Peacebuilding and political rebuilding in Somaliland are homegrown

Somaliland’s story is not one of secession but of reclaiming independence 26th June 1960. After an ill-fated so-called union with Somalia and subsequent oppression, Somaliland fought for and won its freedom in 1991, achieving remarkable stability in a volatile region. This historical account corrects misconceptions and highlights Somaliland’s unique journey.

Although Somaliland faced setbacks from two internal wars (1992 and 1994-96), it has remained one of the most peaceful areas in the Horn of Africa. Clan reconciliation efforts, self-funded and lengthy (early 1990s), resulted in a power-sharing government. Somaliland’s lasting political stability, reconstruction, and development are built on this. Somaliland challenges the belief that Somalis cannot govern themselves. Although Somaliland faces persistent challenges, particularly regarding its democratisation, it offers an alternative model for state-building in the Somali region.

Creating peace and building a country

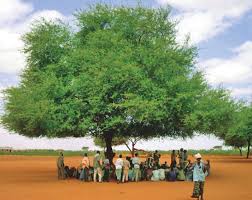

From the start, the presence of effective traditional institutions in Somaliland was essential. These institutions persevered through British protectorate rule and Somalia’s statehood, undergoing transformation but maintaining their functional integrity. The fight against Siyad Barre saw the rise of temporary elder councils (guurtiida) which quickly became makeshift governments. They controlled militias, settled arguments, dispensed justice, worked with international groups, and collected local taxes due to the lack of official local administration.

Furthermore, established clan elders supplied a convenient method for resolving conflicts and a structure for reconciliation. Between 1990 and 1997, no fewer than 38 clan-based peace and reconciliation conferences and meetings led to Somaliland’s cessation of hostilities and lasting stability.

Western and traditional aspects dynamically combine to form the new political system, as it’s often described. Clan-based power sharing and balanced political representation (the beel system) are its foundation. This all unfolds, though, within the context of Western-style processes and governmental bodies, such as elections, parliament, and the cabinet. The core of the system, the powerful Upper House (the constitutional Guurti), ensured traditional and religious elders had a political voice.

The reintegration and demobilisation of ex-combatants proved crucial for neutralising potential troublemakers. Somaliland’s post-1993 gain from controlling the port of Berbera stemmed from the lack of other significant resources that could have fuelled a war economy. Port revenues allowed the government to absorb many militias into a new national army. Previous SNM leaders received cabinet positions. A successful government tactic, cooption worked alongside consensus building.

Seeking international recognition within former British Somaliland strongly motivated stability. The winning SNM and all parties understood that Somaliland’s recognition as an independent state depended on a negotiated settlement of unresolved clan war issues. It was equally obvious that a government required at least basic approval from every clan.

Somaliland’s need to project a modern, democratic image was further understood by the political elite. Although democracy’s introduction offered stability, it also created an inherent contradiction. Because clans remained important, the political system had to incorporate clan power sharing in elections (often through nominations), like with the Guurti.

Stabilization and political reconstruction

Stabilisation and political reconstruction resulted from five major contributing factors:

1.Simultaneously, peacemaking transitioned into state formation and state-building alongside reconciliation and democratisation. While every major clan conference included all these elements, the focus changed subtly with each step, fostering organic growth and practical adaptation as needed.

Unlike many national government formation processes, Somaliland’s process lacked defined timelines and specific goals. Instead, its emphasis has been on internal processes, a focus reinforced by the slow, gradual increase in international aid for strengthening institutions and democracy.

2. Government authority spread slowly eastward from its western bases, encountering resistance from a disaffected clan-based opposition and challenges from nearby Puntland.

Unlike a top-down, prescriptive approach, this gradual and ongoing process has enabled diverse state-building, allowing time and political space for local needs.

3. Post-1993, leadership has been decisive, providing both vision and direction. Late Mohamed Egal, a highly respected former president with a long political career, consolidated power and led Somaliland’s democratisation efforts.

4. While the clan system has hindered state and nation building, it offers crucial checks and balances. Although its capacity has grown, the executive remains pressured to balance the competing interests of various clans and sub-clans, within and beyond the state. This limits the central government’s options in areas that could otherwise destabilise the region.

5. Compromise and consensus-building principles continued to be crucial following Somaliland’s democratisation. Somaliland’s insufficient legal framework, lacking both regulation and flexibility, still allowed for the clan social structure. Stability was achieved through codes of conduct, mutual compromise, and mediated solutions.

Making Somaliland’s political system more inclusive

Although Somaliland has seen successes in state-building, it has also experienced conflict and challenges. Somaliland’s rebuilding was disrupted, and its territorial unity almost destroyed by two civil wars in the 1990s. The irony is that the central government’s strengthening has also had some destabilising consequences. For example, the beel political system’s legitimacy and ability to protect clan interests were increasingly threatened as the executive branch seized more power.

However, the pledge to implement electoral systems following the 1997 Hargeisa reconciliation conference offered a crucial opportunity for change and reform. Despite a five-year delay in adopting a constitution, the democratisation process eased many emerging tensions and dissent.

However, the 2001 transition to a constitutionally based, multi-party democracy introduced new challenges to stability. The central question concerned the successful transition from a politically stable, traditional Beel-System to a citizen-rights-based constitutional democracy.

Somaliland’s deeply rooted clan system necessitated a highly adaptable democracy to overcome strong internal resistance to structural change. Many social and political forces had to be accommodated by political parties, the National Electoral Commission, candidate nomination procedures, the election system, and voter registration processes. This severely limited the capacity to build effective, stable, formal, and professional government institutions.

