Water Sector of rural Somaliland

1.1 Problem Identification

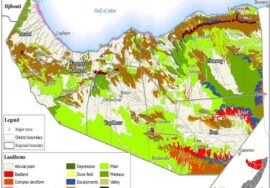

Somaliland is semi-arid. With annual rainfalls less than 250 mm, water has a high priority1. There are no permanent surface water resources and Somaliland is therefore almost entirely dependent on rainwater, with the exception of a few deep wells. Rainfall distribution is bi-modal. It falls mostly in the Gu (mid-April to June) and the Der (October to December) rainy seasons. During the two dry-seasons water supplies are the major limiting factors for human as well as livestock survival. People depend on livestock as their main source of income. This reflects the dependence on the variability of water supply. Berkads are the main water source in many areas of Somaliland. Especially in the Haud region of Togdheer and Galbeet Region, Swiss Groups4 areas of intervention, berkads are the only means of water preservation.

Since 1995, the water project of CARITAS Switzerland has been working in the

Water Sector of rural Somaliland. The main objective of its first activities was to rapidly increase the water availability after the civil war. Rehabilitation of water supply systems was urgent, since many berkads and other water infrastructure had been neglected during the war. Emphasis was given to reconstruction activities and emergency relief. Recent developments have shown that the overall situation is changing rapidly. Private Construction activities of berkads have increased. However, one major hindrance to actual improvements in living conditions is the lack of sufficient expertise and know-how in berkad construction. Extremely poor water quality in rural areas in combination with very low hygiene awareness and little knowledge of the effects of contaminated water cause serious health problems. Furthermore, several problems were discovered during the last project phase, including little cost awareness in construction work; poor quality of structures; weaknesses in community work by the project and the local partner organisations; and the need for an actively implemented hygiene and sanitation component.

.2.1 Historical Developments

Prior to the existence of berkads three water sources were available to satisfy human water needs in Somaliland:

- Rainwater collected in balleys,

- Water collected from togga if available,

- Shallow wells located close to some of the main towns (e.g. Odweyne).

Berkads are privately owned water In particular, within the project region berkads are the main water source. Deep wells can only be found in some of the major towns, such as Hargeisa.

Previously during Jilal people had to migrate long distances in order to find enough water and fodder for their livestock, a typical, environmentally sound, pastoral behaviour, but very laborious. Once water became scarce, herds were moved towards areas with shallow wells or water was brought from these wells by camel. Before the construction of berkads, people especially in the Haud Region mainly owned camels instead of goats and sheep due to their ability to survive without water over a relatively long period of time. Goats and sheep were only kept in areas with a sufficient availability of water, i.e. areas with shallow wells or toggas. For people living in the south of Togdheer Region along the border to Ethiopia this meant that they had to move as far as Odweyne for water. From Gocondhale15 this took up to four days while one camel could carry four traditional water containers (25 litres each). Despite time and transportation constraints this was done at least every two weeks during the dry season. During the rainy season people had to set off about once a month to fetch water.

As a result of berkad construction more and more people have settled down. Migration frequently takes place during the dry season, however, water availability has improved in most areas and people do not have to migrate as far as before. The size of human and livestock populations present in a particular region is influenced primarily by water availability. However, due to increasing water availability the number of herds of goats and sheep has grown. Consequently, overgrazing has become a problem and people migrate more frequently due to fodder than water scarcity. Of course water still is the most important resource for settlement; however, it was pointed out by several interviewees that in a few areas berkads had to be abandoned due to the lack of fodder. Fodder availability is higher in the Haud region than in the northern region of Togdheer. Therefore more and more people move to the South, which in turn results in a higher demand for water.

The first berkads in the region were built in the 1950s when Somaliland was still under British colonial rule. It is said that the idea was first introduced by a person called Xaaxi in 1952, who built the first berkad in Xaaxi near Odweyne17. Most likely the idea was taken from prior examples in Sudan. The following berkads in the region were built in Gudubi and Gocondhale in 1954, and not until 1964 in Haindanleh. A major construction era started.

