thinka farmers grow five different maize varieties: Nijaar (white maize), Lowso (yellow maize), Cadey, Sankab (short nose) and Sandheer (long nose). Both Sankab and Sandheer are maize landraces3 derived from Cadey variety.

Nijaar “white maize landrace”, and Lowso (Yellow maize) are cultivated in large areas and by many households. The rest are cultivated by few households and in small areas.

Cadey, Snakab and Sandheer have small areas and few households; are drought tolerant, have long stalk, give high fodder production. Cadey, Sankab and Sandheer mature in a 4 months period. Nijaar: has very good taste and short maturing

(matures in 3 months time). Both Nijaar and Lowso produce more yields per ha than the other three (Figure 2).

Sorghum varieties: sorghum is a very important food crop among Somaliland communities.

Lafta Thinka farmers have 6 varieties of sorghum: Elmi Jama and Adam Gaab (produced in large areas and by many households); Carabi is produced by few farmers but in large area, while Masago, Caqli Badan and Karmiici are produced by few households and in small areas.

5.1 Maize and sorghum landraces in Dubur village Dubur is a community of 500 households, located in Sheikh district in the North-western Togdheer region of Somaliland (more information in annex 3).

Dubur is also involved in a farming system combining sorghum and maize as food security crops with vegetables and fruits as part of cash crops. Figure 3. shows maize and sorghum are cultivated in large areas and by many households. There are only two maize landraces under cultivation in Dubur village: Adhiyo (yellow maize) and Galbedi (white)

Sorghum is an important crop in Dubur; 8 local landraces of sorghum are cultivated: 1 Galbedi, 2 Yallaxle, 3 Elmi Jamal, 3 Baydhabawi, 4 Masango, 5 Yallade, 6 Qalaafo, 7 Finjis, and 8 Dhagahabur. Masango and Baydhabawi varieties are grown by many households and in large areas, the rest of varieties are produced by few households and in small areas, which means that Dubur has a challenge in maintaining these varieties in the long run. One strategy may be to encourage cultivation and testing adaptability properties of those varieties used by few households. Some may have better drought tolerance traits for example; few farmers argued it was the reason why they continue cultivating those varieties (1, 2,3, 6,7,8).

5.2 Maize and sorghum landraces in Beerato village

Beerato is a community of 700 households (85% are agro-pastoralists and the rest pure pastoralist). Beerato is located in Odweyne district (more information in annex 4).

20 farmers participated in focus group discussions (7 women and 13 men).

Beerato cultivates only two maize landraces (Adhiyo –white maize – produced by many households and in large areas) and Adheer (yellow maize), which is cultivated by few households and in small areas; maize in large areas is irrigation based. Beerato has the challenge of diversifying maize varieties.

In terms of Sorghum varieties, Beerato has 5 landraces: Masengo and Yuluk which are cultivated by many households and in large areas. While Isgadi, Elmi Jaama and Galbedi are cultivated by few households and in small areas (figure 5).

5.3 Maize and sorghum diversity in Haahi

Haahi is a community with a population of 400 households, located in Odweyne region of Somaliland. 31 farmers participated in focus group discussions (15 female and 16 male).

Haahi cultivates only one maize variety –Adhiyo, which is produced by many households and in large areas. The challenge is to recover other maize varieties and to test its adaptability in Haahi region.

Sorghum diversity is also low; Haahi cultivates three Sorghum landraces: Masengo and Yoloha, which are cultivated by many households and in large areas), while Mara-ato is produced by very few households and in small areas. Haahi has the challenge of diversifying sorghum varieties in the territory. Especially important is to test drought tolerant landraces from other areas in Somaliland or from other countries.

5.4 Mapping maize and sorghum diversity in Doha-Guban

Doha-Guban is a community of 200 households most of them agro- pastoralists. Doha-Guban is located in Berbera district in Somaliland; more information about Doha-Guban in annex 5.

Doha Guban cultivates three maize varieties: Adhiyo is one. Farmers also mentioned the presence of two more white and yellow varieties but without specifying the names. The three maize varieties are cultivated by many households and in large areas. Doha Guban cultivates only one Sorghum variety, named Galbedi.

The challenge in Doha Guban, but also in the rest of communities is to recover both maize and sorghum varieties currently used by few households, spread its use and test adaptability; especially with regards to drought tolerance.

- Seed supply systems for selected communities

Farmers in the villages keep local seeds of maize and sorghum; some villages keep seeds of cowpea and brown beans. For the rest of the crops, seeds are imported from Ethiopia, Kenya and Europe. Farmers buy the seeds in local shops and wholesale markets from Hargeisa, Gabiley, Burao and Berbera.

