Somaliland: Where There Has Been Conflict but No Intervention

The distinction between Somalia and Somaliland is lost on most outsiders, but for the people of Somaliland, who made the decision to separate from Somalia in May 1991, it is both very real and immensely significant. It has meant living in peace for two decades – a peace brokered, implemented and sustained by local people. There has been neither a military intervention to end a conflict nor substantial political, military or economic engagement with the international community, focused as it has been on the mayhem in Somalia.

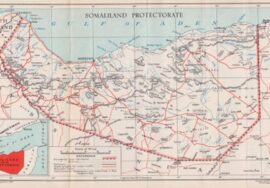

There is a bloody backdrop to the decision to “go it alone.” Somaliland was a British Protectorate until it elected to unite in June 1960, with the Italian colony of Somalia, to form the Northwest region of an independent Republic of Somalia. Unhappy with the union, and frustrated with what appeared to be a policy of neglect, an anti-government rebel movement called the Somali National Movement (SNM) was established abroad to challenge the hardline military regime of Mohamed Siad Barre. The SNM established a rear base in neighboring Ethiopia from which it made incursions into the Northwest and fought a guerrilla war.

The government’s response was swift and unforgiving: civilians suspected of having ties to the SNM faced harsh interrogations, were imprisoned and, in some cases, disappeared. Much of the Northwest became an occupied territory. SNM’s entry into Somalia in May 1988, led to an outright declaration of war against the civilian population in an effort to deprive the SNM of its support and intelligence networks. An intense campaign of aerial bombings in many of the main cities demolished homes, businesses and infrastructure and drove the population out of the country into nearby Ethiopia and further afield. Three years of living in Ethiopia as displaced people, in difficult terrain, took a heavy toll on lives. Many people died of malaria and other health- related causes, and children succumbed because of the lack of clean water.

Exile also politicized people to a point of no return as far as a political future with Somalia was concerned. When Siad Barre was forced out of power in January 1991, the refugees returned home. On 18 May, at a congress in Burao, it was declared that Somaliland had reclaimed the sovereignty it had ceded in June 1960 and was no longer an integral part of Somalia.

For two decades, the pain and struggles of Somalia – the spiral of violence, the absence of an effective central government, the failure of successive interventions and peace negotiations and the grip of extremism – have been the subject of international concern and debate. Somaliland, on the other hand, has remained largely invisible to the outside world. Left to its own devices, it crafted a painstaking, locally-driven peace-building process to resolve a series of internal conflicts and lay the foundation for a system of governance and administration.

It is difficult to pinpoint the political watershed where Somalia crossed the line so as to render a home-grown solution to war and conflict impossible. Although at the time there did not appear to be a choice, Somaliland successfully ended the internal fighting in the early 1990s, nurturing the trust necessary for healing and reconciliation. A collective effort by traditional elders, leading political and civic figures, as well as senior military officers forged, with patience and sensitivity, a meticulous, systematic and comprehensive peace plan responsive to local needs. Political organization, social cohesion and a person’s sense of security and belonging have historically, in the Somali context, come from clan affiliation. When the fault lines in a conflict are defined along clan lines, often among neighbors and even relatives, the violence is personal and deep. “Intimate” violence is much more difficult to resolve than war between strangers. Making peace between people who had previously enjoyed the ties of kinship, marriage and friendship must encompass strategies for over- coming hurt, rekindling trust and creating a sense of common purpose. In a largely pasto- ral society, moreover, where the prospects for avoiding harm and doing well economically are dependent on gaining intelligence from other communities, the notion of peace is shaped by social harmony. The internationally- led search for peace in Somalia has focused on a formula for power sharing; in Somaliland, the emphasis was on the achievement of peace and sharing its benefits.

While Colombians were generous in acknowledging the critical support from the U.S. and EU in their military efforts to eliminate the threat of the FARC, they also spoke at length about the importance of ownership in how a people and a country tackle and resolve conflict in order to mold the society they want to live in. This approach resonates strongly with the people of Somaliland.

In the course of 23 years, Somaliland has worked hard to achieve many important mile- stones. Not only has it enjoyed relative peace, it has also established a functioning system of government, with an executive presidency, an elected parliament, an upper chamber known as the Guurti intended for clan elders and akin to a senate, an array of political parties, as well as an army and police force. Despite its tenu- ous position as a self-declared independent nation, it has held a series of democratic elec- tions since 2003, including two presidential elections, which saw an orderly transfer of power from a sitting President to the head of the main opposition party in 2010. Although criticized for issues related to multiple voting, efficiency and the distribution of state resources, Somaliland was applauded for con- ducting elections that were relatively fair and free of violence.