Construction was continued even after the Italian occupied South and the British protectorate in the North merged and became independent in 1960. More and more people settled down in the Haut region, the demand for water increased tremendously, and as a result, an intense period of construction began. During the 70s for the first time people started to hire contractors to build berkads. It was stated that at the end of the 1970s the border dispute between Somalia and Ethiopia over the Ogaden Region resulted in more and more people coming to settle in the Togdheer Region. This in turn resulted in an increased demand for berkads.

Furthermore, it is said that the Civil War (1988-1991) between the North and the South of Somalia brought constructions to an abrupt halt. After the Somali National Movement launched an offensive in towns such as Hargeisa and Burco, Siad Barre bombarded major towns in the region and more than half a million people fled into Ethiopia. Interviewees claimed that Siad Barre’s army made water sources inaccessible, looted homes and mined the area. However, there is no evidence that supports the claim that a significant number of berkads in the region have been destroyed. After Somaliland declared its independence in May 1991, it was managed to halt internal clan based violence, and since the return of most of the refugees during mid-1990s, construction works resumed. It is important to note that berkads were always privately owned. Over the past four to five years private initiative to build and maintain berkads was significantly influenced and supported by international NGOs.

2.2 The Present Situation

At present most berkads are either not used or in a bad condition. A notably high number of abandoned berkads can still be found today. Many are idle partly due to lack of maintenance during the war, but an exact number is not known. Several explanations were given by interviewees: first of all, after a high percentage of the people had fled the region and not all of them have returned, ownership is uncertain; secondly, returning refugees did not have the financial capabilities to rehabilitate berkads; and finally, people did not own as many herds as before the war, as a result the demand for water decreased, and it was unnecessary to rehabilitate the berkad. However, experience shows that berkad rehabilitation and maintenance techniques are generally appalling and the condition of berkads gradually worsens over time. Effective rehabilitation techniques as used by SwissGroup seem to be too expensive or to be applied directly by the owners.

2.2.1 Berkad Construction Quality

As experience shows, quality of berkad construction changed drastically since the 1950s. Combined effects of war, absence of maintenance during the displacement years, and poor workmanship contributed to the deterioration.

Change in construction quality over time: Barkats construction period

Somaliland’s water resource development projects were almost completely destroyed between 1980 and 1988 due to the Somali government’s actions against its population. The Isaaq genocide in Somaliland began in late 1970, a decade after the supposed unification following Somaliland’s independence from the UK on 26 June 1960. The widespread, slow destruction of Somaliland’s population affected not only Isaaq areas, but also indirectly harmed Awdal, parts of Sanaag, and Darood-populated areas of Sool.

Note the drastic decline in quality during the 1970s. Their motto: build a berkad as fast and as cheap as possible (15 day construction period). This resulted in imprecision, carelessness, and bad quality of construction. Most of the visited berkads observed built during that period are broken today.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENTS AND PRESENT SITUATION

People interviewed gave several explanations for bad quality and a comparison was made between the past and the present.

- Lack of Good Planning and Time-Pressure

At present people are in a hurry: they want to have water as easy and as quickly as possible. Consequently people decide to build a berkad without proper planning and instead hire a contractor. In the past people carefully planned berkad construction and spent a long time on finding an adequate construction sight, on selecting excellent materials, and on choosing skilled masons. An elder from Khatoumo pointed out:

“The problem is not the lack of money but improper planning.”

- Choice of Construction Area

It was said that berkads used to be only up to six or seven feet deep, whereas now they are sixteen to twenty feet deep. This statement claims, the deeper the berkad the faster it cracks. A shallow and wide berkad with the same water volume lasts longer since pressure on the ground surface is less significant

(see graph below). However, the larger surface area results in higher evaporation losses and more difficulties to protect the water against pollution. Therefore, to have a smaller surface area is advisable. Yet, in order to prevent the berkads from cracking a stronger foundation would be needed, which in turn would result in additional expenses and therefore is unrealistic. Swiss Group experience shows that the “deepness”- problem was only true for berkads built in the 1950s and 60s. Since the beginning of the 1970s the deepness of berkads constructed has not changed significantly. The deepness often depends on the underground (rocky, sandy and the possibility to dig) and the financial resources of the owners.