Seed providers control import and market prices; farmers have no influence on them. There is neither legal framework nor governmental authority monitoring prices and seed quality in Somaliland. During interviews with the Ministry of Agriculture, they argued a Seed Act is very much needed and the new government (4 years old) is starting the process of creating a seed Act for Somaliland. So far, the act is at draft stage and has not yet materialised. It will take some time before it is finalized and can come into effect.

6.1 Challenges with seeds (“Khudrad”) in Somaliland

Dependency on imported seeds: Somaliland farmers are highly dependent on external seed supply systems. Somaliland lacks autonomy in relation to formal (government) or informal (farmers) seed supply systems. However, breaking up dependency from imported and bad quality seeds demands a great effort from government extension systems, NGOs providing assistance to communities and farmers themselves.

Farmers keep local seeds of few food crops (mainly maize and sorghum). Most of farmers in Somaliland are totally dependent on imported seeds for most of the crops produced in the country (table 2). Prices are also reported to be very expensive for some of the imported seeds. However, the majority of farmers buy seeds every year. Previously, they could reproduce the seeds for some of the vegetables/fruits “grains”, nowadays seeds germinate just once and cannot be reused.

Poor quality seeds: there is no quality control for seeds in the Somaliland seed market. Farmers buy seeds without any guarantee. In certain occasions, seeds do not germinate at all or germination rate is very low, then the farmers lose all the money invested in seeds, land preparation and labor (tractor hours, water, etc.) (see box).

Loss of local landraces: local landraces such us the white watermelon disappeared. Local varieties of tomato, cowpea and chilies have disappeared from farmer fields. The reasons are various, but one of them is the introduction of imported seeds, which substitute local ones, and high demand of water in some varieties make those varieties less attractive.

Seed storage: there is significant loss of quality of farm saved seeds during storage. Storage pests are mentioned as serious problem. Another challenge is storage space to keep un-threshed sorghum and maize heads hanged inside the hut, a traditional practice widely used in many areas. In the underground pit (e.g. Sorghum in Gabiley), seed is affected by mould. Therefore, the quantity of seed stored by a household is usually not enough and, hence, they have to depend on markets.

Increase need for local landraces and drought tolerant varieties: crops that may need great amount of water are abandoned (potatoes for example). Farmers argue about the importance of recovering seeds of local landraces and specially those drought tolerant varieties.

Scarce research and extension services on seeds: there is no governmental research related to seeds in Somaliland. Farmers do not have access to technical assistance on seed quality and crop improvement from government systems. FAO Somaliland is trying to strengthen the capacity of governmental extension services in relation to seeds (interview with Dario-FAO, Hargeisa June 2014). Farmers utilize grains as seeds, so there is no systematic seed quality control among farmer informal seed systems (Idem). However, it will take some time in order to reestablish effective governmental extension services in Somaliland.

- Stakeholders analysis

Different organizational structures are already present in the communities:

- Village development Committees (VDC), are organized through sub-committees responding to clusters at village level; clusters are corresponding with different sub-clans living in the different districts. VDC are also dealing with Clan Issues in the villages. There are also different sub committees: health, environmental, and education.

- Women’s associations: DF partners in the communities organized these.

- Farmer cooperatives: they are present in all communities visited. Farmer cooperatives are also organized by NGOs. In this case DF partners.

Most of women and farmer cooperatives and associations are quite new (3 to 2 years old). The organizational constituency of these groups is still weak and needs close follow-up from DF partners during the coming years in order to reach sustainability.

- Model Community Seed Bank for Somaliland

Why a community seed bank in Somaliland? Ownership, seed security and quality of seeds in Somaliland are not guaranteed. Most farmers are depending on external seeds, which become more expensive and its quality is poor. .Most farmers use seeds, which if they do germinate, they do it only once. Seeds are lost because storage facilities are neither appropriate nor sufficient to keep seeds for next season. Securing quality and availability of seeds for farmers is the main reason to piloting a community seed bank in Somaliland.

The question is what kind of CSB becomes the appropriate model? DF´s pilot community seed bank in Somaliland will be a short-term storage system; a dynamic community-based system always linked to local needs and farmer fields. Some of its services will be the following:

8.1 Type of services

- Supplying adequate quantity and quality Seeds: should be kept in enough quantities in order to satisfy local demand of seeds of main food crops. Seeds kept will be those adapted to locality and have good viability.

- Restoration and adoption of drought tolerant seeds: the second function of the seed banks is to promote restoration and introduction of lost landraces of main food crops (sorghum and maize) but also for Curcubitaceas (watermelon, melon, pumpkins) chillies, tomato and other food and cash crops.

- Capacity building: the CSB is also a capacity-building arena for farmers in the community, but also for other communities, that might be interested.

- Create awareness on diversity present in the community. For this a small part of the CSB should keep an exhibition of seeds, which are constantly renovated.

