The Somaliland Frankincense superpower

Introduction: Research need and case choice

Sustainably harvesting and sourcing natural products from plants (phytochemi- cals) for cosmetic use has been an important part of the fair trade movement going back to the establishment of The Body Shop by the late entrepreneur Anita Roddick almost 40 years ago (Dennis et al, 1998). Although there has been con- siderable scholarship on fair trade and also detailed management studies of com- panies such as The Body Shop, the particular salience of phytochemical supply chains as development tools has not been previously examined. Our research aims to show that the niche phytochemical sectors can provide an important op- portunity for states with minimal infrastructure to advance even in the absence of large foreign direct investment or aid programs.

Phytochemicals provide a particularly promising area for developing an environ- mentally and economically sustainable development path, since they are derived from naturally renewable materials while fetching high prices with appropriate branding. There is also the potential to vertically integrate the sector from ingre- dients to consumer end-product with relatively low infrastructure investment, par- ticularly with cosmetics that use phytochemicals. Thus, a phytochemical industry which starts from sourcing plants for extraction of the needed compounds can quickly advance to also manufacturing creams and lotions, with far greater speed and less external investment reliance than heavy manufacturing sectors.

For least developed countries (LDCs), this sector holds much promise but making such a sector work effectively requires a keen understanding of ecological con- straints, coupled with detailed process analysis of supply chains in an informal economy. To consider such a prospect, we focused on the case the frankincense resin derived from trees in the Horn of Africa. This resin has broad name recogni- tion globally with multiple uses in cosmetics and emerging uses in pharmaceuti- cals and thus provides an important species to analyze in terms of supply chain dynamics. Of particular interest to us as a source of this resign was the emerging de facto state of Somaliland that presented us with several key attributes that provide for clear analysis as follows:

1. Frankincense resin in Somaliland has characteristics which make it particularly valuable and “brand-able” as compared to other species. Ecologically, it is hard to cultivate Somali frankincense in other locales and hence the establishing a robust supply chain is higher, thus also providing greater opportunity to study this sector longitudinally from its inception (current status) to its development as demand grows and the region develops and diversifies its economy.

2. Since Somaliland is not officially recognized as a separate country by the United Nations, it does not receive major foreign aid. Thus our analysis could focus on the supply chain resilience in the absence of aid programs as a ‘worst case scenario’ of developing such a sector. However, it may also be argued that the noninterfer- ence of foreign donors provides advantages as well for governance development without dependence and can thus be instructive as well (Kaplan 2008).

3. The Somali diaspora’s role in facilitating supply access from their land of origin is an example of how the “remittance economies” that have characterized foreign

workers are being transformed. Not only is money being sent to sustain families in the homeland by migrants but business enterprises that provide win-win outcomes are emerging that can provide for more resilient “North-South” connections.

Background on Somaliland and Frankincense

Somaliland is a small “country” with an enormous impact on the political landscape of the Horn of Africa and beyond. Its history is full of transitions and alternations by colonization and the cold war with the greater boundaries of Somalia reshaped again and again. Today its status is a so-called “break away republic” from Somalia but that is not how the Somalilanders see it. However, Somaliland lacks recogni- tion as a country from the African Union or any other international body. Without first gaining this recognition, it lacks the ability to join the United Nations or partici- pate in the world political stage. This cascades into a list of international opportuni- ties it is ineligible for.

Yet in the midst of tremendous political uncertainty this country has made no- ticeable gains in reducing terrorism and creating stability within an active combat zone. This accomplishment should not go unnoticed by the international devel- opment community and policy makers. Foreign Policy magazine designated it a Green Zone in 2010. One of only three places in the world able to accomplish a degree of stability in the midst of – severe poverty, drought, famine, food aid con- flicts, terrorism by Al Shabaab, the contagion effect, limited military – all with virtu- ally no government operating budget.