- Insufficient Quality of Materials

Apparently, materials are not chosen as carefully as before. In the past the owner chose the construction materials himself and therefore paid special attention to quality. Today the material is chosen by the contractor, who is not as concerned about quality but rather about profit. For example, in the past good quality sand was brought from Odweyne to mix with the cement – good quality sand with a small percentage of clay. Now sand of a different quality is collected anywhere. The worse the quality of the sand the higher the ratio of cement that needs to be added to the mixture in order to maintain a good mixing ratio. Clay is a problem because it takes in moisture and swells. Cement in turn needs water to set. Therefore the cement cracks if it contains too much clay and not enough water when mixed.

- Lack of Qualified Masons

As pointed out by an old mason interviewed, due to the lack of qualified masons the quality of construction has declined. In his eyes, during the time of British occupation, masons were well trained and did high-quality workmanship. Moreover, most of the skilled masons have migrated to bigger towns to find work and get a higher salary or are simply too old to do the work.

- Lack of Control over Masons

Lack of control over masons and the quality of their work is another difficulty. Supposedly, masons used to be controlled by the owner of the berkad to be constructed. If their work was of bad quality the mason could be held responsible and payment was withheld. At present owners do not take the time to control construction work instead a foreman is hired. A foreman easily finds an agreement with the masons and consequently there is no real control. In case the construction or rehabilitation of a berkad is done by an NGO, the owner usually cannot interfere in construction work.

Nevertheless, masons usually have a reputation and are known to be skilled or unskilled. Yet, if the mason is not from the village nor from the area he does not care about his reputation, wants to finish his job as quickly as possible, and cannot be held responsible later on. It is therefore important to hire masons from the locality.

Furthermore, to define who can be held responsible in case the berkad breaks is easier said than done. Berkads crack due to a) a bad mixture of sand, cement, and water, and b) badly qualified masons. However, masons can only be held responsible with the help of the elders and the clan, even though investment in berkad construction is a sole risk to the owner. In any case a berkad owner never receives full compensation; nevertheless, if accusations are valid he can keep up to 1/3 of the agreed salary. Whether or not a complaint is successful is another question.

- Carelessness

According to elders interviewed, today’s generation has never suffered from severe water shortage and therefore does not remember the times when berkads did not exist. They do not realise what difference a good quality berkad can make to the well being of a family and their livestock otherwise they would pay more attention to sustainability.

“Their life is too easy and they chew chat all the time. They can’t even build or fix their own houses anymore!”

- Lack of Maintenance

Maintenance stands for fixing small cracks regularly before they become

bigger and rehabilitation cost increases. Rehabilitation needs range from fixing numerous cracks to major reconstruction work. Frequent maintenance seems to be difficult due to high prices of material, etc. It is not always understood that through frequent maintenance the berkad lasts longer and in the long run one would spend less on maintenance than on major reconstruction.

2.3 Findings

- A general pattern can be Once water and fodder availability are not in equilibrium anymore a problem is created. The overuse of semi-arid land accelerates the desertification problem. Therefore, it would be important to study the effects water sources and their utilisations have on the environmental surrounding.

- The worse the quality of the sand the more cement you have to use and consequently spend more Contractors ignore that factor and therefore the berkad cracks much sooner. Nobody takes the time to observe the appropriate sand-cement-water ratio. Appropriate curing of mortar with a sufficient amount of water is needed. In hot climates a lot of water needs to be applied during curing over a period of about one week to avoid cracking. People don’t know it, not enough water available, etc. This are only some few point concerning construction quality

- People do not pay enough attention to material and construction quality and do not plan What counts: as much water in as short a time as possible. The future is not taken into consideration.