Though it remains a very poor country, there has been a dramatic increase in eco- nomic growth and reconstruction as well as in revenue generation for the public sector. Private sector and community initiatives were, and still are, the main drivers of the economy. The spirit of entrepreneurship has been a cen- tral and critical thread in transforming the economy. From war-torn rubble, it is now a place where telecommunication, airline, money exchange and construction companies are thriving, including companies which pro- vide electronic money transfers. Private schools, universities and clinics attract an ever- growing clientele and shops and markets offer a wide choice of goods. This is not to say that Somaliland is where it should be: the economy remains precarious, poverty is still widespread and youth unemployment is exceptionally high.

The ultimate goal – international recognition as an independent state – has remained elusive, a fact which remains incomprehensible to the majority of people who are not interested in, or privy to, international debates about statehood and concerns about the wider impact of recognition. What they do under- stand are the practical, tangible consequences of non- statehood: the inability to travel on their passports, the absence of foreign embassies, the impediments to trade and the knowledge that Somaliland remains ineligible for large-scale support from the international community.

Maintaining and deepening peace, as well as strengthening governance, remains a work in progress. In a context of poverty, isolation and non-recognition setbacks are inevitable. Without understating Somaliland’s achievements in the most testing of circumstances, the difficulties of state building remain daunting, especially in a region which continues to be volatile.

To the Colombian military officers and politicians tasked with defeating the FARC reb- els, the definition of the “battlefield” included the economic and social prospects the state offered the people and regions affected by the war. There was an unequivocal understanding that in the eyes of parents who envisioned a better life for their children, jobs, roads, schools and hospitals represented the government, and expressed the quality of its engagement with citizens. It is a lesson the post-independence governments of Somalia ignored at their peril, and one Somaliland would do well to heed.

Outside the main towns of Somaliland, basic services and facilities are scarce and openings for the young remain rare. Much of the population in the rural areas is pastoralist. The livestock they depend on for their livelihood is also the economic backbone of Somaliland; the export of livestock overseas is a major source of foreign currency. Yet successive administrations have failed to successfully invest in pastoral communities. Veterinary ser- vices and drought mitigation efforts, especially the provision of clean water and better range management, can improve the livelihoods of pastoral communities.

Those living in the periphery (rural populations in particular) are all too easy to forget. They are too far away from the capital to be politically visible and too disenfranchised to worry politicians. In Colombia, for far too long, the military and political leaders believed they could afford to contain the threat from the rebels, operating as they did in more remote areas. It was not, we heard, until the “problem” appeared to be getting uncomfortably close to Bogota that it became a matter of vital and immediate national concern, concentrating minds and creating the necessary partnerships to harness all available resources.

This is a lesson Somaliland has yet to apply in the politically tense region of Sool, contested by both Somaliland and Puntland an autonomous region that remains part of Federal Somalia. The creation of a Sool-based separatist movement, which wants to establish a state of “Khatumo” as part of Somalia, has led to a military build-up in both Somaliland and Puntland in 2014 and provoked a war of words. Somaliland’s military has been present in Las Anod, the regional capital of Sool, since 2008. Their visibility as a force needs to be balanced by sustained investment in social services. Much of the money Somaliland spends in the region has been earmarked for political personalities believed to wield influence in the area. There are, of course, likely to be others who can sway public opinion and who feel resentful at being sidelined. Many believe a policy of extending social services in the area − building schools and health centers, strengthening the local Nugaal University and improving access to water and power supplies

– would contribute more to stability. The extent to which the government’s recent initiative to construct a tarmac road in the neighboring region of Sanaag was welcomed, under- lines what officials in Colombia repeated many times; security is important but so is service delivery.

On the streets of Hargeisa, as on the pavements of Cali and Buenaventura, it is difficult to avoid the impression of being in a city of young men with nothing to do and little to look forward to, except perhaps a bleak future. We heard a great deal in Colombia about the interconnections between youth unemployment, the drug trade and the proliferation of criminal gangs.

While the cultural and economic contexts are quite different, high rates of unemployment are also drivers of fragility in Somaliland. The staggering level of unemployment among young men in Somaliland is a daily reminder of what can go wrong. They represent an army- in-waiting for ambitious politicians to use for personal gain and a constituency for disgruntled clan elders to call upon as a political bar- gaining chip and as potential fighters to advance their parochial interests. They are also a ready-made pool of rudderless youth from which militant extremists with an agenda can recruit. Low skill levels and a poor education exacerbate the problem.