Frankincense has been a valued commodity for trade since ancient times by the Egyptians, the Assyrians, the Persians, the Macedonians, and the Kushites. These resins comprise what is believed to be the oldest global supply chain. The Nabataeans, an Arabian tribe, monopolized the trade nearly two thousand years ago and maintained their lucrative competitive advantage for more than 5 centu- ries (Hull 2008 p.275). The northern coast of Somaliland derived its importance from this ancient trade. In fact in Pliny’s book XII of Natural History he devotes much discussion to Frankincense. However, the African link in the production of the resin has been obscured since ancient times: “The chief products of Arabia are Frankincense and Myrrh; the latter it shares with the Cave–dwellers Country but no country besides Arabia produces frankincense.” (Pliny BC p37) Today we know this to be false but this misconception was in part due to the racists sentiments of the times about Africans and the secrecy around the location nd the appearance of the trees.

Even in Pliny’s time the pressure on the trees to produce was of concern “it used to be the custom, when there were fewer opportunities of selling Frankincense to gather it only once a year but at present day trade introduces a second harvest.” Pliny goes on to state “I find it recorded that one of these lumps (of resin) used to be a whole handful, in the days when men’s eagerness to pluck them was less greedy and they were allowed to form more slowly.” (Pliny p45) The ancient uses

of Frankincense (some continue today) included embalming, fumigating, making perfume, sacred religious uses and in traditional medicines including Chinese and Ayurveda.

In modern times potential uses have taken on a new importance in Western medicine. Anti-inflammatory and anti-carcinogenic properties of boswellic acid in frankincense have been noted in both animal and human trials (Efferth et al, 2011). Additional research at the University of Oklahoma concluded: “frankincense oil appears to distinguish cancerous from normal bladder cells and suppress cancer cell viability. Microarray and bioinformatics analysis proposed multiple pathways that can be activated by Frankincense oil to induce bladder cancer cell death. Frankincense oil might represent an alternative intravesical agent for bladder cancer treatment.” (Frank et al 2009)

These resins whether burned as incense, used as essential oil, or in medical trials to cure cancer certainly have a prominent place in the Somali culture and economy. After livestock, these resins are the second most important source of foreign exchange through exports for Somaliland. Before the collapse of the gov- ernment of Somalia officials estimated that 10,000 families were primarily depen- dent on gathering the resins (Farah 1994 p3).

There are two types of Boswellia that grow in Somaliland. Boswellia sacra (sny B. carterii) with the Somali name moxor, which yields a resin locally called beeyo. The second is Boswellia frereana with the Somali name, yagcar, which yields resin locally called meydi. B. frereana is an endemic species found only in the Somali Frankincense region. The Myrrh trees by contrast grow more widespread, mainly in dry inland areas. Apart from Somaliland (and Saudi Arabia where small quanti- ties are produced mainly for domestic use), Ethiopia, Sudan and India rank as im- portant resin producers. However these resins are comparatively of inferior quality frankincense (Frank 1994 p6).

The harvest of Frankincense is done by making a number of precise incisions into the bark and letting the resin ooze out and solidify over a number of weeks. Then the harvesters return to each tree to collect the resin. This procedure is repeated from two to three times over the 5 month harvesting season.

Today the trade of resins has been documented by photojournalists with images of camels carrying sacks to the red sea for shipment to the Middle East and beyond. These idyllic images stir sentiments of being connected to an ancient and sacred process, however this trade has stood still in time to the disadvantage of Somaliland harvesters, while the world it supplies has modernized. The implications for this include the harvesters of the raw resin are left at the bottom of the industry, discon- nected from the profits gained by more powerful Somali and Arab middlemen and end product producers outside of Somaliland. This scenario is not new to Africa and it is certainly a form of Neocolonialism.

Most importantly, this paradigm does not benefit the sustainable economic development of Somaliland. In fact it works to erode gains by not helping to secure basic quality of life for harvesting communities resisting terrorism and food inse- curity violence. These are the very people who are serving as ”homeland security” and allowing for the latest democratically elected government in Hargeisa to move forward. Moreover it erodes the human, social and natural capital the region has built through thousands of years of experience in the resin trade and is loosing its competitive advantage from a lack of ability to raise itself up to the international playing field and protect its industry internally and externally.