- No quality awareness

CHAPTER 3: Ownership and use of Berkads

3.1 Ownership

Berkads are privately owned and they serve both human and livestock water needs. One berkad is usually owned by a family and managed by the head of family. Ownership, management, and responsibility for the berkad are passed on to the eldest son. On average a family owns one berkad, maybe two in the extended family. However, it is not quite clear what is meant with “extended family” and how far family members are spread out. It would be helpful for future work to clarify this information. There are only very few, almost none, publicly owned berkads. People who do not own a berkad either use a berkad owned by a family member or one of their relatives or friends. Depending on their degree of relationship or their socio-economic status it is decided whether and how much has to be paid for water.

The actual importance of the owner was confirmed during observations made in the field. One berkad desperately needed rehabilitation. In response to our question why it was not rehabilitated the users respond that the owner was absent and no one else had the authority to make the decision to rehabilitate the berkad. In principle, the sense of ownership should guarantee for maintenance.

3.1.1 Ownership Responsibilities

The berkad owner has several responsibilities, including the management of water usage, maintenance, and rehabilitation.

- He pays for the construction of the berkad and oversees ongoing construction work. It is should be in his interest but, often lack of knowledge about what is good quality to make sure the workmanship is of good Future users (family, friends, etc.) are not obliged to make a contribution; however, most make a contribution according to their abilities.

- The owner rehabilitates the berkad when Again, the users are not obliged to contribute to the rehabilitation, however, contribute what they can afford.

- He is responsible for maintenance and should keeps the berkad in a good condition (fencing, covering, )

- Before the next rain comes the berkad should be is emptied and

- He makes the decisions on who can use the berkad, how much water can be used, and decides on the price of the

When asked how, one of the interviewees explained that in general people know people and how much they can afford to pay. If people come from another area mistakes are made, but can be corrected later on.

- The owner makes a plan of water consumption for the dry

3.1.2 Plan of Water Consumption

Through some interviews it became clear that during the dry season the owner makes a plan of water consumption for the coming months and whether the water available is sufficient. The following factors are taken into consideration:

- The total water consumption per family per month is calculated, including human water consumption (drinking water, and water for domestic use) and livestock water

E.g. Number of families using a berkad, average size of a family being seven persons, is a round twelve permanently and up twice as many in the dry season. However, this varies depending on the size of the berkad and its water volume and the total water consumption of a family including their livestock. For example, one family owns on average 70 goats and sheep and around five camels in the villages visited. The average water consumption of a goat/sheep is 4-7 litres per week, that of a camel about 30 litres every ten days. 70 goats and sheep would drink about 490 litres (2 ½ barrels) per week (1 barrel = 200litres). Five camels would need 150 litres every ten days (3/4 barrel). The average water consumption per family (drinking water and water for domestic use) is 1-½ barrels per week. Average total water consumption per family per week would add up to 4 and 3/4 barrels of water.

- Evaporation

A plan is made on how much water each family is allowed to fetch during the dry season and the water is economised.

Hence, the owner has to be informed whenever water is used or sold to somebody other than the regular users (e.g. migrating people and their herds). Once there is water scarcity strong animals are sent away and the remaining water is rationed. Water use is mainly limited to human water consumption and also given to remaining livestock. In some cases the berkad owner limits the amount of people who can use his berkads to his close family such as sons and daughters and their families, siblings, and the wife’s family. Others either have to pay a high price or do not use the water at all. An exception are those who cannot travel (i.e. old and sick people, mothers and their newborn babies) and poor people (who cannot afford high prices and have a low water consumption). Additionally, it is advisable, as villagers said, to think carefully about who is refused to use your water and where they come from. You never know what situation you might have to face in future, which will lead you to ask them for water in return.

However, berkad owners are not all powerful; there are certain rules and regulations that guide the decision-making process. It is almost impossible to deny close family members the access to water, while it is socially unacceptable to reject poor people. For example, in Gocondhale, at times of water scarcity the village committee decides water distribution. As a result nobody can deny a community member access to his or her water source – everyone is obliged to share.