The multi-party system’s winner-takes-all approach differed from the traditional, more inclusive system of clan representation. Political disagreements have occasionally risked escalating into violent clashes. The private resolution of these disputes has hampered the creation of formal conflict management institutions. Private mediation has not proven to be reliable, efficient, or sustainable.

Weakness persists in the judiciary and the legislature. Even with a constitution, the executive branch is much stronger than the others due to the absence of effective checks and balances. Parliament lacks the constitutional power to oversee the executive. The executive branch is not held accountable by the legislature because of its resource constraints, lack of expertise, internal conflicts, and weak political will. The judiciary is largely subservient to the executive.

Somaliland’s formal systems of governance have been bypassed in several areas, such as security, parliamentary rights, budgeting, and the imprisonment of dissenters. Mismanagement of scarce public funds is common due to rampant patronage.

The electoral process has placed additional strain on Somaliland’s young political system. The first district-level elections happened in December 2002. The constitution now only permits three political parties; those that were most successful in the recent elections. The restrictions and underdeveloped structures and democratic processes within parties severely limit political competition.

In the 2003 presidential elections, the ruling party narrowly defeated the opposition by just 80 votes. A Supreme Court ruling favoured the government after the opposition disputed the election results. The opposition only conceded victory to President Dahir Rayale following intense mediation and significant public pressure.

However, a divided government emerged in 2005 when the opposition secured a parliamentary majority. The nation has been embroiled in recurring political standoffs between its executive and legislative branches ever since.

Meanwhile, the Guurti’s credibility has taken a major hit due to its ties to the executive branch, hindering its constitutional duty to resolve the nation’s political disputes. The ambiguity in existing legal frameworks has rendered them insufficient for resolving these disputes.

Weak formal institutions, power imbalances among contestants, and inherent contradictions between social structures (clans) and constitutional procedures have caused a prolonged delay in the second electoral cycle.

The local elections scheduled for December 2007 have been postponed indefinitely. Originally planned for April 2008, the presidential elections faced yet another postponement in September 2009, marking the fifth delay and leaving the election date unspecified. The postponement of elections has resulted in extended terms for both local and national governing bodies. Instead, the Guurti’s terms of office have been controversially extended on several occasions.

Two years of incremental delays have undermined Somaliland’s emerging democratic system and tarnished its reputation. In the end, mirroring the unfinished political change mentioned earlier, they now risk jeopardising Somaliland’s stability.

Weak domestic support for democratisation is at the root of many of these problems. Somaliland currently lacks a clearly identifiable popular movement driving democratisation.

Civic groups and organisations that bridge clan lines are rare, hindering the development of widespread social movements. Without experience in liberal democracy, people tend to passively await guidance from above. While democracy is widely seen as beneficial, it currently suffers from a lack of active participation.

Somaliland’s unrecognised status and its disputed borders

Somaliland’s stability is most threatened by militants connected to the (allegedly Islamist) insurgency in south-central Somalia. Al Shabaab and like-minded groups are driven underground by their lack of public backing. However, since 2003, they’ve repeatedly assassinated aid workers and carried out three simultaneous suicide bombings in Hargeisa in October 2008. Working against Somaliland’s independence and its secular democratisation, these groups advocate for either Somali unity or a global universalist agenda.

The territorial dispute between Somaliland and Puntland over Sool and Eastern Sanaag remains a persistent issue. Somaliland’s claim rests on its former British independence borders 26th June 1960, unlike Puntland, which asserts its claim based on the presence of the Harti clan communities within the disputed territory.

The conflict stayed a cold war until it erupted into violence in 2002. Following that event, the opposing forces have remained deadlocked, leading to repeated battles. In October 2007, Somaliland troops took control of Las Anod, the capital of Sool. Until the core conflict is addressed and territorial disputes are settled, the tense situation and sporadic clashes will persist.

Somaliland’s pursuit of international recognition and its strained relationship with Somalia significantly contribute to and underpin the external challenges it faces. Somaliland’s patience with the stagnation on these issues is wearing thin. This concern is heightened by the lack of territorial guarantees and protection available to it as an unrecognised territory, despite its relatively close ties and security cooperation with Ethiopia.

Insights gained from Somaliland’s journey

The success of Somaliland’s peacebuilding shows the potential for homegrown solutions, especially considering the Somali context and impressive sustainability.

Somaliland, receiving minimal international aid beyond its large diaspora, achieved remarkable feats including demobilisation, establishing law and order, managing a deregulated economy, drafting a constitution, and starting a pluralistic democracy.

No outside or imposed peace was required for this to happen. The national compromise in Somaliland grew locally, adapting to different regional contexts and avoiding hasty shortcuts often seen in peace processes.

Somaliland’s peacemaking, institution-building, and democratisation, though overlapping, have unfolded sequentially, beginning with a ceasefire, followed by relationship rebuilding, reconciliation, and finally, a locally-driven process shaping the state’s future.

However, Somaliland’s successes are not guaranteed elsewhere. Political rebuilding after a war isn’t straightforward, nor is it guaranteed to last. Persistent efforts to redefine political institutions (e.g., changing roles of traditional leaders), combined with recent democratisation setbacks, emphasise the continuous work and positive circumstances necessary for lasting consolidation in every instance.

Somaliland’s success can be attributed to a unique confluence of factors: a robust traditional system, a lack of resources fuelling conflict, and the pursuit of international recognition.

Somaliland’s lessons learned are consequently not easily applicable elsewhere, especially in Somalia. However, they should strongly promote international practitioners and policymakers backing locally-led peacebuilding and political rebuilding whenever feasible, across national, regional, and local scales.