This case study seeks to find from the source, the harvesting communities, what they need to improve their livelihoods and if socially responsible business can increase economic development at the community level, and in turn support peace efforts. This information is vital to decision makers, practitioners and stakeholders to gain insight into the Somaliland resin trade.

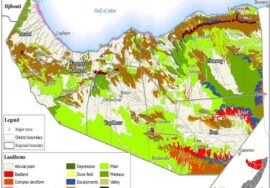

The Sanaag Region

The majority of Somaliland’s Frankincense and Myrrh trees grow in the Sanaag region, in the Cal Madow Mountains in the northern part of the country. Extending from the northwest city of Erigavo (the main hub for gathering, sorting, and storing resins) to several kilometers west of the city of Bossao, it features Somalia’s highest peak Shimbris, which sits at an elevation of about 2,416 meters (7,927 ft).

The dense mountain forest sits at an altitude of between 700–800 m above sea level, and has a mean annual rainfall of 750–850 mm. In addition to rainfall, Cal Madow receives additional precipitation in the form of fog and winter rains, which sustain isolated forests. During the International Union of Conservation Scientists (IUCN) 1995 assessment of flora and fauna of this region it found that Cal Madow has approximately 1,000 plant species, 200 of which are only found in this mountain range (IUCN 1998).

Methods

Field Methods

Drawing from Robert Chambers (1992) models to enable local people to share, enhance, and analyze their knowledge of life conditions, to plan and to act, a participatory rapid appraisal was conducted. The appraisal was conducted in Somaliland on the Frankincense Industry over the course of 6 weeks. This meth-

was influenced by the work of Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) where the poor and exploited people (of which the resin harvesters and sorters most certainly are) can and should be able to conduct their own analysis of their own reality. Outsiders have a role as conveners, catalysts, and facilitators. The rapid appraisal was comprised of a field visit to conduct participatory semi- structured interviews and direct observations in the remote frankincense-growing region in the Cal Madow and the collection and sorting hub in the town of Erigavo (this region is off limits to international organizations and our research team was granted access due to our collaboration with Burao University).

With an agreed upon shared goal of making policy recommendations to govern- ment, donors, and business investors active in the region based on input from the harvesters and key informants, this rapid appraisal constituted the “problem structuring” phase of the policy making process. Inherent in policy analysis are the values of the researcher “shaping the myriad unrecognized practical judgments that go into analytical work.” (Wagenaar 2011 p5) Thus these values should be openly shared. In this case the two main values possessed are the Frankincense (Boswellia carterii and Boswellia frereana) trees are valuable and should be pro- tected and a more equitable livelihood for the harvesters and sorters is more fair and sustainable.

This bottom up rapid appraisal (RA) was specifically focused to use qualitative social science approaches that provide the critical input into making policy recom- mendations. Drawing from the works of Hendrick Wagenaar (2011) this research was conducted in a participatory fashion to obtain the voices of the underrep- resented. “We need methods that allow us to record and analyze the original language in which people express their feelings, beliefs, ideals, fears and desires in relation to themselves, their neighborhood, their community or the impact of a public policy” (Wagenaar, 2011 p3.). Qualitative methods can get to the core of peoples perceptions and the role of the researcher is to match methods with the questions at hand. Moreover, as Wagennar (p.75) states in relation to interpretive policy analysis “Perhaps the most important contribution of qualitative research in public policy is to bring the perspective of the target audience into view. Building upon its ability to articulate subjective meaning qualitative policy research can give voice to otherwise excluded and marginalized groups.” This is not only to make the process more democratic but to identify everyday on the ground knowledge that can dramatically improve development success. Moreover, this RA is part of an ongoing learning process, which continues beyond this RA, for all participants in which the core belief is that “development assistance programs must be part of a learning process opposed to a bureaucratically mandated blue print design” (Korten 1980 p.480).