3.2 Use

Each berkad, depending on its size, can provide for eight to twenty families sometimes even up to thirty or more. Whereas the level of water consumption differs from family to family, depending on the size of the family and their livestock. Family members (including extended family) and relatives (the clan) have priority and are the main users of a berkad. Determination of who uses the berkad differs from season to season and depends on whether there is water shortage, how close the users are to the berkad owner, and if they contributed to the building of the berkad. As mentioned in regard to ownership, the only exceptions are the poor. According to a rotating system the elders decide when and for how long the poor in the village use a certain berkad.

During water shortage people migrate to villages where they have family and relatives or friends to use their water. For example, in Qolqol they move to villages such as Gudubi, Abdi Farah, Abdi Dehre, Ismail dheria, Haindanleh, etc. If water is not available, they move further towards areas where other relatives live, such as villages in Ethiopia. In turn when their relatives face water shortage they come to Qolqol26. At the moment most of the people from Haindanleh move to the Gas area and vice versa.

3.3 Payment

There are slight variations from village to village when decisions are made on who has to pay for water, when, and how much. However, a general concept is followed. As mentioned before payment of water depends on the relationship between the berkad owner and the user and the price depends on the season, the availability of water, and on the financial situation of the user. For example, a man from Haindanleh always moves to Ismael-Dheria in case of water shortage and shares the berkad of his cousin without payment.

During rainy season water is generally very cheap or for free. Towards the end of the dry season, around the beginning of March, prices go up and most people have to pay for water (5 -10.000 Somali Shilling per barrel). However, this decision also depends on the individual owner. Prices can differ from region to region but are generally around the same. During dry season, when there is a shortage of water the prices rise and sometimes even family members have to pay for the water. The more people and animals need to be supplied with water the higher the price. The more animals are owned the wealthier the owner and the more he/she can afford to pay for water. People who are not obliged to pay (i.e. family members) usually pay as much as they can afford to pay.

People who come from outside and are not well known by the owner are usually charged for water. However, as one man in Haindanleh said, since the socio- economic situation of strangers is unknown prices are minimised at first. Only after two or three weeks prices will be adjusted to an “appropriate” price. However, this needs further investigation.

In general it seems that the poor are either charged very little or not charged at all. Usually it is the owner’s decision to make whether users have to pay or not, however, interviews in Gocondhale show that elders also discuss and make the final decision on these issues. As mentioned before they determine who is categorised as poor and therefore has the right to get free access to water. To avoid discontent, a system of rotation makes sure they use different berkads and not always the same one. For example, a poor man interviewed in Gocondhale uses the berkads of his friends for free when he needs to. During the rainy season he uses the balley. During the dry season he buys the water from berkad owners. His demand for water is about one barrel per week for domestic use. He can afford to pay 5.000 Somali Shilling per barrel. His livestock is part of another herd owned by his family and he does not have to pay for the water they drink. After all he does not have many goats.

3.4 Emergency Water Supply

Families left behind at times have to buy water from trucks coming from towns such as Hargeisa, Buroa, and Odweyne (10-15,000 Somaliland Shillings per barrel). This is organised by the elders or a special committee elected by the elders. They sit down together and discuss how much water is needed, who can afford to pay and who cannot, what proportion of water is distributed to each family, where to get it from, who will go and buy it, etc. Afterwards they decide which berkad to store the water in and who is responsible for distributing it to the people. The head of each family that needs water pays for the water. If there are some poor people who cannot buy water, elders are informed and ask others to contribute some water and animals. Payment is in cash or animal exchange. Individuals could remember that the last main droughts were in 1974, 1984, 1997, and 2000. Others claimed this only happens about every four years. In 1997 and about two years ago there was a severe drought, water was scarce and needed to be bought from Hargeisa. At that time some organisations such as UNHCR and the Somaliland Government

distributed water. At times of severe water shortage a barrel of water costs 13,000 Somaliland Shilling, whereas the normal price during dry season is about 5, -10,000 Shilling.