Joblessness is not only the absence of financial security and social networks. Going to work exerts its own discipline and brings with it a sense of value for the individual. The emphasis placed by extremists on the urgency and importance of accomplishing a mission contrasts sharply with the sense of drift and weight of time that is the life of too many young men in their prime. It is therefore all too easy for hardliners with extremist ideologies to entice vulnerable youth with talk about fulfilling a religious obligation which will be handsomely rewarded in the after-life. Hopelessness and despair about future prospects for meaningful, productive lives provide a fertile ground for that message to resonate with many young men.

The extent to which the government’s recent initiative to construct a tarmac road in the neighboring region of Sanaag was welcomed, underlines what officials in Colombia repeated many times; security is important but so is service delivery.

An increasing number of youth, both men and women, many of them university graduates, are embarking on a perilous trek overseas in search of work and education. This phenomenon, known as tahrib, usually facilitated by unscrupulous human traffickers, reflects a desperation born, in part, from the belief that opportunities lie elsewhere. Those who have tried to reach Europe by way of Libya or Yemen have become hostages in the conflict-ridden states through which they travel. Families

unable to pay ransoms are forced to borrow money or sell whatever property they have to pay for the release of their children. Failure to do so may well result in their deaths. Despite the harrowing stories broadcast regularly by the BBC Somali Service and Voice of America (VOA), the exodus persists. Seduced by misleading Facebook photos showing a life of affluence and fulfilment in Europe, the documented dangers have not proved to be sufficient deterrents. The frustration of those who come to believe they have been “left behind” means this journey of death will continue unabated. The private sector is the ultimate creator of jobs. This is true in Somaliland as else- where, especially given the narrow base of the public sector in Somaliland. But rising from the ashes of a destructive conflict, with the entire asset base stripped away, private companies had to start from scratch in 1991, with none of the external assistance provided by the international community to other post- conflict economies. Despite the tremendous constraints it faces, visitors to Somaliland are immediately struck by the vibrancy of the private sector, the first sign of which are the ubiquitous metal cages on the sidewalks containing millions of shillings left unguarded. There is no expectation of theft; the clan system is the best intelligence network. The culprit will not only be found but his clan will be held accountable for his actions.

While there are examples of “conflict entrepreneurs” who benefitted from the tur- moil of the early 1990s, it would not be an exaggeration to describe the private sector as the unsung heroes of Somaliland’s struggle for survival. In circumstances which would have discouraged experienced capitalists, businessmen in Somaliland helped establish a rudimentary police force, financed peace conferences, contributed substantially to the government coffers, provided jobs, facilitated remittances and unleashed hope and pride in self-reliance. They imported supplies that made it possible for people to repair their homes and start their own businesses. In the absence of state structures, people turned to the private sector for water, power, transport, schools and healthcare facilities.

The lack of international recognition has inevitably undermined the capacity of the private sector to develop itself in Somaliland. Being invisible translates, in practical terms, to being cut off from international markets. Banks and insurance companies cannot risk engagement outside the rules that apply to other countries. Furthermore, governments do not extend direct budgetary support to minis- tries and most of the assistance given is indirect. It is difficult for any government to demonstrate its legitimacy to its own people when essential services are provided by international organizations, local NGOs and the private sector.

It would be unrealistic to expect local businessmen to finance large-scale and expensive infrastructure projects, such as the port in Berbera, as well as the roads that connect Berbera to landlocked Ethiopia. But without this infrastructure, Somaliland’s economic potential remains untapped, trapping people in an endless cycle of dependence. Over- reliance on the private sector risks excluding the poor, which constitutes a large percentage of the population in Somaliland.

“Fragile” states are inherently those with weak institutions. Somaliland and Somalia’s past shows what can happen when there are no institutions that can withstand the onslaught of war and conflict but that can also assist in providing solutions. Somaliland is now in a political twilight zone: it has gone beyond the point where its nascent institutions can, or should, rely on the resilience of traditional institutions of conflict management, which address problems at the community level.

It was apparent in Colombia that the decision to confront the problem of FARC and other rebel movements brought to the fore- front questions about the state’s responsibility towards its citizens. One of the greatest challenges facing Somaliland is to open up a debate about the nature of the state and the political institutions which can ensure a stable future free of strife. A great deal of time and energy has been spent in forming new political institutions to modernize the body politic without revising the old one. The result is a hybrid system of the old and the new – one which risks diluting the authority of the traditional structures, while failing to fully embrace the new ones intended to lead to democratization.