In this case to understand the state of the Frankincense industry from the per- spective of the harvesters could only be obtained by talking with them directly. Moreover, the interviews with the harvesters and sorters were carefully done to eliminate as much as possible the effect on their answers of having a foreign- er present alongside Somali students from Burao and a local English-speaking

faculty member. Our team was clearly introduced as working to understand the supply chain and not an NGO worker giving aid nor did we have any government or international donor affiliation. The goal was to understand the supply chain and look for recommendations to help the harvesters through established businesses. The veracity of our data collected was highly dependent on the trust established through attention to detail regarding how we were perceived. As honestly stated by one of the landowning harvesters “we are tired of having pictures taken of us, all we want is a fair price for our resin.” These challenges were only addressed by using an adaptable learning process, being flexible, improvising, being relaxed/ unimposing, and with continuous conscious exploration (Chambers 1992).

Our team also traveled to the city of Burao to triangulate and maximize the diversity of information (Chambers 1992) by working with agriculture and business students and faculty of the University of Burao and then to the capital city of Hargeisa to interview the Minister of Labor and the Somaliland Organic Certification Program as well as several Cabinet Ministers.

Semi-Structured Focus Groups and Interviews

During the rapid appraisal one on one interviews and focus groups were con- ducted with the people involved in the industry. The key stakeholder groups were comprised of the harvesters and sorters of Frankincense. Key informants included government officials, the organic growers association certifying Frankincense, and Socially Responsible business owners. Figure 2 represents the stakeholder map for the frankincense supply chain in this region.

The interview/focus group questions were designed after an extensive search of the sparsely available research on Somaliland, Frankincense, and the harvest- ing communities. As well as numerous information sessions with USA-based Frankincense importer, Boswellness, to determine what they already knew about the industry and where knowledge gaps were. The questions were designed for the harvesters and sorters who are the most difficult groups to reach, are the most un- derrepresented and vulnerable, and from a Participatory Development Paradigm are the most important and directly impacted link (after the trees themselves) in the Frankincense supply chain. These questions were identified as key to understand- ing the relationship between the supply chain of Frankincense, the state of people’s livelihoods, and the health of the trees, as perceived by the harvesters and sorters. Moreover, they are also a segment of the everyday citizens on the front lines of re- sisting Al-Shabaab terrorist activities from Somalia in Somaliland. Moreover, since the format was participatory, much discussion expanding or outside of the semi structured questions came up and were encouraged. This was another method employed to ensure the structure was not driving the outcome.

The questions included:

a) Have your harvesting practices changed with the political situation? Specifically have your harvesting/sale practices changed during the dictatorship, since its fall to the present?

b) Do you only harvest and sell frankincense? If no what are your other economic activities?

c) What is the selling price for x quantity of Frankincense? How much quantity do you harvest annually, or other relevant block of time?

d) If you had the choice would like to sell your Frankincense for money or do you like to barter or do you prefer a mix?

e) Who harvests, who sorts, who sells or barters the product?

f) Is the fact that Boswellness is paying you a higher rate for your Frankincense af- fecting your harvesting/sorting practices? Has it affected your quality of life? What is the difference selling to other buyers (other than Boswellness)? (I will try and quantify any identified differences in selling to Boswellness than to traditional middlemen. For example, fewer working hours, less harvesting stress on the trees).

g) How is the health of the trees you harvest? Do you think the trees are in danger? Is there a limit to how much you can harvest from them? (Sustainable Business would need a cap because once you pay more they may just harvest more and kill the trees. If there is a limit how do we offset to respect that limit.)

h) What kind of organizational structure do you have for the frankincense trade in your community or between communities? Is it adequate or would you design something different?

i) How does your new organic certification effect you as harvesters/sorters?

j) How’s life? Are you happy? Are you meeting basic needs? Are your children going to school?

k) What kinds investments would enable you to work more efficiently and/or increase your quality of life?

Coding of Focus Groups and Interviews

Taped interviews were translated and transcribed. First, stand-alone coding was done of the transcriptions according to the questions (a-k above) that were designed for the semi-structured interviews and FG. This was done to get a better understanding of the context and relationships between the questions asked.