3.5 Findings

- The usage of berkads close to the village differs from the usage of berkads far away from the village (clusters). The pressure on the berkads close to the village is much

- The higher the number of berkads, the bigger their size, the bigger the water availability and the more likely it is that poor people do not have to pay for water

- The more animals you have the more you Poor people do not have to pay because their animal water consumption is not very high.

- The price of water would be interesting to see in relation to the general income of people. How big is the percentage of money that needs to be spent on water in relation to income? How big is the average family income per year? This needs to be studied further.

- Furthermore, it could be interesting to find out if, in principle, enough money is earned through water sales to pay for frequent maintenance and rehabilitation.

.

CHAPTER 4 : Construction and rehabilitation

4.1 Introduction

In general, existing berkads are rehabilitated before people decide to construct new ones. Costs are lower and most people claim to be unable to afford building new ones. However, a berkad is seen as very beneficial as it enables independence from other water sources and a profit can be made from selling water to others. Yet, sometimes people start two things at the same time. Rehabilitation works on an old berkad are continued, while construction works on a new one are started. Basic construction works such as e.g. digging can be done without major funds30. Actual construction works start once sufficient finances are available.

The construction process of a berkad is usually divided into four phases

- Planning,

- Digging of a hole,

- Collection of materials and finding skilled labour, and

- Construction

The duration of construction work depends on

- The size of the berkad,

- Good preparations, and

- The financial situation of the

About 6 weeks to three months are needed for the construction of a berkad once the materials are available. According to information given a berkad can cost about 1500 US$ or 3000 US$, depending on its size and the quality of the materials. To give an example, a shop-owner in Khatoumo would have to sell his shop in order to be able to afford a berkad.

4.2 Planning of Construction

The planning and preparatory stage of berkad construction is the most time consuming part of the entire construction process. Most berkads, even if managed by one person, are owned by an extended family due to costs that need to be covered

(i.e. construction, rehabilitation, maintenance). Therefore, the decision to build a berkad is made collectively. This would imply that all heads of the family would have to come together and discuss the matter. This proves difficult since the family can be spread over the whole region and even further. A young man in Khatoumo reasoned that his family would have built a berkad already if it would not have been so difficult to get people together to discuss the matter. Part of the family lives in towns as far as Hargeisa or even Berbera31. In case the berkad owner has enough money himself he can build a berkad on his own accord without consulting the family.

4.3 Financing and Contribution

The owner finances the major part of the construction of a berkad. However, it is in the interest of future users to contribute if they can afford to. First of all the contributors will have priority when it comes to water consumption and will not have to pay for the water. It is more common to make a contribution of labour, material, or pay in animals.

Predominantly family members contribute to the building of a berkad; after all, they will be the core users in future. Even family living in towns or abroad contribute if possible. Nevertheless, if contribution is not given the berkad can still be used against temporary payment. Once payment is seen as sufficient the owner can decide to cancel it. In case a family member was absent or not informed at the time of construction and could not make a contribution later payment is not obligatory.

4.4 Materials

Once constructions can be started the needed materials such as cement, gravel, sand, and stones are bought from Hargeisa, Burao, or Odweyne. Other materials are collected locally. Construction of berkads is especially dependent on availability and prices of materials such as cement and gravel which have to be bought. Gravel is usually difficult to get and cement very expensive cement in Somaliland is

comparatively very cheap 3.5 – 4.5 USD per sac. The collection of materials and preparatory works can take several years (on average 2-3 years).

4.5 Skilled and Unskilled Labour

Unskilled labour usually consists of family members or people from the village who will use the berkad later on. Skilled labour (e.g. masons) needs to be hired which is important to the quality of construction. Skilled labour is hired either form the village or from other villages they know. Usually they only take people they know and can trust. In Haindanleh people mentioned the techniques they learned from Swiss

Group, which they still use (e.g. using the wire mesh for reinforced plastering, several damage prevention methods, use of a Shandoo before the actual berkad).

4.6 Findings

- Financing of berkad construction is usually done by family and future The cost of berkad construction should be seen in relation to the average annual family income.