At the heart of this debate is the future of the Guurti. Instead of remaining a body out- side the political arena with the authority and moral standing to provide an alternative mechanism for dispute resolution, they have become more of an adjunct of the government rather than an asset to the community. Because they are no longer seen as entirely independent, they cannot be relied upon to challenge government policies. The material advantages and proximity to power have proved damaging. Instead of experience and respect within the community as the criteria for nomination, families have come to regard the position as hereditary, leading to a huge inflation of individuals seeking and being bestowed with traditional titles.

The politicization of the role of elders has blurred the lines between the government and those who should be holding the executive in check, and very importantly, between the affairs of the state and the responsibilities of communities. In a context where the state (which lacks funds, human resources and adequate infrastructure to maintain peace) must rely on elders to contain violence and address underlying problems, the confusion and dilution of roles is a cause of concern in Somaliland given the ever-present shadow of conflict.

Instead of limiting discussion of contentious clan issues to competent institutions, namely the Guurti, political elites are using clan politics to advance their own aims, irrespective of its relevance and whether they have been mandated to speak on their behalf. Although political parties are mixed, the arithmetic of electoral politics is based on clan considerations. By maintaining the divisive issue of clan identity at the forefront of public discussions, Somaliland is holding back its political evolution and social integration. It is also slowing down the pace at which respect for the rule of law becomes the foundation for public life, making it unnecessary to look to clan identity for protection.

The overlap between “clanism” and governance can have serious implications for entry into, and dismissal from, the civil service, in the award of contracts, in the independence and effectiveness of the judiciary and in many other aspects of public life. It is difficult for the notion of a civil service based on merit to take root if candidates can too easily rely on the influence of their elders. But without the ability to develop technical expertise and experienced managers, Somaliland’s ability to develop will be stymied.

The extent to which many current conflicts in Africa and elsewhere owe their origin to competition over natural resources has been well documented. The discovery and exploitation of natural resources in fragile environments can usher in instability and sharpen inequality. Many African countries have paid a heavy price for what has come to be known as the “curse of oil.” The recent commercial talks between Somaliland and a number of foreign companies over oil concessions highlight the importance of ensuring Somaliland does not find itself choosing between peace and the lure of uncertain prosperity.

The decision by one company to pull out of Somaliland, citing threats of insecurity as a result of local reaction to the deal, illustrates the political and social minefield, and the security concerns, oil exploration represents. This is further complicated by the existence of prospective wells in the eastern part of Somaliland to which Puntland also lays claim and where it too has awarded concessions.

In May 2014, the Somaliland government announced its intention to establish a 580- strong force named the Oil Protection Unit (OPU), which it said will protect oil companies from terrorist attacks since al-Shabaab elements use the mountains which straddle Somaliland and Puntland. Although the OPU will, according to the government, be under the control of and accountable to the government, the response to the proposed deployment of troops has been mixed. Critics worry about a wide range of implications surrounding the oil concessions, given the fact that Somaliland lacks the wherewithal to negotiate equitable deals. They question the potential for destabilization, the use of oil resources and the security risks associated with the OPU. It would be shortsighted to urge Somaliland to abandon all ambitions related to oil exploration. A thoughtful strategy based on consultations with affected parties and a transparent and clear framework is necessary if the hard- won stability is to be preserved.

To defeat the rebels who finance the war through narcotics, Colombia must work closely with its neighbors; regional collaboration, the only bulwark against fluid borders, is a prerequisite in the war on the drug trade. The parallels in Somaliland’s efforts to shield itself from the murderous activities of al-Shabaab in Somalia, and beyond, are striking. The long and porous borders with Somalia, Djibouti and Ethiopia, and the cross-border nature of al-Shabaab’s operations dictate a policy of cooperation with neighbors.

After more than twenty years of waiting for international recognition, the feeling of being a voiceless people, of not belonging to the community of nations, has left an indelible mark on the national psyche. The all-pervasive aspiration for recognition has come to occupy a dominant and permanent position in political discourse, to the detriment of Somaliland.

Visitors often say they intend to become ambassadors for Somaliland when they return to their countries. Many of us who visited Colombia in June 2014, left with the same determination. We were surprised at how different the country is from popular perceptions. We were impressed by the achievements in security, peace and development, and the commitment and thoughtfulness of those we met to transform their country.

By RAKIYA OMAAR AND SAEED MOHAMOUD