Secondly, the interviews/FG’s were analyzed based on the Qualitative Content Analysis (Mayring 2000). Which essentially provides a framework for doing analysis deductively and then inductively. In the first round of coding a deductive category development was used. In this way I went thought the interviews/FG and allow the topics to come out on their own, not using my own ideas and research agenda. (Participatory observation/direct observation (Woodbrindge, case study research). After the deductive round of coding was complete 7 main themes were extracted and used for a second round of inductive coding.

After a third round of coding and specifications on the codes a theoretical satura- tion (no new codes and everything coded, don’t have the feeling that anything is missing was reached. This is the point where no new codes emerge, everything is coded and nothing seems to be missing from the analysis. The analyses (code matrix charts) will show the relations between the codes and the frequencies the codes were used by the different stakeholders. The analysis was conducted using MaxQDA software.

Moreover, the coding was extracted from direct observations in the field and based

Results and Discussion

The Supply Chain

Determining the make-up of the frankincense supply chain was one of the objec- tives of the rapid appraisal. Based on these findings Figure 3 shows the dominant model of the current supply chain. Historical evidence shows that this has been the dominant model since the 1800’s. Where Somali resin is sold to a middleman for extremely low prices then sent to the Middle East, where it is then sold for a higher price in the international market.

This exploitation by the Arab middlemen is attributed to their intimate knowledge of the resins, their close proximity to Somaliland, the inability of Somali’s to reach external markets themselves, and the fragile state of the resins which require pro- tection from heat and moisture. The exploitation of the Somali did not go unnoticed by the colonizers and subsequent Somali government, whom themselves tried to intervene by setting up cooperatives during the 1900’s which failed. Among many reasons cited for the failed attempts to develop an effective enterprise in the sector is the exploitation of Frankincense collectors by their local kin merchants. Prior failures to strengthen the sector caused the Siyaad Barre regime to put the sector

under government control of the Frankincense and Gums Development and Sales Agency until the government collapsed in 1991 (Farrah 1991 pp13).

Thus with a gap in knowledge of the sector since the collapse of the government in 1991, the interviews and focus groups with the harvesters and sorters started with Question A: Have your harvesting practices changed with the political situation? Specifically have your harvesting/sale practices changed during the dictatorship, since its fall to the present?

The answers were unexpected; participants indicated that during the Barre gov- ernment they were receiving a much higher selling price for their resins then today. They were only allowed to sell to the government but the higher price enabled them to make a better living. They also reported that the government provided security for the trees against illegal harvesting and supplied needed advances of food products to take with them when they are in the remote harvesting regions. As stated by a harvester: “The health of the trees now is not the best thing. It is not the best because there are a lot of thieves who are cutting and doing damage. By the way, if it continues as it is, then maybe we could lose them in a short time.” Furthermore in the absence of a government that is able to strengthen the sector, they stated they can do it themselves if a fair price is paid for the resin: “When the price becomes higher, then we have the possibility to protect our own trees by hiring guards. Because then we have the money.”

Thus the major findings related to the current supply chain obtained from coding by question, direct quotes from the focus groups/interviews, direct observation, and key informants are as follows:

• During the time of the Siyaad Barre government the frankincense industry was highly regulated. The product could only be sold to government buyers, thus sus- taining an appropriate price per kilo. The price at that time was reported to be about $50 per kilo for the highest grade of B. frereana. The government also supplied other forms of support such as advances of food for harvesters and protection for the trees.

• Today the situation is entirely different. Harvesters sell their product to any buyer with whom they have the opportunity, often underbidding each other in a desper- ate attempt to sell their resin, thus driving the prices even lower. Current reported selling prices range from $2 to $10 per kilo.

• The people involved in this industry are trapped in a situation with little chance to gain and sometimes not even break even after an harvesting season. Rising food prices, inflated currency, drought attributed to climate change, and scarce oppor- tunities for other jobs exacerbate this difficult situation. Moreover, once the resin enters the Middle Eastern market, it is sold for $25-$50 per kilo. After distillation into essential oil a 1oz bottle (obtained from < 1 kg of resin) can fetch upwards of $70 in the West.