- Planning and resource mobilisation is the most time consuming part of the actual construction Planning and mobilisation of funds, material, and labour can take up to two years. Whereas actual construction work only takes a few months.

SWISSGROUP INTERVENTION

5.1 Introduction

Once water from communal balleys is used up people in the Haud entirely depend on berkads. People’s use of berkads indicated that peak dependency occurs during the dry season between the “Deir” rains (Oct-Nov) and “Gu” rains (April-June). The focus of the project, implemented by Swiss Group, is on the rehabilitation and construction of berkads and the general improvement in water availability in the Haud area of Togdheer Region. Many people in these rural areas are already investing in the construction of new berkads by themselves. Therefore, in some target communities SwissGroup started to introduce a new promising approach of a ‘100% material contribution’. Whereas berkad owners contributed all necessary materials while the project provided technical expertise and paid skilled labour. The project plans to continue with this approach, since the idea was accepted by a number of beneficiaries. A berkad construction plan can be seen below.

5.2 Who did Swiss Group Reach?

According to information given in the villages, berkads rehabilitated by Swiss Group improved the general water situation tremendously. It was claimed that during the past dry seasons people did not have to bear water shortage. Most of the people reached by the project are people with a middle socio-economic background – meaning, they are neither wealthy nor poor, but range somewhere in the middle. In Gocondhale, for example, two of the berkads rehabilitated are owned by people with herds the size of a bout 100 goats and sheep. The three others belong to people who are considered to be “poor” as they own 15-20 sheep and goats only.

Even though rehabilitated berkads are privately owned they benefit the whole community as explained before. In Gocondhale, the five berkads rehabilitated

allowed a significant increase in the number of families who benefit from the berkad water. Most important, the beneficiaries come from different socio economic backgrounds. The more water is available, the cheaper the water and the more water can be shared with people who cannot afford to pay for the water.

5.3 Al-Salama Construction Work

In general Al-Salama, a local NGO/contractor, construction work was seen as efficient and worthwhile, since the overall situation of the village has improved due to the increase in water supply. However, opinions vary from village to village. A major difference can be seen between villages where rehabilitation work took place in early and in later stages of the project. Construction work improved over time. For instance, general opinion in Haindanleh illustrated that Al-Salama did not seem to be well experienced and workmanship was of poor quality. Al-Salama was criticised for the lack of control of its masons. A good mason needs to supervise his employees constantly in order to ensure good quality of construction. Apparently, Al-Salama did not. Whereas, in most additional villages people agreed that workmanship quality was quite good. The only exception was the opinion that the mix ratio of cement and sand was inappropriate and too little cement was used. However, most of the people interviewed lack the know-how to comment on that.

During Swiss Group intervention by Al-Salama38 owners of berkads rehabilitated sometimes did not do not have the authority to control the ongoing process. When a local mason in Haindanleh gave recommendations, they were simply ignored by the contractor, even though he had the know-how to make constructive suggestions.

As mentioned above promotion and the use of indigenous techniques to improve water quality was successful. Berkads constructed by Swiss Group are covered with shrubs. Experiments during the EC evaluation showed that this technique, just the same as the expensive covering of berkads by roofs made from corrugated iron sheets, has reduced evaporation by 50% in comparison to non-covered berkads39. General opinion showed that new techniques introduced by Swiss Group were seen as very effective and useful (e.g. wire mesh for improved plastering, covering, sedimentation chamber, animal trough). Local masons were able to improve their own construction techniques; special emphasis was given to the wire mash mesh.

5.4 Conclusion

In conclusion, most of the rehabilitated berkads observed are in a good overall condition. The concrete shows only a few cracks. However, the lack of maintenance and especially operation is a problem. Covering, fencing, and animal troughs need frequent maintenance, which currently does not take place. Animal troughs are not always separated from the berkad by fencing and therefore increase the risk of animals getting too close to the water resulting in pollution. Due to sedimentation and pollution (i.e. organic matter, animal faeces, sometimes garbage), resulting in a decline in water quality and the development of algae, frequent cleaning of the berkads is needed but not observed.