8.2 Infrastructure needs

The CSB should have good space to store enough quantities of seeds (and grains) in order to satisfy community demands. Exhibitions stands for seeds do not need much space, neither the office space. Farmers may need an exterior space to meet in big groups, but the community itself can work this out later.

8.3 . CSB Associated costs

Fixed costs of establishing a pilot CSB in Somaliland is approximately are NOK360,500. However, part of the establishment of the CSB demands a lot of variable costs at the beginning, in order to create know-how among partners (capacity building is needed) and to create the seed capital at community level. Follow -up and monitoring of CSB in Somaliland will demand a commitment from partner organizations, which goes beyond DF programme terms. Partner’s organizations understand this challenge and are willing to work on the sustainability of CSB in Somaliland. Therefore, capacity building is needed for partners and selected farmers in the beginning.

- Where to pilot CSB in Somaliland?

The answer is simple: all communities should start implementing CSB as good seed security strategy. As shown in previous sessions, the need of increasing diversity of local landraces, as well as, securing enough quantities of quality seeds are urgent measurements for all farming communities in Somaliland. However, funds are limited and not all communities can begin implementing CSB; at least not with DF limited funding.

In order to select a possible candidate to piloting CSB in Somaliland, rapid observations about technical capacity of partners, maturity and commitment of farmer cooperatives and women organizations was part of the analysis during focus groups discussions. The knowledge and interest shown by farmer groups during focus groups discussions became one of the main criteria to decide where to start piloting community seed banks. A summary of elements observed during field visits in table 5.

After visiting the communities and discussing with partners, the conclusion is piloting a CSB in the community of Lafta Thinka in 2014. Lafta Thinka is located in Gabiley district, which also has long history into agriculture. The Ministry of Agriculture is planning to open an agricultural research center in Aburiin also located in Gabiley district. This may eventually benefit local farmers linked to CSB and its activities.

The pilot CSB will serve as learning and capacity-building arena for the establishment of new CSB with other partners in new communities in Somaliland. The establishment of CSB in other areas and with other partners will depend on the possibilities for close monitoring from partners´ technical staff, since all groups need organizational strengthening in the coming years to be able to manage the CSB themselves.

- Conclusions and recommendations

- Community seed banks are highly needed in Somaliland, both to strengthen seed security and to break Somali farmers ‘dependency on imported and poor quality seeds. CSB can play an important role in recovering seeds of local landraces and in securing enough quantities of good quality seeds to Somali farmers.

- Piloting CSB in 2014: DF should pilot a CSB in Lafta Thinka village ofGabiley district, with HAVOYOCO as implementing partner. HAVOYOCO has been organizing farmer cooperatives and women associations during the last 3 years in Gabiley district, with DF support. The groups are mature enough to assume the challenge, but they need concrete technical support on seed management in years to come.

- Increase diversity on famer fields: it is urgent to increase diversity of local landraces and varieties of main food crops, as well as, of new drought tolerant varieties. It also important to recover locally adapted varieties of main cash crops. The CSB together with farmers’ willingness to experiment can contribute to this goal.

Capacity building already from 2014: our local partner is HAVOYOCO, but also other DF partner organizations in Somaliland need special capacity building for their field staff regarding community- based seed management. As part of capacity building both exchange visits and training seminars should be provided to DF partners in Somaliland.

Therefore, it is recommended to carry out the following capacity building activities:

- Training seminar on community based agrobiodiversity management for technical staff from Somaliland. If possible, pull resource persons from other places to get a good training: concretely those with good experience working with maize-and sorghum among farmer groups.

- Exchange visit to Ethiopia for technical staff and even farmers: to get to know EOSA´s CSB history and the management of the CSB by local communities in Ethiopia. The exchange should allow partners to establish linkages with special institutions and if possible get donations of drought tolerant varieties of sorghum and pulses.

- Exchange visit to Guatemala: for technical staff in order to know more about maize diversity, and also if possible to get donations of seeds of local landraces of both Curcubitaceas and maize, which may be adaptable to dry areas. This will contribute to increase on-farm diversity and the seed stock of the CSB once some of the varieties become adapted.

Collaboration with Agricultural extension Department in Somaliland and FAO: Agriculture extension services in Somaliland need better knowledge about local seed systems and community-based Biodiversity management. For DF and partners in Somaliland, these are relevant stakeholders to engage in trainings and seminars.

FAO has trained some farmers in Somaliland using farmer field schools approach. The outcomes in the field we could not observe, but partners and DF staff can coordinate a visit with FAO in order to find out if FFS are working in farmer fields in Somaliland. It is also recommended for DF staff and partners to have a closer collaboration and if possible work together on common training materials regarding community- based seed quality management.