• The economic situation is having a devastating effect on the trees themselves and, subsequently, the long-term sustainability of the resin market. Illegal harvesting is rampant. Youth with few opportunities are reported to sneak into these remote areas during the harvesting season and take the resin before the legitimate har- vesters reach it.

• Even worse for the trees, illegal harvesters also collect resin by making addi- tional cuts onto the bark after the 5-month legal harvesting season has ended. Desperate and irresponsible harvesters are reported as making too many cuts on the trees to drain resin as well as cutting in ways that can and does kill the trees. Thus across the interviewees almost everyone reported over harvesting leading to decline of the trees and in some cases pleaded that without intervention the most valuable species could be lost within the decade.

Moreover, lacking government support harvesters indicated that they are now willing and do sell to anyone who offers them the best price. They indicated they do not feel obligated to only sell to kin middlemen and in fact reported that practice has diminished. This is substantiated by the ability of an US based company, Boswellness, which has no kin ties to the harvesters to buy directly from them. This change in practice, which was earlier cited as one of the major reasons the sector improvements failed, signals a significant change in the supply chain.

Quantity of Resins in the Supply Chain

Official statistics are not readily available on the quantity of resins produced annually in Somaliland. There is also a great deal of unofficial trading in the informal economy internationally. The best figures currently available on global trade of Frankincense resin were released by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). FAO estimates world trade in 1987, for Somali Boswellia as: 800 tones of

B. frereana and 200 tones of B. carterii. Thus Somaliland produces approximately 1,000 tons of resin per year. These estimates have not been updated since this time. In fact, during the rapid appraisal World Bank consultants were encountered who were trying to quantify the amounts of resins produced in Somaliland. This was proving to be a frustrating and difficult task for them. Demand for the resins is generally stable with harvesters reporting that all resins are sold out every year.

Final distillation of the major findings from the first round of coding and the concep- tual model of causal dependencies were extracted to do a second round of coding. The major categories confirmed the findings from round one of coding and the causal linkages. Moreover, this drilling down into the data strengthens the basis from which to draw policy recommendations. Figure 4 also shows the strong cor- relations between drought, government transition, no protection for the trees, low income, dying and endangered trees, thieves, and overharvesting.

Sustainable Business, Organic Certification and Investments

Question F was designed to understand the impact of the ecologically and socially branded diaspora company, Boswellness on harvesters. This company has a stated practice of paying a higher price for the resins and working directly with the harvesters. However, at the time of the rapid appraisal the harvesters were waiting for Boswellness to make a larger purchase then the small ones they had been making. Thus monitoring the impact of this companies practice at the time was premature. They were filled with hope that this company would purchase more resin from them and help them out of their desperate financial situations. Since this appraisal larger purchases have been made by Boswellness and future research should certainly monitor the impact.

What was also on the minds of many of the harvesters was the new USDA Organic certification that Boswellness was sponsoring and working to implement with the groups of harvesters it buys from. Amidst the confusion on why there was a need for the certification (they claimed the product was already organic and did not un- derstand that the certification would allow Boswellness to sell the distilled oil at a higher price thus pay them more for the resin) what the implementation did was to form a “cooperative” of organic harvesters. As stated by the Somaliland Organic Organization “once they [harvesters] know that these people [current harvesters in the organic certification group] are getting a higher price for their resins, everyone will want to join that group.” The other distinction that Organic gives to Frankincense is that it is not synthetic. Many of the Frankincense oils on the market are synthetic and thus Organic is a value added distinction that can determine price. Figure 5 summarizes the relationships as a “mind map” between the various stakeholders following our analysis and from which the policy recommendations are derived.

Policy Recommendations

The following proposed actions have the potential to reverse the current unsus- tainable course of the Frankincense industry. The ultimate goal is to improve the quality of life for the people who depend on frankincense for their livelihood while protecting the trees and the supply for the resin’s worldwide use in emerging cancer treatments and other key applications.

1) Outreach and Educational Campaign

The international community is largely unaware of the plight of the frankincense trees and communities. Moreover the harvesters and sorters know very little about the end uses of Frankincense by consumers. This was further illuminated by a harvester who when I gave him a bottle of essential oil distilled in the USA asked, “How did you get my tree in a bottle?” An international educational campaign to cover areas urgently needing to be addressed include:

1. Granting Somalilandits legitimate recognition in the history and culture of Frankincense,

2. the current plight of the harvesting communities and the trees,

3. the need for large scale protection of the imperiled trees (the Horn of Africa is a designated Biodiversity Hotspot),

4. the importance of an informed market that distinguishes between synthetic and organic Frankincense,

5. the promising use of frankincense in cancer research, for example by Virginia Tech and Wake Forest University,

6. and the importance of a harvester cooperative within Somaliland for improved gov- ernance and sustainability as well as empowerment on the value and end uses of Frankincense to the international community.

2) Fair Trade Frankincense

It is a next logical step to work with one of the Fair Trade organizations and have Frankincense become certified. This effort would be simultaneous with the outreach and education campaign and is critical to solidifying the outreach message for con- sumers while protecting the livelihood of the producers. Fair trade Frankincense will help stabilize the price of the resin and inform distributors and consumers on the need for fair prices as a way to sustain the yield of the trees.

3) Sustainable Business Efforts in a Green Zone

Where government is not able, sustainable business efforts can identify market intervention to secure higher payments/quantities of Frankincense and fewer work hours for harvesters with verifiable sustainable practices. In parallel, maintaining lower prices or exclusion for unsustainable gathering. These two steps will help the market move toward sustainability.

Ideally, legal and financial pressure would be placed on wholesalers who are not supporting sustainable management. Ways to improve market efficiency and raise

selling prices for the harvesters in the short term include:

1. Quickly purchasing a large quantity of Frankincense at the current low price to build a stockpile and give a supply shock to wholesalers. This would allow sustainable businesses to revamp the market for the long run and compensate a group of harvesters (in monetary terms and/or via direct aid) to rest trees while setting up a sustainable management program.

2. Identify other wholesalers and a means to contact them to devise price stabilization options.

3. Moving to intercept the Middle Eastern and European markets to exclude bad actor wholesalers.

4. Launch a global awareness campaign to support sustainable wholesalers and sus- tainable purchasing alternatives including labeling good and excluding bad.

Marketing the Somaliland Resin Appropriately

Specializing the market: Thus this ancient medicine may now have new and sig- nificant modern uses. Thus making protection of the trees even more critical. Moreover, the high quality resins produced in Somaliland should be marketed for specific high end uses such as this. http://www.vetmed.vt.edu/research/ceco/ melanoma.asp

4) Management Guidelines for Healthy and Productive Frankincense Trees

A science based plan is needed to gather information for sustainable management requirements to secure healthy Frankincense forests and trees. Experimental plots to study the effects of different frequencies of tapping and tapping procedures based on existing literature, experts at the University of Burao, and local traditional knowledge are needed. Data collection including tree size, health conditions, re- generation, and possibly ring counts. In addition, further research on harvesting rights for landless harvesters, landowners, and holders of mixed rights (such as grazing and harvesting) is needed. This will provide a better understanding of the access rules and their implications for sustainable management. It is expected, for example, that harvesters who own land will have the highest interest in maintaining sustainable yields and excluding “free riders” versus harvesters who do not own land and have less decision-power.

Once a sustainable yield is determined, coordinated efforts to have a “cap” on production is necessary to prevent overharvesting of resins bought at a fair price. Furthermore, development agencies can give Food Aid directly to harvesters as an incentive to rest trees.

5) Training Youth for Tree Health

Equally important will be to establish a sustainability training program for students at the University of Burao and local communities in the harvesting regions. This training will guarantee the expertise in measuring and monitoring tree health is passed on to professors and students at the University of Burao (to train the trainer). Students, professors, and harvester/sorters would be engaged in training youth in tree health at the community level.

Youth who engage in illegal harvesting have been cited as a significant source of tree health decline. Thus it is important to first educate these youth on how over harvesting and illegal harvesting is killing the trees and, second, to train them to monitor tree health to fill protective positions for the trees. This role would be even more important as a fair price is paid for the resin, making it more valuable and potentially giving more incentive to illegal harvesters.

6) Designation of the Frankincense Growing Areas as Protected

The forest areas where frankincense trees grow are historical and lacking in inter- national recognition. Furthermore their ecological significance inside the biodiver- sity hotspot is a call to action for their protection.

In 1998 Boswellia carterii was listed as potentially threatened (by over harvesting) in the Red List, an internationally recognized monitoring system for plant and animal species. The recent Rapid Assessment (appraisal or assessment – should be consistent!) indicates that a reassessment by the Red List specialists would deliver more alarming information on the status of the trees. The IUCN itself cur- rently cites the need to update this the assessment.

The three main forest areas in Somaliland could be designated as “protected areas.” Interestingly, UNESCO has recently designated the Frankincense trade route in Oman as a cultural heritage site. The key is to have recognized desig- nation for these areas to protect and promote these fragile ecosystems and the people depending on them.

In collaboration with the Department of Tourism and Archeology at the Department of Commerce in Somaliland, an archeological assessment of the frankincense region is needed to determine ancient practices and inform the designation of the protected area.

This includes the prehistoric cave paintings at the Laas Gaal site (a complex of caves and rock shelters near the harvesting region) in the protected area so as to preserve this invaluable heritage site and develop archeotourism opportunities.

7) Formation of a Harvesters’ Cooperative

More effective local governance is needed to ensure the trees are not over har- vested, to dissuade outsiders from ‘raiding’ local resources, and to promote effec- tive fair trade. An harvesters’ cooperative will reduce competition and underbidding and increase cooperation on agreed market and sustainability standards. Since several historical attempts have failed a more participatory development approach is needed. The community needs to decide on the structure of the cooperative with facilitation from experts. These findings would facilitate the successful establish- ment of a cooperative on the ground instead of imposing a structure, which has not worked in the past.

This cooperative is the body that can elevate and stabilize the price of Frankincense, oversee the protection of the trees, and promote the well being of the workers. This

cooperative will also interact with the government of Somaliland and will be con- structed to function autonomously over time without outside intervention.

8) Women’s Empowerment

Women sort and clean the Frankincense resin after it has been harvested. Improvements to working conditions for female workers engaged in sorting and cleaning is needed. Currently these women are sitting on concrete floors for 12 hours per day, in low light conditions, slumped over their sorting boards making between 50 cents to a max of $2 per day.

Several improvements to the sorting stations would improve women’s quality of life including solar panels on the sorting stations (since Frankincense should not be exposed to sunlight), tables and chairs, and gloves.

Sorting stations are also an ideal social setting for training women on growing food and women’s health. Reports show women who grow food do not have to work such long hours and can take more time to care for their families.

Conclusion

The frankincense trees of Somaliland are in peril and so are the people who rely on them for their livelihoods. In order to improve the situation and help to support peace and stability a coordinated effort between development agencies, the Somaliland Government, business, academics and stakeholders is necessary. To do nothing would be a loss for humanity and yet to intervene properly the harvest- ers themselves must be consulted and participatory models of involvement imple- mented for success. As development agencies get involved with government they must seek to make improvements across the entire sector in Somaliland so as not to upset the balance of peace within the country. Clearly, business can have a good or bad impact, mainly by paying the harvesters a fair price or not and discour- aging bad actors. As a government official stated “we need a real buyer, people who are serious about protecting the trees and are fair to the sellers, not buyers who only care for themselves thinking only about today.” Making changes to this industry can upset old dynamics thus a thoughtful approach to manage potential conflict is also needed.

More broadly this research shows that plant products and niche economic sectors generated by natural products have an important role to play in development which is often underappreciated. As the momentum builds to lift the least developed regions out of poverty through environmentally and socially sustainable ways phy- tochemicals and their derivative products must be given greater attention.